“Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy.” (Exodus 20:8)

The 10 Commandments are prefaced with the proclamation that Israel ought to keep the commandments because “I am the Lord your God, who brought you out of Egypt, out of the land of slavery.” The delivery from Egypt is what obliges Israel to keep the commandments as an act of gratitude. But the Sabbath is different—Sabbath is hardwired into the DNA of creation because God rested on the Sabbath when making the world.

The command to “Remember!” the Sabbath is not the same word as in the command, “Do this in remembrance of me” at the Last Supper. Remembrance of the Sabbath is the Future Passive Indicative 2nd Singular form of the verb, meaning “you shall remember,” or “you shall recall,” “you shall think about,” “you shall be aware of.”

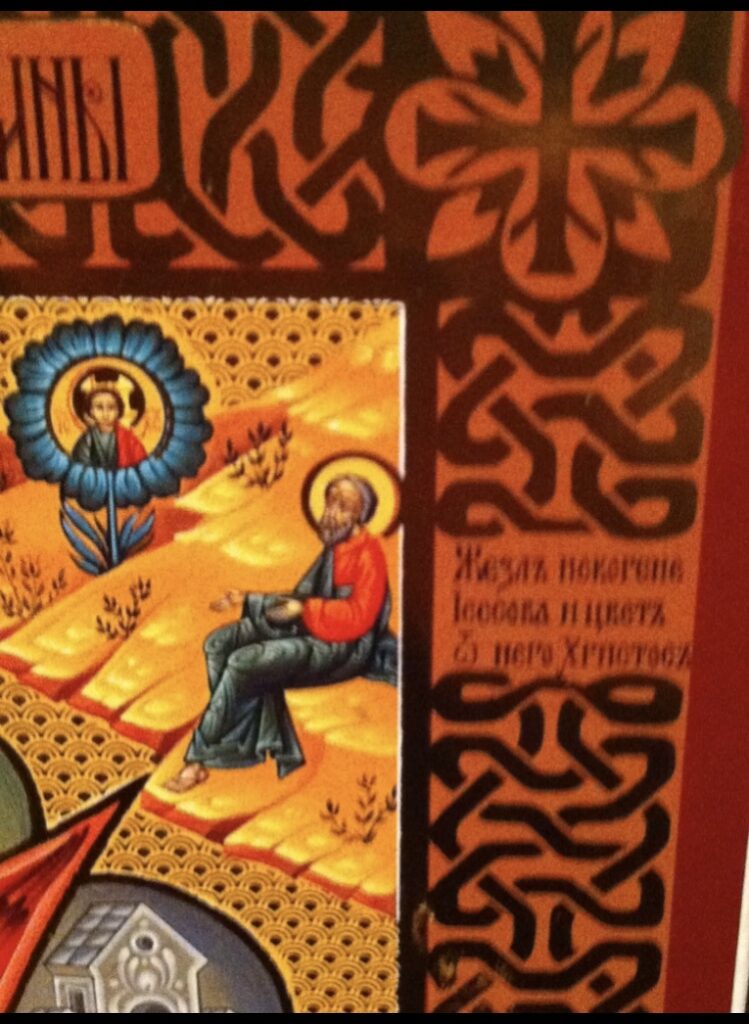

This form of “remember” is always looking ahead to something. The people are told to always live in expectation, in anticipation of the next Sabbath. The Sabbath is the chronological icon of the Kingdom of God: just as we are called to always live in expectation and hope for the Kingdom, the 10 Commandments tell the people to always live in expectation and hope of the next Sabbath. They-and we-are called to focus on the future, where we are going rather than being focused on the past, where we have been and what we have done. We look ahead and we hope.

Several years ago, I was on West 14 Street several times a week during the summer for various regular errands. There was a street-lady, disheveled and unkempt, who walked backward pushing the shopping cart of her possessions nearly every day. In the Old Testament, she would have been hailed as a prophet enacting a sermon everyday, a living example of how people spend more time paying attention to where they have been and despairing over or being proud of what they have done rather than paying attention to where they are going and hopeful about opportunities and challenges ahead.

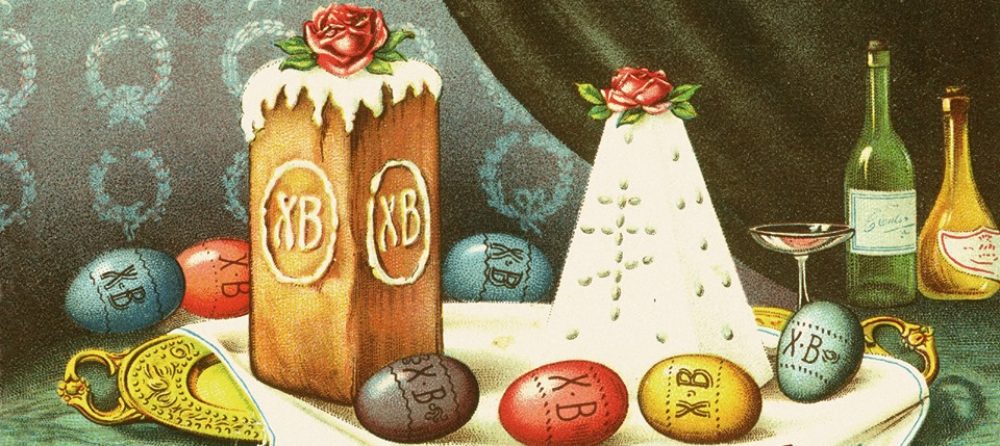

In modern Greek, this form of the verb has become the word for “fiancé.” This suggests that the Sabbath is the “engagement ring” given by God to his bride, Israel. Many of the prophets refer to the forty years that Israel spent in the wilderness as their honeymoon period with God.

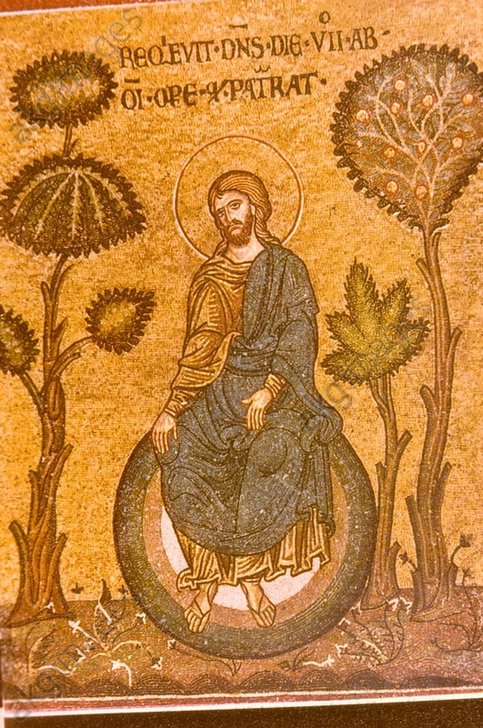

Sabbath has always been respected in the Christian liturgical practice even as Sunday, the weekly anniversary of the Resurrection, became the principal day of Christian worship. Of course, the Great Sabbath—the ultimate day of rest—is the blessed Sabbath that Christ spent resting in the tomb, during which he descended into Hell to harrow [demolish] it. The engagement of God to Israel is fulfilled when Death and all-that-opposes-God is destroyed and the wedding celebration described in the Apocalypse [Book of Revelation] begins.

(Readers will recall that the Greek text of the Old Testament was compiled in 300 BC while the standard Hebrew text as we now have it is only as old as the First Crusade , AD 1000. The Septuagint, 1300 years older than the Hebrew text that survives, is a more reliable witness—translated by Jewish scholars for Jewish readers—to the original text. I’m classical Christian thought, the medieval Hebrew is a commentary on the text rather than the source of the text itself.)