The dragon guarding the Southwark landing of the London Bridge is the location of an important episode in Kate Griffin’s “Midnight Mayor.”

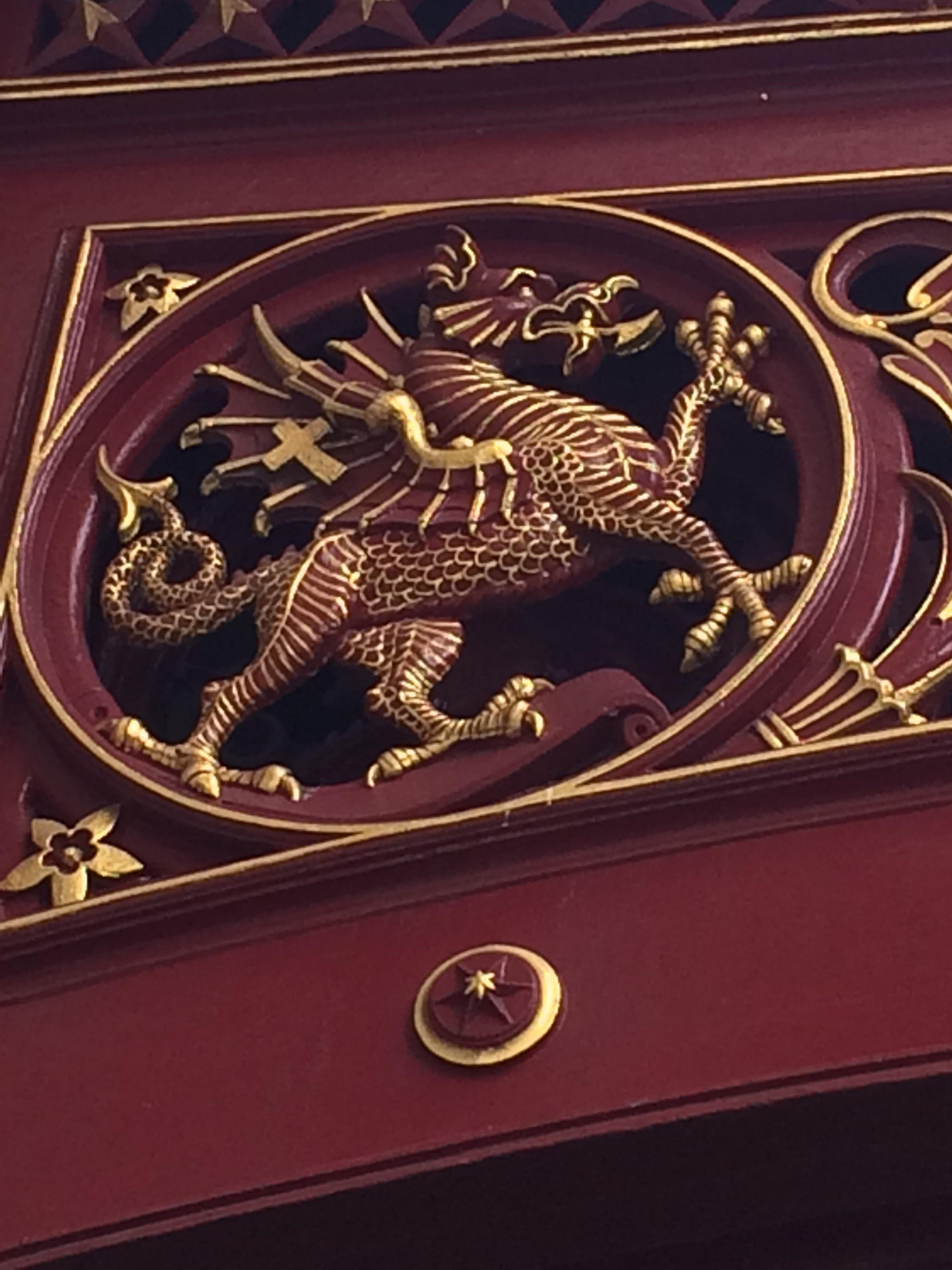

At the heart of London are two cities: the City of London and the City of Westminster. The City of London is the ancient part of London that was once known as the Roman city of Londinium. It comprises an area of one square mile and is located north of South Bank and London Bridge. Dragons stand guard at the ancient gates into the ancient city of London, at the bridges and main streets that now bring people into and out of old London. As guardians or gatekeepers of the City all the dragons face outwards, so if the dragon is looking at you, you’re outside the City, if he has his back to you, you’re inside the City. The dragons are poised to protect the City from those coming to attack.

The dragons lean on the shield of London, which show a red cross on a white background and a small red sword. red cross on a white background is the flag of St. George, patron saint of England (along with many other nations around the world). Inside the top left-hand quarter of the flag there is an upright red sword. This commemorates St. Paul, the patron saint of the City of London. Since the 7th century there has been a cathedral dedicated to St Paul on Ludgate Hill in the City. The sword commemorates Paul’s beheading by sword in Rome c. 66 AD during the persecution of Christians under Nero. The Latin motto of London, “Domine dirige nos” (“O Lord, direct/guide us”) is also seen below the dragon and shield.

Why dragons? The reason seems lost in the mists of time. Some suspect the London dragon–which is silver or white–is an old Saxon emblem set to attack the ancient Welsh emblem of another (red) dragon. Some think the London dragon is derived from the story of St. George. Others think that the London dragon is just another dragon commonly used in heraldry to display coats-of-arms and shields. But I like how Kate Griffin describes the dragon that simply IS London in her novel Midnight Mayor:

It was…

…dragon didn’t quite cover it.

Dragon implies something made out of scales, with a nod in the direction of reptilian ancestry: dinosaur meets flamethrower with wings….

To say it was made of shadows would be to imply that light or darkness even got a look-in. Sure, it had crawled out if them, in the way that the diplodocus had once crawled out of the ameba of the sea. And if a comet came from the heavens to smash it, it wouldn’t be squished, just spread so wide and thin across the earth that it would look like night had fallen down, dragging all the stars with it–before, with a good thorough shake to push the stardust off its skin, the creature slid back to its brilliant, angry, maddened shape.

Of course, the dragon might itself be said to have attacked the City in the Great Fire. The Great Fire of London was the conflagration that swept through the central parts of the City from Sunday, 2 September to Thursday, 6 September 1666. The fire gutted the medieval City of London inside the old Roman city wall.

A dragon on the Holborn Viaduct in London. (photo by S. Morris)