St. Apollinaire was a Syrian, elected to be the first bishop of Ravenna (which was later the Byzantine capital of Italy). As the first bishop of Ravenna, he faced nearly constant persecution. He and his flock were exiled from Ravenna during the persecutions of Emperor Vespasian (or Nero, depending on the source). On his way out of the city he was identified, arrested as being the bishop, tortured and martyred by being run through with a sword.

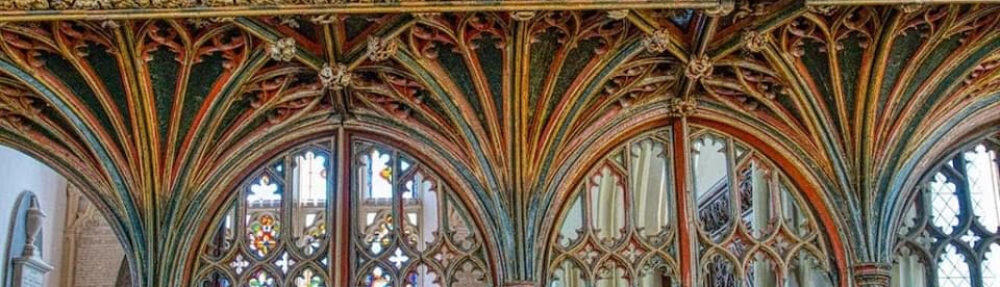

The church of San Apollinaire in Ravenna is a masterpiece, a jewel of Byzantine iconography and mosaics. It was erected by the Ostrogothic king Theodoric the Great during the first quarter of the 6th century. It was re-consecrated in AD 561, under the rule of the Byzantine emperor Justinian I, Justinian and his wife, the empress Theodora, appear in the mosaics of the church, each leading a segment of the offertory procession towards the altar during the celebration of the Eucharist.

The mosaics also depict a procession of the wise virgin-martyrs, led by the Three Magi, moving towards the group of the Madonna and Child surrounded by four angels. (The Magi in this mosaic are named Balthasar, Melchior and Gaspar; this is thought to be the earliest example of these three names being assigned to the Magi in Christian art.) The Magi are wearing trousers and Phrygian caps as a sign of their foreign origin. The gifts which the Magi and the wise virgins bring are reflections of the gifts which the congregation are bringing to present: bread, wine, water for the celebration of the Eucharist and food or clothes to be distributed among the poor and needy during the week.

The celebration of the Eucharist was often seen as a procession or pilgrimage in which the parish journeyed from earth to the Kingdom of God and then returned to earth to minister during the week what they had received on Sunday. During the celebration, the parish stepped outside time to stand alongside the Magi, the priest-king Melchizedek, Abraham and Isaac—all of whom also appear in the mosaics of this church—with the saints and martyrs of all times and places to worship God in eternity (as described in the Epistle to the Hebrews and the Book of Revelation, which are the first liturgical commentaries). The offertory procession is a visual shorthand to refer to the entire celebration.

The Magi were consistently venerated as the first non-Jews to come and worship Christ so they were considered the patron saints of all Christians of Gentile backgrounds. A shrine of the Three Kings at Cologne Cathedral, according to tradition, contains the bones of the Magi. Reputedly they were first discovered by Saint Helena on her famous pilgrimage to Palestine and the Holy Lands. The remains were first kept in the church of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople; they were later moved to Milan before being sent to their current resting place by the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I in 1164.

What prompts these thoughts about Ravenna, St. Apollinaire, and the Magi? The martyrdom of the saint and the translation of the relics of the Magi to Cologne are both commemorated on the same day (July 23).

Read more about the Magi in previous posts here and here and here.