And I saw Heaven wide open, and behold, a white horse; its rider’s name was Faithful and True and in righteousness he judges and makes war…. he was clothed in a cloak dipped in blood , and he was called the Word of God. (Apoc. 19:11, 13)

Christ, the Word of God, rides into battle and emerges victorious. The Word of God, the Logos, is the divine blueprint for the universe while the Wisdom of God is the practical application of that blueprint.

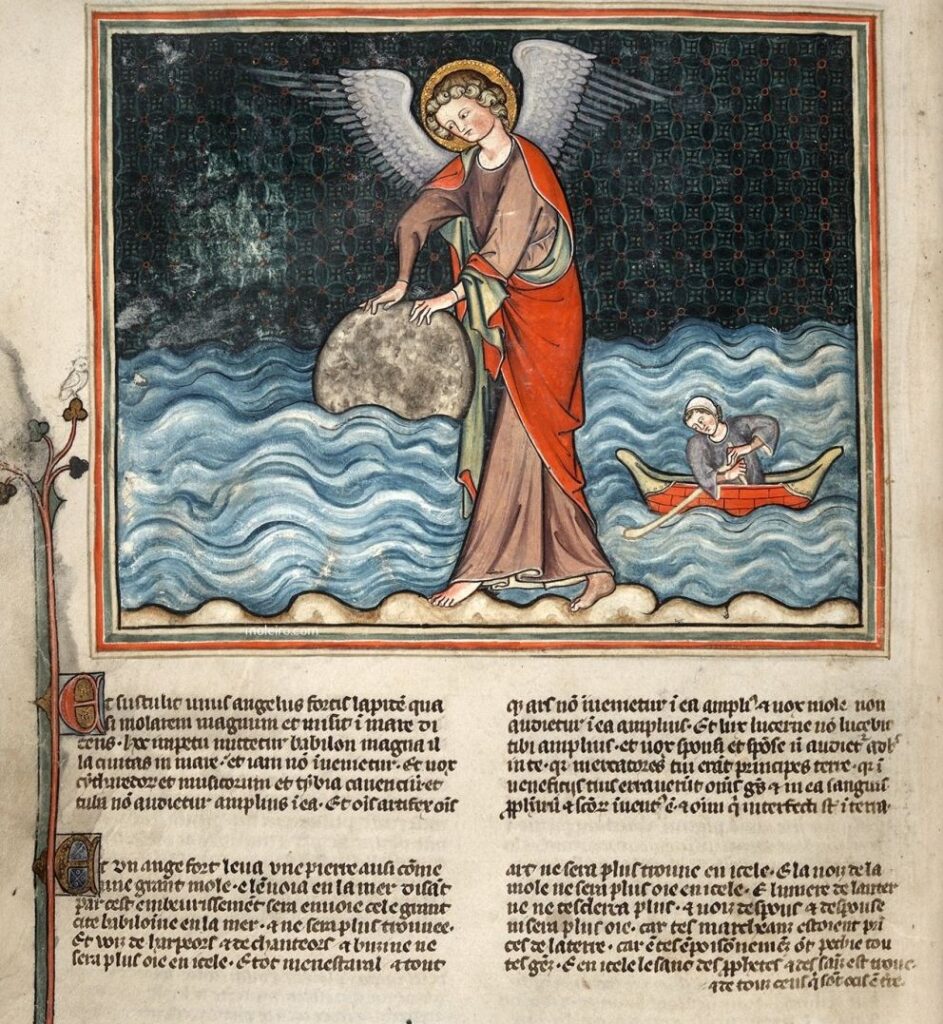

The New Testament tells us that the Word was made flesh (John 1:14) and the Old Testament tells us that Wisdom leaped down from the heavenly throne in the middle of the night to save the Hebrews in Egypt. This image of Wisdom coming to earth at midnight (Wisdom 18) to slay the enemies of Israel was first used by the Church to describe Christ’s descent into Hell and his Resurrection during the night between Holy Saturday and Easter morning but then the image of Wisdom’s descent to earth at midnight also suggested the birth of Christ at Bethlehem and eventually resulted in our celebrations of “Midnight Mass” on Christmas Eve.

The Word was made flesh. Wisdom came to earth. To say that “Wisdom built herself a house” on earth is the poetic equivalent of saying “The Word was made flesh and dwelt among us.” (Pope St. Leo the Great, Tome 2) The victory of the Word over the enemies of God is the victory of Wisdom over the enemies of God.

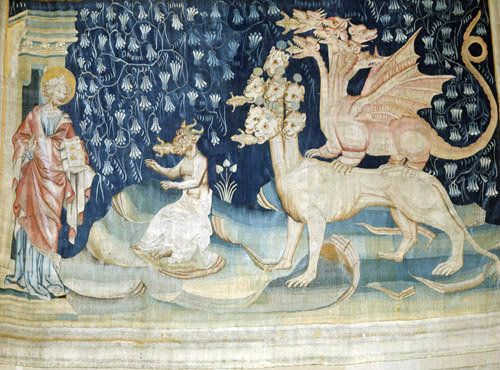

Christ is the Wisdom of God made flesh but because Wisdom—“Sophia” as she is identified in the oldest manuscripts of Proverbs—is a woman’s name, Wisdom has also been considered an allusion to Christ’s most pure Mother, the ever-blessed Virgin Mary. The victory of the Word-Wisdom is also the victory of the Mother of God, the Second Eve, treading on the head of the serpent that overcame the first Eve. Our Lady of Victory, although a feast to commemorate a victory over the Turks, is also an allusion to the victorious Mother of God who shares in the victory of her Son. She makes her Son’s victory possible by giving him flesh in her womb.