I remember studying about Santa Lucia in third grade when Scandinavia was the Social Studies unit. (I also remember the teacher saying that reindeer herding was one of the primary occupations in Finland and I wanted to ask, “How can anyone herd reindeer when they can fly?!” But something told me to keep my mouth shut. I’m glad I did.) Three years ago, I was also able to visit her relics which are currently kept in Venice.

Saint Lucy’s Day, is celebrated on 13 December, commemorating Saint Lucy (a 3rd-century martyr under the Great Persecution of Diocletian), who according to legend brought “food and aid to Christians hiding in the catacombs” wearing a candle-lit wreath on her head to “light her way and leave her hands free to carry as much food as possible”. Her feast once coincided with the Winter Solstice, the shortest day of the year before calendar reforms, so her feast day has become a Christian festival of light.

Saint Lucy’s Day is celebrated most commonly in Scandinavia, with their long dark winters, where it is a major feast day, and in Italy, with each country highlighting a different aspect of the story. In Scandinavia, where Saint Lucy is called Santa Lucia, she is represented as a lady in a white dress (a symbol of a Christian’s white baptismal robe) and red sash (symbolizing the blood of her martyrdom) with a crown or wreath of candles on her head. In Norway, Sweden and Swedish-speaking regions of Finland, as songs are sung, girls dressed as Saint Lucy carry cookies and saffron buns in procession, which symbolizes bringing the light of Christianity throughout world darkness.

St. Lucy is the patron saint of the city of Syracuse (Sicily). On 13 December a silver statue of St. Lucy containing her relics is paraded through the streets before returning to the Cathedral of Syracuse. Sicilians recall a legend that holds that a famine ended on her feast day when ships loaded with grain entered the harbor. Here, it is traditional to eat whole grains instead of bread on 13 December. This usually takes the form of cuccia, a dish of boiled wheat berries often mixed with ricotta and honey, or sometimes served as a savory soup with beans.

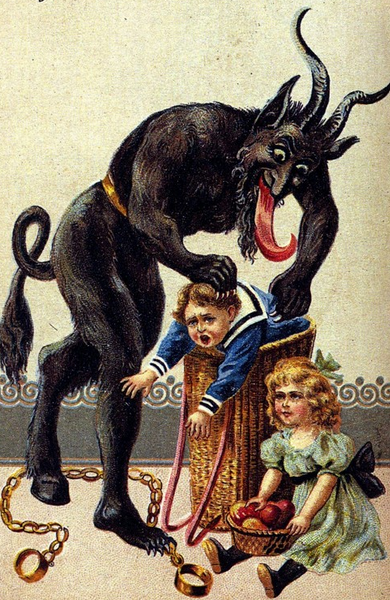

St. Lucy is also popular among children in some other regions of Italy, where she is said to bring gifts to good children and coal to bad ones the night between 12 and 13 December. According to tradition, she arrives in the company of a donkey and her escort, Castaldo. Children are asked to leave some coffee for Lucia, a carrot for the donkey and a glass of wine for Castaldo. They must not watch Santa Lucia delivering these gifts, or she will throw ashes in their eyes, temporarily blinding them.

I think that in the United States, Santa Claus might appreciate a cup of coffee as well, more than milk and cookies!