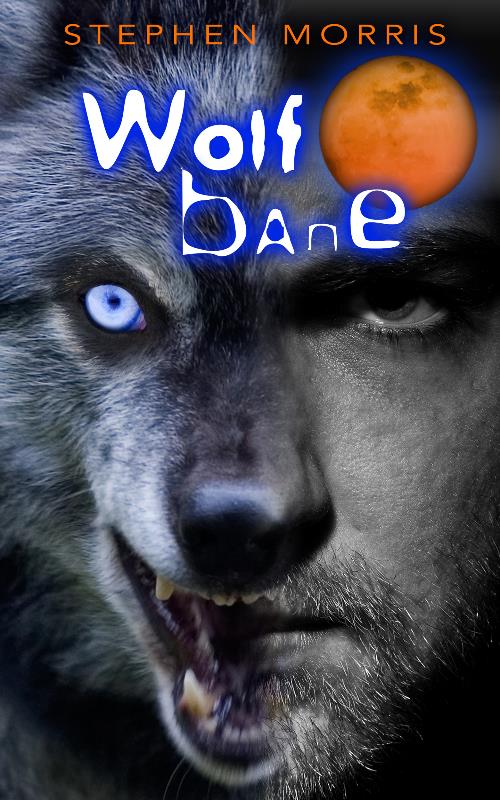

In WOLFBANE, Alexei inherits his grandfather’s magical wolf-pelt and thereby assumes the position of village “metsatöll” (Werewolf) in rural late 1880s Estonia to protect the area by fighting the terrible storms in the sky that could devastate the farms and fields. But he breaks the terms of the wolf-magic and loses the ability to control the shapeshifting, becoming a killer. Heartbroken at what he has become, Alexei flees his home in hopes of finding an enchanter who can free him from the curse.

Although I had hoped to release a full-length novel featuring Alexei by the end of 2014, another project took my attention but I now have the time to come back to Alexei. I have begun the research and planning necessary for the novel and have written two chapters in Alexei’s unfortunate series of adventures which will take him through Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland or Slovakia and Bohemia. Although these are now individual nation-states, there had been unions of Estonia-Latvia and Latvia-Lithuania dating from the Middle Ages, making for broad sweeps of common cultural heritage(s). There is a wealth of fascinating folklore and history to draw on from these regions which, combined with the social upheavals of early industrialization during the 1800s, promise exciting twists and turns as Alexei makes his way in search of liberation and redemption.