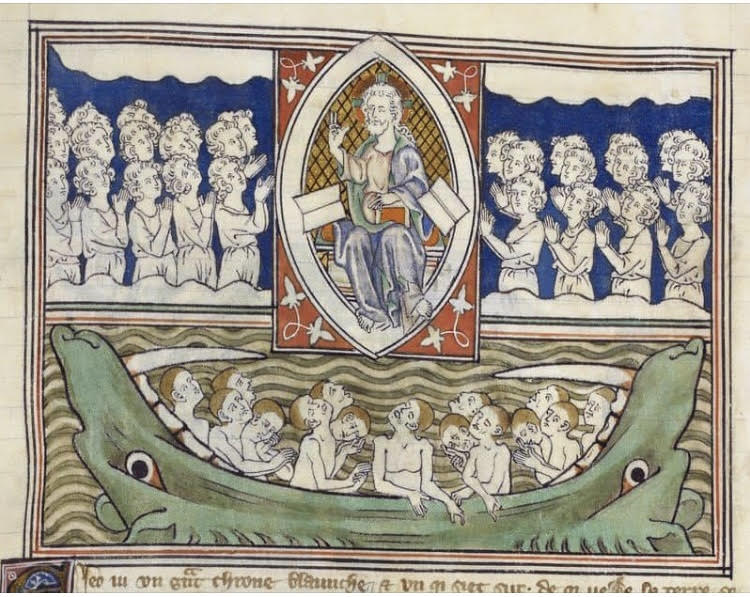

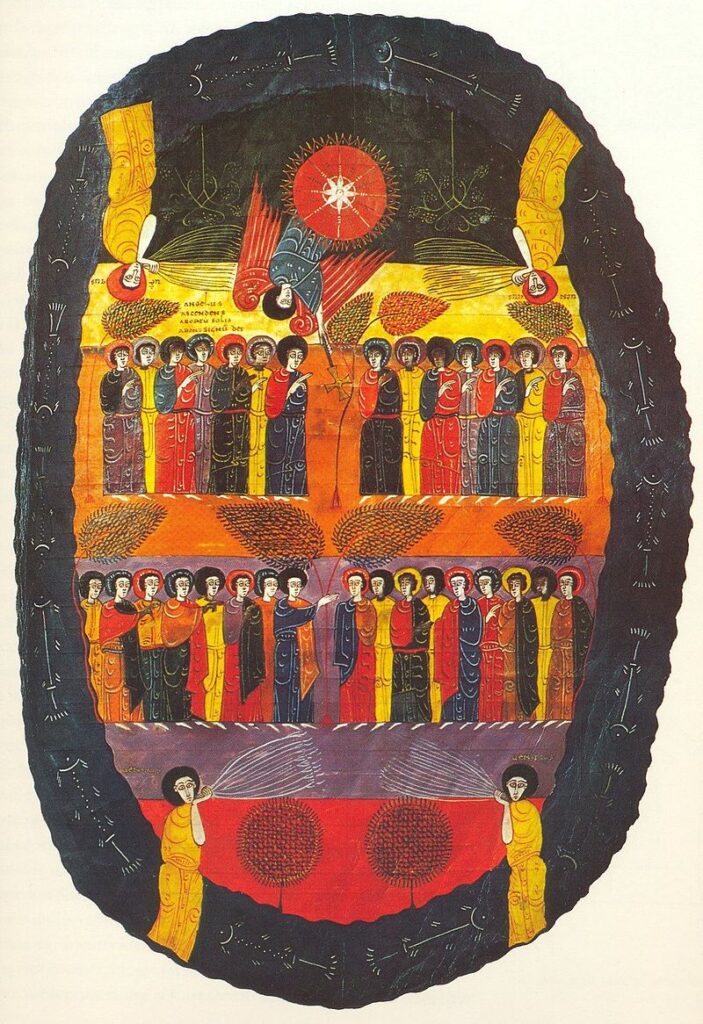

Then I saw another portent in heaven, great and astonishing: seven angels with seven plagues…. and I saw, as it were, a sea of glass mingled with fire and, standing beside the sea of glass and holding harps of God, were those who had been victorious against the beast and its image and the number of its name. (Apocalypse 15:1-2)

St. John sees another seven angels ready to unleash another seven plagues on the earth and then he sees the victorious martyrs standing beside a sea of glass and fire, holding harps and singing “the song of Moses, the servant of God, and the song of the Lamb.” (Apoc. 15:3)

We have encountered the sea of glass in Apoc. 4 — here it is described as a molten mix of glass and fire. This sea is an allusion to the Red Sea which was deliverance for the Israelites and doom for the Egyptians. Here, the victorious sing “the song of Moses” which is no vindictive triumph over enemies but solely a song of praise to the Lord and King.

St. Andrew of Caesarea thinks

The sea of glass is both the multitude of those being saved and the future condition–the brilliance of the saints-, who will shine by means of their sparkling virtue…. the fire will both burn the sinners and illuminate the righteous. Fire is both divine knowledge and the life-giving Spirit–for in fire God was seen by Moses and the Spirit descended upon the apostles as tongues of fire–and the harps indicate the mortification of members (Col. 3:5), the harmonious life of a symphony of virtues plucked by the musical pick (plectrum) of the divine Spirit. (Chapter 45, “Commentary on the Apocalypse”)

The sea is both salvation and condemnation, just as the incense in the bowls held by the angels:

We are the sweet fragrance of Christ among those who are being saved and among those who are perishing: indeed, to some the fragrance of life and to others the stench of death. (2 Cor. 2:15-16)

Tyconius, in his classic commentary on the Apocalypse, points out that the prayers of the saints–the incense offered by the angels, an allusion to the liturgical intercessions of the Church on earth–lead to both the salvation of the world and the condemnation of the fallen order.

As with so much in the Apocalypse–as in life–the same events or experiences can lead to either salvation or damnation. How do we choose to react to these events?

The choice is ours.