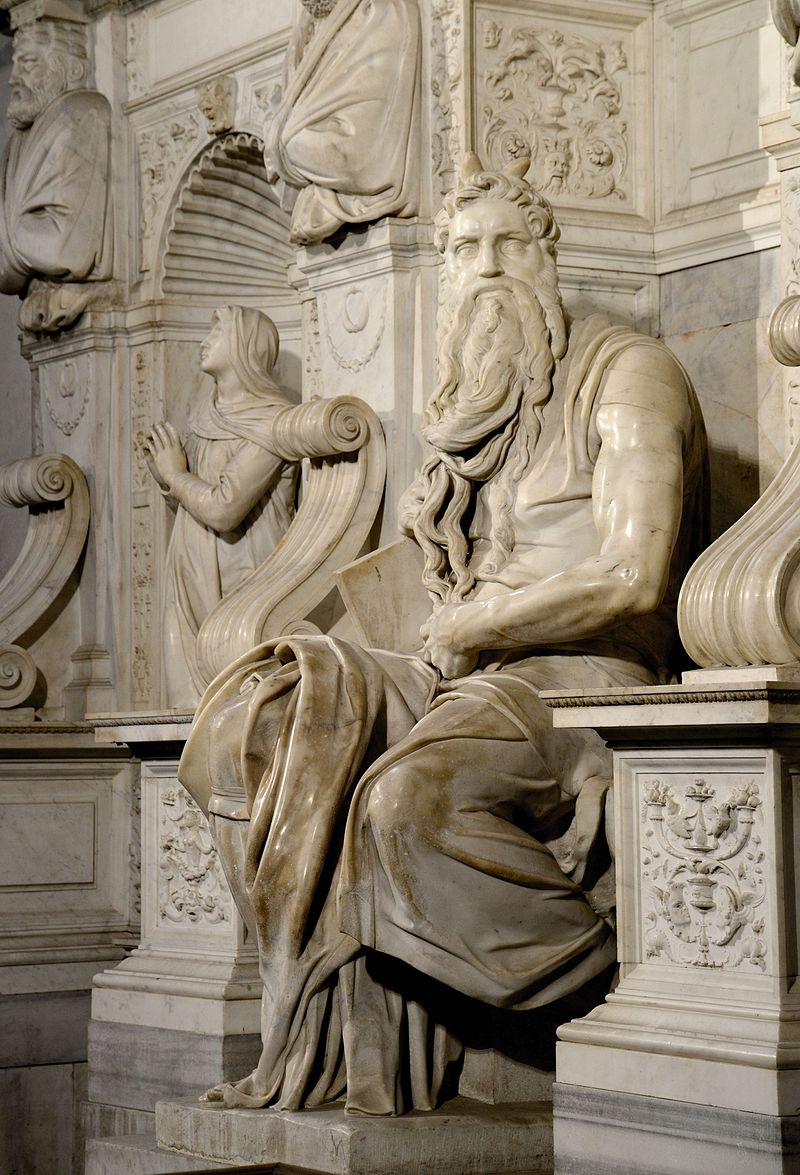

Statue of Moses by Michelangelo, in the church of San Pietro in Vincoli, Rome. The relics of the Maccabees were kept in this same church.

The veneration of the Maccabean martyrs is unique in the Judeo-Christian tradition: they are the only martyrs commemorated by Jews and Christians alike. The seventh chapter of the Second Book of Maccabees (in the Old Testament) tells the story of seven faithful Jewish brothers who maintained their fidelity to the Law of God in the face of persecution during the tyranny of Antiochus IV in the second century B.C. The New Testament book of Hebrews commends these martyrs of Maccabees as exemplars of living faith (Heb 11:35).

These seven Jewish brothers and their mother were arrested and ordered to eat the un-kosher flesh of a pig. The horrific murder of these Maccabean martyrs was so terrible and gruesome that we derived an English word from it—-macabre.

The festival of Hanukkah in December celebrates the revolt led by the Maccabees against the Syrian emperor Antiochus IV. Christians have long commemorated the Maccabees on August 1 and the relics of the 7 Maccabee brothers, with their mother and teacher were long kept in the Church of St. Peter’s Chains (Rome). The relics were sent to Germany to be housed in a church in Cologne (the same city where the relics of the Magi are kept); evidently the Maccabean relics had been kept in Cologne before they had been sent to Rome.

By keeping the Maccabean relics and the statue of Moses in the Church of St. Peter’s Chains, we can see the connection between the Law of Moses and those Maccabean martyrs who died for refusing to abandon that Law. Even more, their memory is joined with the imprisonment and eventual martyrdom of the Apostle Peter. (We know that the festival of Hanukkah was still fairly new in the first century AD but that Jesus celebrated it with the apostles in John 10:22-23.)

You can find a very interesting article (in German!) here about the relics of the Maccabees that includes close-up photos of the golden reliquary which contains their bones. (If you open the page using Chrome, it will offer to translate the page for you–I want to thank my daughter Rebekah for teaching me that trick!)

The reliquary itself is fascinating. It was apparently made in 1500; it is a wooden box in the form of a church, covered with gilded copper plates. The walls of the shrine and top portions are composed of 40 scenes in which the story of the Maccabee brothers and their mother is placed in parallel with the suffering of Christ and His mother Mary. One of the most obvious examples is the contrast of the flagellation of the Maccabee brothers and the flagellation of Jesus. On the front of the shrine is the Coronation of Mary and the Coronation of the Maccabees, while on the back the Ascension of Christ is depicted with the heavenly glorification of the Maccabees.

The shrine for the Maccabees’ relics in St. Andrew’s Church (Cologne, Germany).