Then I saw a strong angel proclaiming with a loud voice, “Who is worthy to open the scroll and to loose its seals?” (Apocalypse 5:2)

We encounter many figures in the Apocalypse who are mysterious at best and confusing at worst or commonly misunderstood. Angels might seem to be one of the more easily understood figures of the Apocalypse but we should not jump to such conclusions so quickly.

When reading early Christian texts like the Apocalypse, it is a rule of thumb that the animals and monsters we meet are there to stand in for people that the original readers might recognize–for instance, Roman emperors like Nero. Human figures are to be understood as angelic beings–like the “young men in white” who announce that Christ is risen to the women who meet them at Christ’s tomb. But figures who are introduced as angels–who are they?

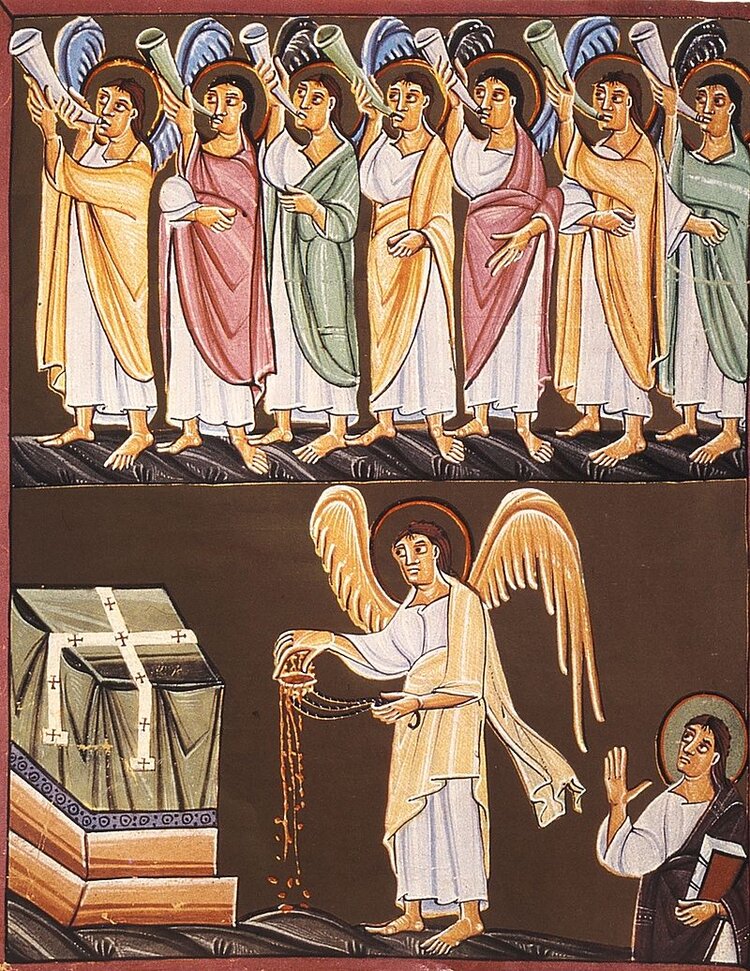

The angels in the Apocalypse are understood to be the deacons who serve at the eternal celebration of the Eucharist before the Throne of God, just as earthly deacons at the celebrations of the Eucharist were commonly understood to be angels, the “messengers” who announce the Gospel and the prayer intentions of the community and who make other liturgical announcements (such as “Let us bend our knees” or “Arise! Stand upright!” or “Bow your heads unto the Lord”) and who swing the censers-thuribles of smoking frankincense. The angels in the Apocalypse make similar announcements, such as calling forth the one worthy to open the scroll, and offering the incense that fills the air around the heavenly altar and the Throne of God. The angels-deacons of the Apocalypse tell the visionary author what to write and when to stand up or step forward.

The angel-deacons in the Apocalypse are also wearing vestments similar to those that earthly deacons wear during the celebration of the Eucharist: splendid tunics and sashes/stoles. (The stoles that earthly deacons wear are sometimes compared by early Christian liturgical commentaries with the wings of the angels, especially when the stoles are tied to one side to make the distribution of Holy Communion easier.)

Burning incense is one of the most important things angels-deacons do. The smell of incense is more than aroma therapy; it is profoundly theological. The sense of smell is an affirmation that we have bodies. Christ in his Incarnation came to save our entire being – body, soul, mind, and spirit, not just our intellects. The classical approach to Christian worship provides an embodied approach to worship.

Angelic figures in the Apocalypse are also sometimes compared to the eunuchs who function as imperial officials that keep the imperial system running. When the Apocalypse was written, eunuchs and angels were both thought to be asexual, beardless adults who served the imperial-heavenly court in a variety of ways–messengers, announcers, stenographers, record-keepers. Typically, eunuchs could not be ordained deacons but they could become monks.

Deacons! Angels! They coordinate the actions of the Eucharist on earth and in heaven, standing before the Throne and altar. They tell us what to do and when to do it. They burn the fragrant incense that nourishes the righteous and drives the devils away. They assist with the distribution of Holy Communion that also nourishes the faithful. They are one of the ways we unite what happens on earth with what happens eternally.