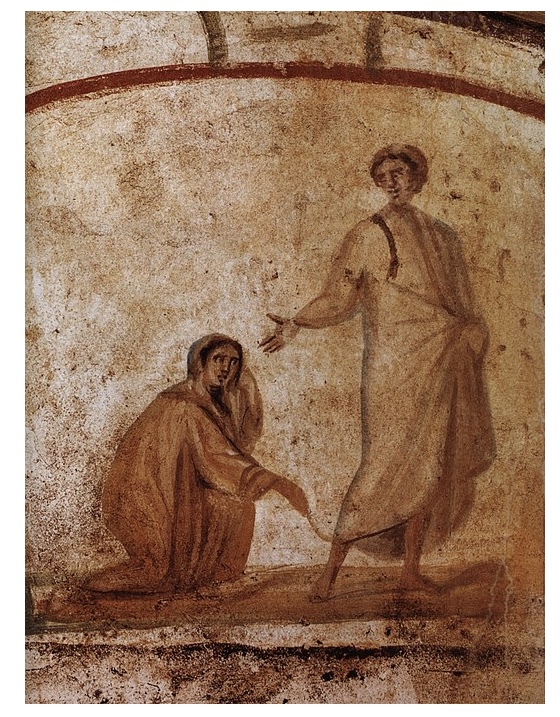

A good man? Moses’ father-in-law, Jethro, is a devoted family man, well respected for his advice on governing and his benevolent leadership of the tribes of Midian. This early 13th-century illustration from the Bible moralisée depicts Jethro (seated under the arch on the right) rewarding Moses (left) for rescuing his daughters (six of whom are pictured in the center) and their flocks from rival shepherds.

Jethro, to most people, was the not-so-bright son of Jed and Granny on “The Beverly Hillbillies.” How many realize that Jethro was the name of Moses’ father-in-law? Jethro was “priest and prince of Midian,” the area where Moses encountered the Burning Bush.

Jethro comes to Moses in the wilderness of Sinai, before the giving of the Ten Commandments, because he is bringing his daughter–Moses’ wife–back to him. Although the text does not tell us this earlier, she evidently took their children and went to her father for safekeeping during Moses’ confrontation with Pharoah; when Moses tells Jethro everything the Lord did for the people, including the plagues, this is all news to Jethro. If his daughter had seen any of this, she would have told him; evidently, she left Moses in Egypt before the plagues began. In thanksgiving for the deliverance of the people, Jethro offers a large sacrifice and invites all the clan leaders to the feast that follows.

The text tells us that Jethro is priest-and-prince. We already knew that he was wealthy because of the description of his large flocks when Moses first meets him. Whether Jethro was a wealthy herdsman who was therefore acknowledged as “prince” or was the prince and therefore was wealthy, we don’t know. But the linkage of royalty and priesthood only occurs one other time in the Old Testament: the priest-king Melchizedek who blesses Abraham and is seen as a “type” of Christ by the Epistle to the Hebrews.

Medieval rabbis were eager to avoid the embarrassment of Moses having a pagan priest-prince as a father-in-law and so they began to suggest that Jethro was circumcised after he heard the recitation of God’s mighty acts of deliverance–after he heard what became the Passover haggadah, in effect. This made Jethro, like Melchizedek, a legitimate priest before Aaron and his sons were made a legitimate priesthood. This makes Jethro, like Melchizedek, a foreshadowing of Christ–the Son of David who is both priest and king on the Cross. Jethro, however, was not the focus of the typology in the Epistle to the Hebrews because he did not evidently live forever, like Melchizedek did; Jethro was an imperfect type of Christ, the ultimate king-priest who is eternal.

Nevertheless, this makes for fascinating speculation about Moses–raised as a prince of Egypt– and his immediate family as Middle Eastern royalty and their connection to priesthood in both Moses’ father-in-law (Jethro) and his brother (Aaron).