“The Golem and the Jinni,” by Helene Wecker was nominated for the Nebula Award for Best Novel and the World Fantasy Award for Best Novel, and won the 2014 Mythopoeic Award.

These two books–one a novel, the other a study of Arab immigrants to Manhattan’s Lower East Side–are a fascinating pair to read in conjunction with each other. The Golem and the Jinni by Helene Wecker tells the story of two mythical beings–one Jewish, the other Syrian– which takes readers on a dazzling journey through cultures in turn-of-the-century New York. Strangers in the West: The Syrian Colony of New York City, 1880-1900 by Linda K. Jacobs tells the never-before-told story of the first Arab immigrants to settle in Manhattan.

Both books explore many themes but one that stands out is the tolerance individuals from each community had for the other even as each community–as well as the broader society of Manhattan–struggled with the presence of those they each considered “the Other.” The twists and turns of the novel reflect the twists and turns of historic life for the immigrants who struggled to make new lives for themselves and their families in the New World. (I never quite appreciated how radical the idea of the New World was until I saw The Hunt for Red October (based on Tom Clancy’s book) and heard Jack Ryan (Alec Baldwin) welcome Soviet submarine captain Marko Ramius (Sean Connery) to the New World after Capt. Ramius quotes Christopher Columbus’ musings that “the sea will grant each man new hope, as sleep brings dreams of home.”)

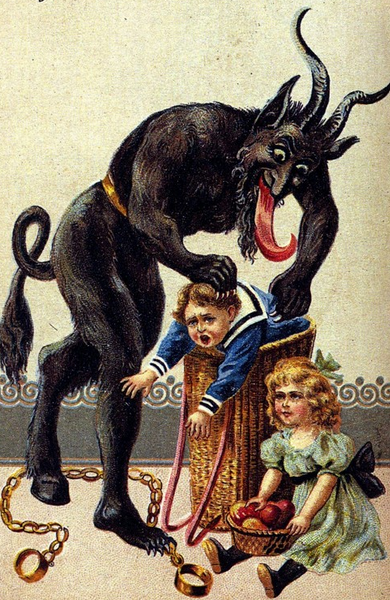

Too many people seem too eager to demonize a wide variety of “Others” in modern society. Add either–or BOTH!–of these books to your “Want to Read” list and see how we were able to overcome such attempts at demonization in the past while enjoying wonderful storytelling!

Want to know more? Read the Huffington Post article about Strangers in the West or my post about The Golem and the Jinni.