“Mercy and truth have met together; righteousness and peace have kissed each other. Truth shall spring up from the earth, and righteousness shall look down from heaven.” (Psalm 85:10-11)

These four virtues–mercy, truth, righteousness, and peace–are often referred to as “the four daughters of God.” The virtues come to be seen as personifications, four celestial women, similar to angels or archangels. The most important contributors to the development and circulation of the motif were the twelfth-century monks Hugh of St Victor and Bernard of Clairvaux. (Christian thought might have have been inspired by an earlier eleventh-century Jewish Midrash, in which Truth, Justice, Mercy and Peace were the four standards of the Throne of God.)

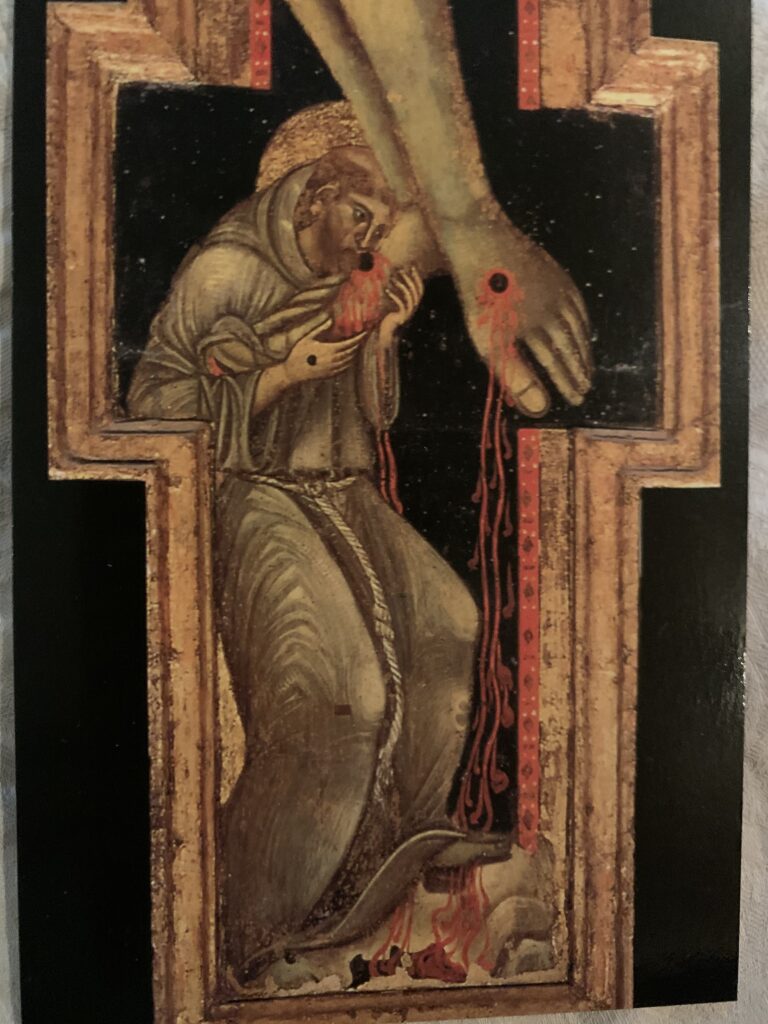

The four daughters might sometimes be thought to be gathered around Christ on the Cross as they–all four–are manifest in differing ways by the Crucifixion and Resurrection of Christ. The verse, “Truth shall spring up from the earth and righteousness … look down from heaven” might also be associated with the Nativity of Christ and his–Truth’s–springing up on the earth and being laid in a manger while Righteousness–the other persons of the Holy Trinity–look down on the scene in Bethlehem. The association of the four daughters with the Incarnation is underscored because they also appear in two sermons by St. Guerric of Igny on Luke 2 “for February 2:

“In this gathering [of the Virgin Mary, Christ, St. Joseph with SS. Simeon and Anna] finally mercy and truth have met … the merciful redemption of Jesus and the truthful witness of the old man and woman. In this meeting, justice and peace kissed when the justice of the devout old man and woman and the peace of him who reconciles the world were united in the kiss of their affections and in spiritual joy.” (Sermon 16.6)

“Rightly then are compassion and truth or faith joined together, since in all our ways–unless compassion and truth meet–it is to be feared that sins will be increased rather than purified…. [There is no forgiveness] if compassion is lacking faith or faith, compassion.” (Sermon 18.5)

The motif of the four daughters of God was influential in European thought. In 1274-76, Magnus VI of Norway introduced the first “national” law-code for Norway and makes prominent use of the allegorical four daughters of God: Mercy, Truth, Justice, and Peace. These daughters have the important role of expressing the idea—which was innovative in the Norwegian legal system at the time—of equality before the law.

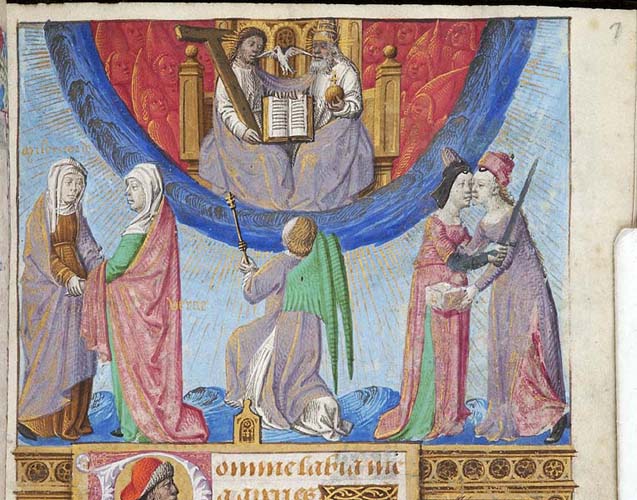

The motif changed and developed in later medieval literature, but the usual form was a debate between the daughters (sometimes in the presence of God):

about the wisdom of creating humanity and about the propriety of strict justice or mercy for the fallen human race. Justice and Truth appear for the prosecution, representing the old Law, while Mercy speaks for the defense, and Peace presides over their reconciliation when Mercy prevails. *Michael Murphy, ‘Four Daughters of God’, in A Dictionary of Biblical Tradition in English Literature, ed. by David Lyle Jeffrey (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1992), pp. 290-91. )

This psalm is also often suggested in traditional prayer books as a preparation for receiving Holy Communion. The communicant prepares to join the fellowship of the daughters of God by receiving the Body and Blood of Christ.