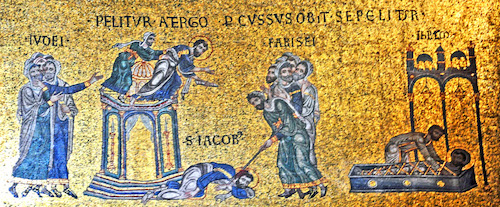

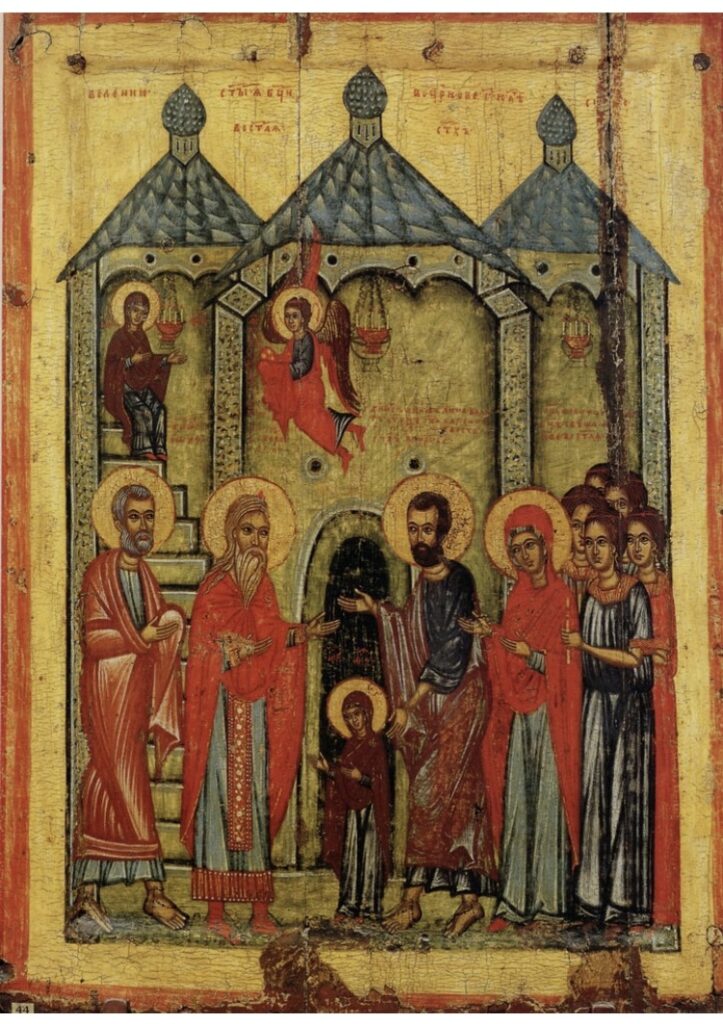

We read of the Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple when she was three years old in the Protoevangelium of James. SS. Joachim and Anna bring their daughter Mary to the Temple, as they promised to do before she was born, and give her to the service of God. Seven pairs of young girls march in procession with Mary. The priests meet this procession and take Mary into the Temple–into the Holy of Holies!–to live; she joins a community of women who care for the Temple fabrics and vestments. The archangel Gabriel brought the Blessed Virgin bread from heaven each day. When she was older, she was chosen to assist in weaving a new veil to hang before the Holy of Holies; it was while she was working with the purple thread to be used in the weaving that Gabriel appeared to her one last time, asking her to become the mother of Jesus (the Annunciation).

The two things in the story that usually strike people as outlandish or impossible is the assertion that the Blessed Virgin enters the Holy of Holies itself and that she grows up at the Temple, cared for a community of woman in the Temple compound.

The Virgin is said to enter the Holy of Holies because she herself becomes the Holy of Holies–the innermost sanctuary where God dwells. Clearly, it would have been impossible for a three-year old to “accidently” enter the Holy of Holies as it was heavily guarded and protected; the Holy of Holies here stands for the Temple itself in its entirety as well as its being synonymous with the Virgin herself.

The community of women who live at the Temple is alluded to by St. Luke in his Gospel by the Prophetess Anna (in Luke 2), an elderly woman who meets Christ in the Temple when he is forty days old. But the story in the Protoevangelium still strikes many as unlikely. Throughout the Old Testament we read of women who waited at the door of the Temple or the Tent of Meeting in the wilderness (Exodus 38:8; Numbers 4:23, 8:24; 1 Sam. 2; as well as 2 Maccabees 3).

We have also recently made archeological discoveries that reveal the presence of a 3-story women’s dormitory alongside the Temple and we read in Josephus (an important 1st century historian) that the young women and their chaperones made a Nazarite vow and who lived in this dormitory; he also tells us that these young women (virgins) jumped out of the windows into fires below to avoid being attacked, raped, and killed by the Roman soldiers who pulled down the Temple in AD 70. Jewish sources–such as the Mishnah and the Talmud–tell us that a community of women were, in fact, responsible for the care of Temple linens as well as baking the showbread and mixing the incense to be used.

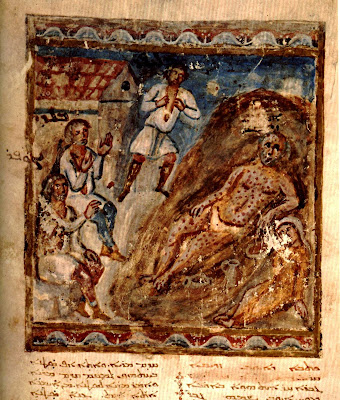

That the Virgin is presented when she is three-years old relates to the expectation that children were weaned at that age and the prophet Samuel was given to the priest Eli when the boy was three-years old. Heifers and other animals to be sacrificed were also three-years old when given as offerings to God. The archangel Gabriel is said to bring her bread from heaven because she eventually gives birth to the Living Bread, the True Bread come down from heaven. In the meanwhile, she is sustained by a rich life of prayer and devotion to God.

The story of the Presentation of the Virgin makes the point that the two most important signs of the Old Covenant become flesh in the New Covenant: the Torah–the living Word of God–is made flesh in Jesus and the Temple–the place where God dwells and where people can meet him–becomes a woman. The Protoevangelium recalls many details of 1st century Jewish life that were otherwise forgotten for centuries and is more reliable as a source than many people realize.