Precursors of April Fools’ Day include the Roman festival of Hilaria, held March 25, and the medieval Feast of Fools, held December 28, still a day on which pranks are played in Spanish-speaking countries.

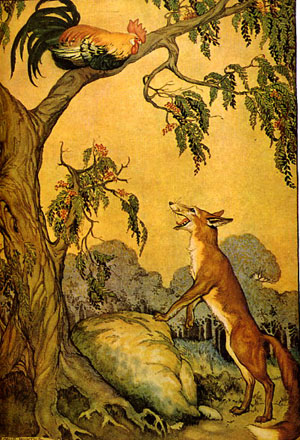

In Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales (1392), the “Nun’s Priest’s Tale” is set Syn March bigan thritty dayes and two. Modern scholars believe that there is a copying error in the extant manuscripts and that Chaucer actually wrote, Syn March was gon. Thus, the passage originally meant 32 days after April, i.e. May 2, the anniversary of the engagement of King Richard II of England to Anne of Bohemia, which took place in 1381. Readers apparently misunderstood this line to mean “March 32”, i.e. April 1. In Chaucer’s tale, the vain rooster Chaunticleer is tricked by a fox.

The Roman celebration of Hilaria on the eighth day before the Kalends of April—March 25—in honour of Cybele, the mother of the gods; the day of its celebration was the first after the vernal equinox, or the first day of the year which was longer than the night. The winter with its gloom had died, and the first day of a better season was spent in rejoicings. All kinds of games and amusements were allowed on this day; masquerades were the most prominent among them, and everyone might, in his disguise, imitate whomsoever he liked, and even magistrates.

For another “take” on April Fools’ Day, read the article here.