Likewise, was not Rahab the prostitute also justified by works when she welcomed the messengers and sent them out by another road? For just as the body without the spirit is dead, so faith without works is also dead. (James 2:25-26)

So, just who was this “Rahab, the prostitute” that the Apostle James is talking about in the same paragraph as the patriarch Abraham? These two figures from the Old Testament–Abraham and Rahab–are the two most important people that St. James can cite as examples of his point about the necessity of faith-works going together. Rahab must have been quite someone to rank up there with Abraham.

In the book of Joshua, chapters 2 and 6, we are told the story of the spies Joshua sends into the city of Jericho before the Hebrews attacked it. Rahab, a prostitute, hid the spies and made a deal: the Israelite army would spare her and her family when they attacked and massacred the city. Joshua agreed to this. After the city of Jericho was attacked and Rahab’s family spared, she is said to have become the great-great-grandmother of King David; thus, Rahab is an ancestor of Christ.

Although her status as a sex worker might make us think Rahab a person outside the Kingdom of God, it is her action based on her faith in the God of Israel which saves her–and the people of Israel and eventually the world as her bravery and foresight make the Incarnation possible. Her response to God is just as important as Abraham’s — both of them were necessary to save the world.

Early Christian teachers and preachers frequently mentioned Rahab as a woman who demonstrated many virtues (faith, hospitality, repentance) as well as a model for Christians living “in the world” and as a harbinger of salvation. Read more about these sermons here.

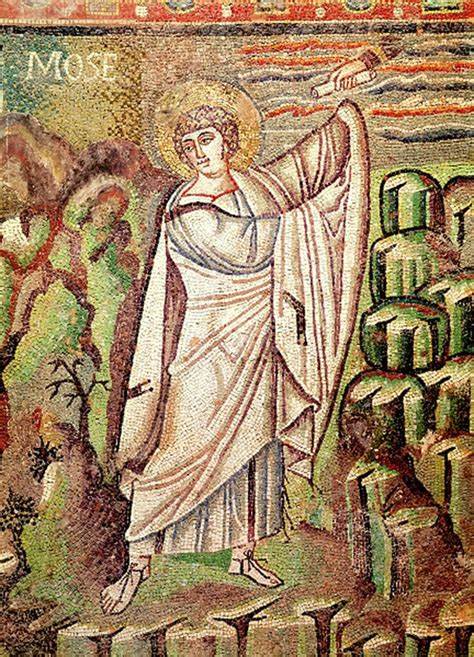

In the mosaic above, we see the visit of the “prince of the host of the Lord” to Joshua before the conquest of Jericho (Joshua 5:13-15). That he is an angel is indicated by a halo rather than wings, and his military garb expresses his role as leader of a host. In the text he has a “drawn sword,” but here it is a labarum such as the archangel Michael carries in Byzantine icons.

Seeing this person, Joshua “fell on his face to the ground.” In the mosaic we see only the beginning of this movement.

The lower register illustrated Joshua 2:1-21. Joshua on the left tells his two spies to reconnoiter in Jericho. On the right, the prostitute Rahab (wearing green and standing on the battlements of the city) helps them escape by climbing down the wall.