Statue of Saint James the Moor-slayer or Santiago Matamoros in the Cathedral of Burgos, Castille, Spain

Tradition has it that the Apostle Saint James preached in Spain. He then returned to Jerusalem, where Herod executed him. The corpse was then placed in a ship that arrived at Spain. The tomb was forgotten until the year AD 813, when a hermit noted lights and songs around the place. The hermit told the local bishop who–after removing some weeds–discovered the remains of the apostle identified by the inscription on the tombstone. He reported the discovery to King Alfonso II, who came to the scene and proclaimed the Apostle Sant Iago (Saint James) patron of the kingdom. The area was then renamed as Campus Stellae, the “Field of Stars,” from which the current name, Compostela, has been derived.

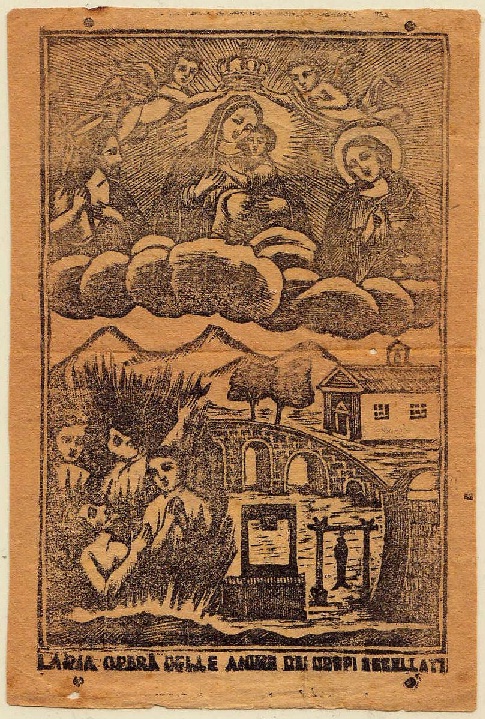

During the Battle of Clavijo, it is said that Saint James the Great miraculously appeared to provide assistance to an outnumbered Spanish Christian army, helping them gain victory against the Moors who had started their conquest of Spain in AD 711. The battle is placed between AD 834 and 844, about 800 years after the death of James. According to legend, Saint James appeared as a warrior on a white horse amidst the Spanish army, wielding a white banner. Upon seeing him, the Christian army cried out “¡Dios ayuda a Santiago!” which translates to “God save St. James!” It is believed that more than 5,000 Moors were killed during the battle, earning James the title Matamoros or “Moor-slayer”.

Many historians argue that the Battle of Clavijo never took place and that it was a myth based on the historical Battle of Monte Laturce (AD 859). The legend only appeared in writing nearly 300 years after its alleged occurrence. However, while it was based on legend, the story of the battle helped establish Spain’s national identity.

See an article from The Guardian about St. James the Moor-slayer here.