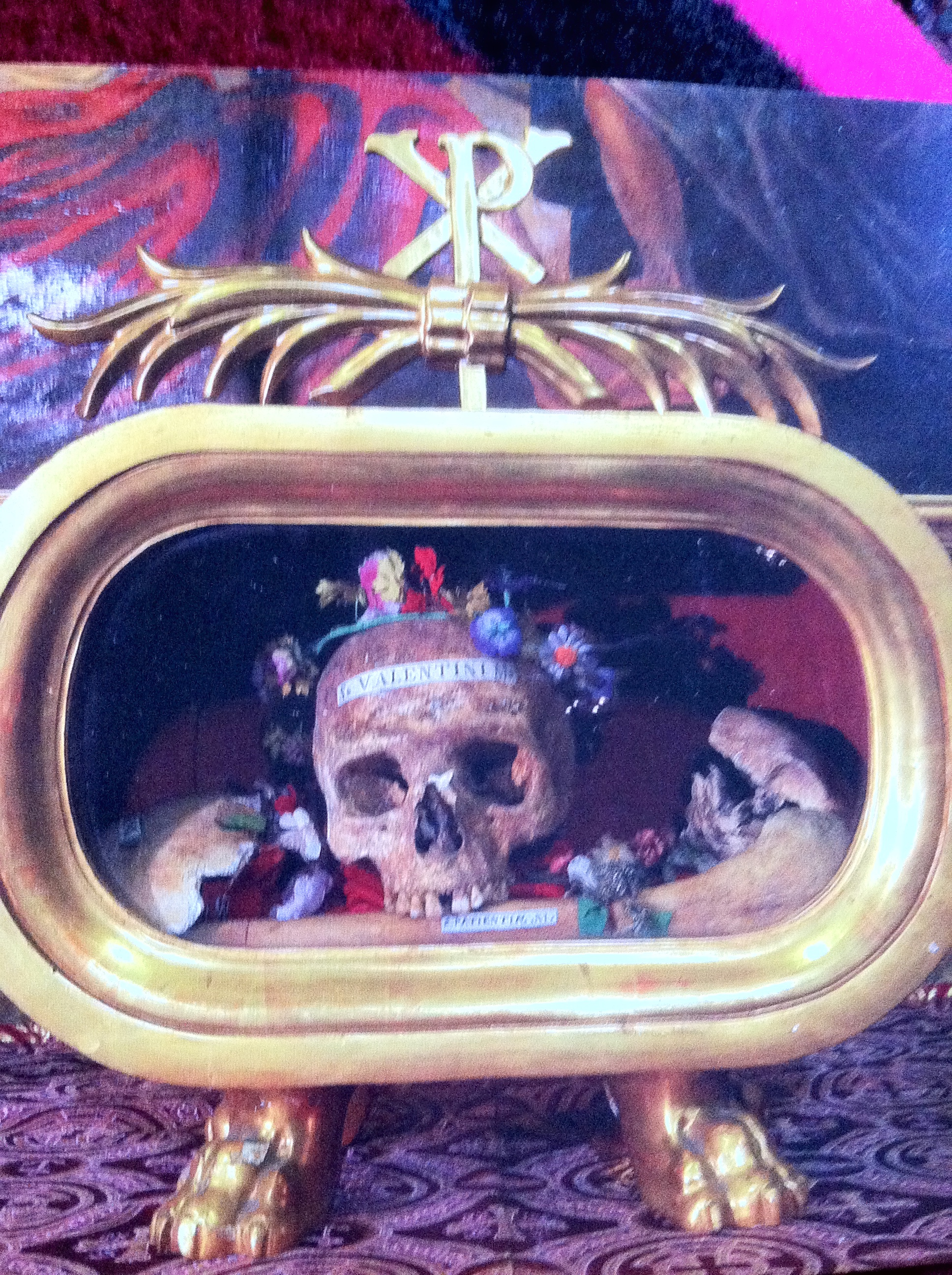

The skull and other relics of St. Valentine, a priest martyred in Rome during the early centuries of Christianity, now kept on a side altar in the Basilica of Santa Maria in Cosmedin in Rome.

With the modern celebration of Valentine’s Day nearly upon us, can thoughts of love magic be far behind? A number of traditional ways to win another’s heart have been used over the years. One way a woman could win a man’s heart was by feeding him food into which she had mixed some of her own blood (menstrual blood was especially effective). Catching the reflection of mating birds in a mirror on Thursday was the first step in a more complicated love spell. After catching the reflection, a person would give the mirror to his or her chosen and once the receiver looked into the mirror, they would be irresistibly infatuated with the mirror-giver. Or a woman might resort to the much more simple use of caraway seeds, cloves, or coriander to win the affection of the man she had chosen. One English love potion included the kidney of a rabbit, the womb of a swallow, and the heart of a dove while an ancient Greek love potion used a stallion’s semen or a mare’s vaginal discharge.

Garlic, saffron, ginger, or even vanilla(!) were more likely to be used in erotic magic, which was less concerned with affection, and more likely to be aimed by men at women. Wax images could be pierced by pins to incite lust. Striking the intended with hazel or willow branches was also thought to inspire lust. Or you could obtain a few hairs from your intended’s head, tie them in a knot with twine, and then keep the amulet on your thigh or around your genitals to draw your intended’s attentions.

Of course, there were ways to deflect this sort of magic as well. Lily or lettuce could break love spells or decrease lust and thwart unwanted attentions. Just be sure not to confuse which herbs you feed to which guest at your table!