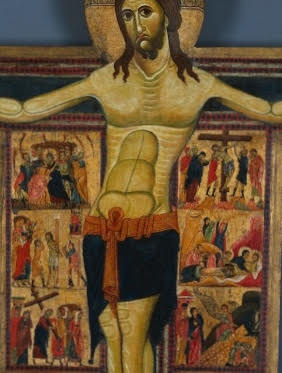

This 13th century crucifixion from Pisa also depicts scenes from Holy Week: Christ’s arrest, his scourging, carrying the Cross, as well as his death, burial, and resurrection. (Cleveland Museum of Art)

Holy Week is the opportunity to celebrate and contemplate the last week of Christ’s ministry, from his entrance into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday to his Resurrection. The heart of Holy Week–the heart of the Christian year–is the nexus of Good Friday-Holy Saturday when Christ’s death and resurrection are celebrated and proclaimed.

Christ’s death was more than a tragic event for a particular person. His death was the encounter between God and Death itself. Once Death had entered the world, following the sin of Adam and Eve, it consumed everything. But when God allowed himself to be consumed by Death, then Death consumed itself. Christ’s resurrection is the pledge that Death has been rendered powerless although it can still be frightening–like a serpent or a chicken with its head cut off, squirming around and spewing blood but harmless apart from whatever fear or disgust we give it.

“Christ concealed the hook under the bait by hiding his strength under weakness. Therefore that murderer who from the beginning thirsted for human blood, rushing blindly upon weakness, encountered strength; he was bitten in the act of biting, transfixed [with nails] as he grasped at the Crucified…. I behold the jaws of the serpent pierced through, so that those who had been swallowed may pass through them…. Well may he be angry, roar, and waste away, for the prey has been snatched from his teeth.” (St. Guerric of Igny, Sermon 30)

In the Middle Ages, many images of Christ on the Cross–especially those based on Byzantine models–contain images of the other events in Holy Week as well.