And I came to you, brothers and sisters, not with the advantage of rhetoric and wisdom …. not with persuasive words of wisdom but in the demonstrative proof of the Spirit and power. (1 Corinthians 2:1, 4)

St. Paul reminds the Corinthians that he did not preach to them and among them with fancy words and Greek philosophy but simply, relying on the Spirit of God to demonstrate the power and truth of his words. His sermons wouldn’t win an oratory prize, he says. But his sermons did win their hearts.

A third-generation Christian bishop, Irenaeus of Lyons, wrote a Demonstration of Apostolic Preaching to accomplish the same thing that St. Paul was aiming for: teaching or reminding new converts the basic Christian understanding of the world and how to relate to it from a Christian perspective. His other famous work, Against Heresies, refutes the teachings of several different heretical sects that claimed to be Christian; in both works, St. Irenaeus establishes fundamental principles of theology and biblical interpretation that still guide Christian readers and thinkers.

Irenaeus was born in Smyrna. He was taught the Faith by St. Polycarp, who had been taught by the Apostle John. In the Demonstration, St. Irenaeus reviews salvation history in the Old Testament and then cites several Old Testament prophecies about the Messiah, explaining how Christ fulfilled them. St. Irenaeus writes

This, beloved, is the preaching of the truth, and this is the manner of our redemption, and this is the way of life, which the prophets proclaimed, and Christ established, and the apostles delivered, and the Church in all the world hands on to her children. This must we keep with all certainty, with a sound will and pleasing to God, with good works and right-willed disposition.

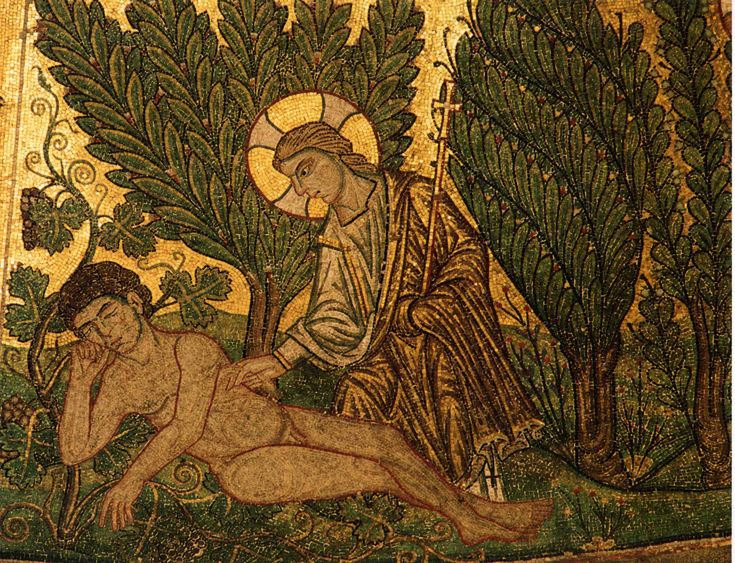

One of St. Irenaeus’ most interesting ideas is that of “recapitulation,” in which he teaches that Christ and his mother summarize and set right everything that went wrong with Adam and Eve; he points out that Christ is the Second (Last) Adam and Mary is the Second Eve:

For in what other way could we have partaken in the adoption of sons, unless we had received from him [God the Father] fellowship with himself through the Son? Unless his Word, having been made flesh, had entered into fellowship with us?

For this reason, he also passed through every stage of life, restoring fellowship with God to all [stages of life]….

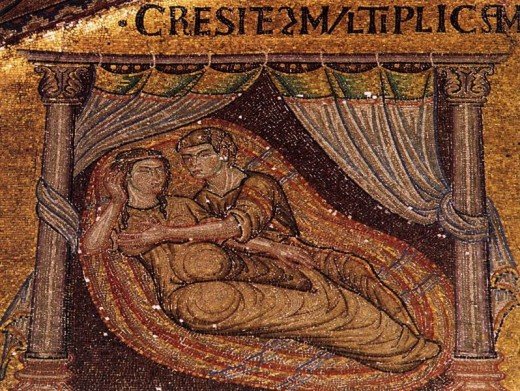

The human race fell into bondage to death by means of a virgin, so is it rescued by a virgin; virginal disobedience having been balanced in the opposite scale by virginal obedience. For in the same way the sin of the first created man received amendment by the correction of the First-begotten, and the coming of the serpent is conquered by the harmlessness of the dove, those bonds being unloosed by which we had been fast bound to death.

St. Paul and St. Irenaeus both want to demonstrate how God has acted in the past to save his people and how God continues to act in the lives of his chosen. Those who have experienced God’s acts of deliverance are called to demonstrate this by responding appropriately. Most of the rest of the first letter to the Corinthians is about what this demonstrative response to God appropriately looks like.