St. Francis of Assisi is known for many things. Several episodes in his life have become part of popular culture, some still associated with his name while his connection to others has been forgotten: how many remember that the Christmas manger scene–the creche–was “invented” by St. Francis in 1223?

“For in the day of trouble he [the Lord] shall keep me safe in his shelter; he shall hide me in the secrecy of his dwelling, and set me high upon a rock.” (Psalm 27:7)

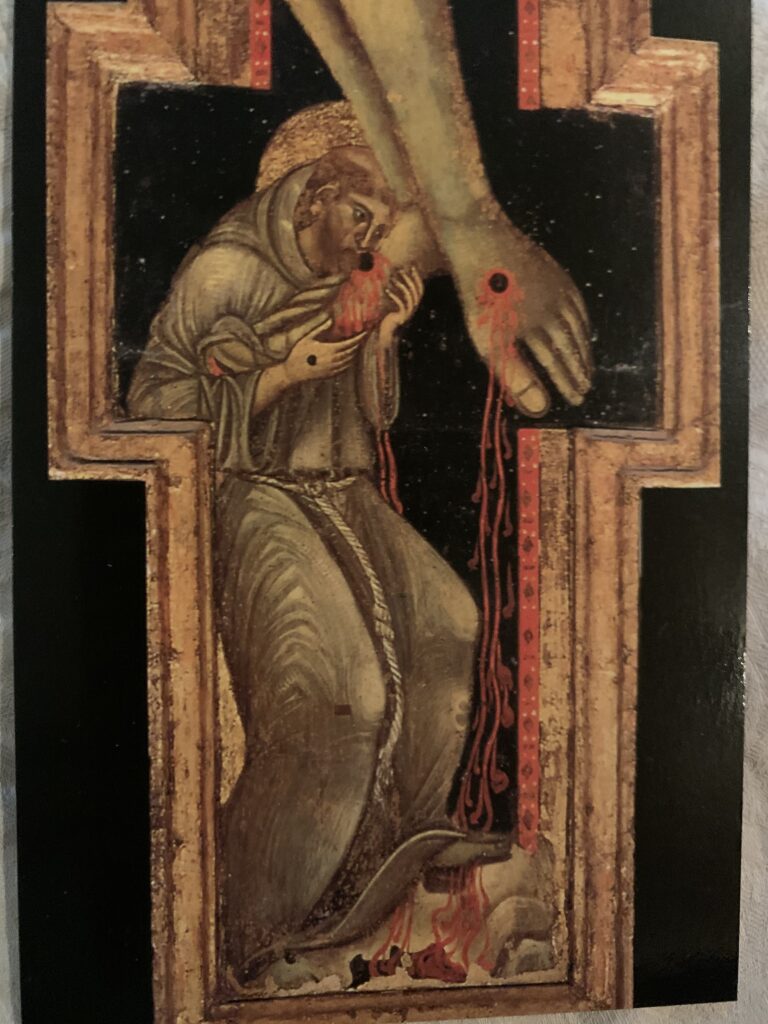

As I was reading the psalms last week, I was reminded of another incident in St. Francis’ life. In the autumn of 1224 (the year after he organized the first creche), St. Francis received the stigmata (meaning “brand” or “mark”)–the five wounds of Christ–although this was not generally known until after his death in 1226. The stigmata is commonly referred to as “the wounds of love” described by the bride in the Song of Songs 2:5. The groom then tells the bride, “Come, my dove, in the cleft of the rock…” (Song of Songs 2:13-14).

We are told by St. Gregory of Nyssa that this cleft “is the sublime message of the Gospel” and the person who loves God is not coerced to take refuge in the Gospel but must freely choose to love God and the Good News; St. Gregory points out that King David “realized that of all the things he had done, only those were pleasing to God that were done freely, and so he vows that he will freely offer sacrifice. And this is the spirit of every holy man of God, not to be led by necessity.” What is coerced is not love. Love must be freely given and freely received. Taking refuge in the rock is to freely give oneself to God and to be freely received by God.

The psalm refers to this same idea: the Lord will protect his friend, his beloved from danger by sheltering the beloved in the “secrecy of his dwelling,” the cleft “high upon the rock.” Readers–such as Augustine of Hippo–understood this psalm to promise freedom from sin to the beloved of God; the one who loves God would be kept safe from the danger of damnation even if slain by enemies.

Medieval poets often identified the “cleft in the rock” mentioned by the Song and the psalms with the wounds of Christ, especially the wound in Christ’s side made by the spear. Early Christian authors, such as St. Methodius of Olympus, preached that “Christ slept in the ecstasy of his Passion and the Church–his bride–was brought forth from the wound in his side just as Eve was brought forth from the wound in the side of Adam.”

The stigmata was the seal of St. Francis’ love for God and God’s love for Francis. It was in the refuge of this love that Francis found the safety to love the world which was in such need.