Brothers and sisters, as an example of patience in the face of suffering, take the prophets who spoke in the name of the Lord. You know, we count as blessed those who have persevered. You have heard of Job’s perseverance and have seen what the Lord finally brought about. The Lord is full of compassion and mercy. (James 5:10-11)

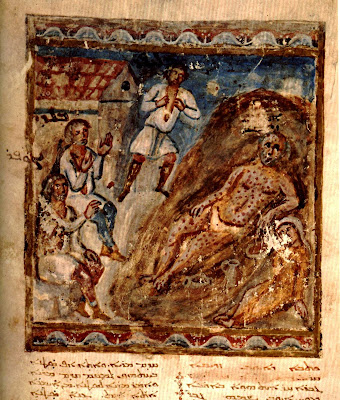

The figure of Job in the Old Testament has commonly been considered a prophet for most of Christian history because of his stalwart preaching to his friends during the afflictions he suffered and because he was thought to be a type–a prefiguration–of Christ because of his patient, innocent endurance. In the version of the Old Testament that James and his audience knew, the conclusion of the book of Job reads:

“And it is written that he will rise again with those whom the Lord raises up.

“This man is described in the Syriac book as dwelling in the land of Ausis, on the borders of Idumea and Arabia; and his name before was Jobab; and having taken an Arabian wife, he begat a son whose name was Ennon. He himself was the son of his father Zara, a son of the sons of Esau, and of his mother Bosorrha, so that he was the fifth from Abraham. And these were the kings who reigned in Edom, which country he also ruled over. First Balak the son of Beor, and the name of his city was Dennaba. After Balak, Jobab, who is called Job….”

(Job 42, LXX)

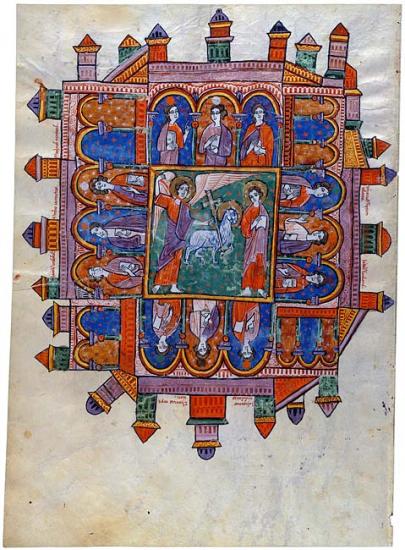

Job not only endured his unjust suffering patiently, he was expected to be among the just who would be raised on the Last Day. His suffering and promised resurrection were both seen by early Christians as pointing to the innocent suffering and promised resurrection of Christ as well as the innocent suffering of the early Christian community and the resurrection they expected to share as well at the Last Day. (It is this version of the conclusion of the Book of Job that is read on Good Friday afternoon by Eastern Christians each year.)

Patiently enduring undeserved suffering and affliction is one of the major themes of the epistle of James. Various sins–pride, hypocrisy, favoritism, slander–only bring more suffering to the community. James urges his readers to live with humility and godly–not secular–wisdom. Prayer is an essential part of this, James tells his readers.

Patience and humility are the direct result of the prayerful expectation of the coming Resurrection. Knowing they will be raised, James’ readers are able to see their experiences from a different perspective and in another light than those who think their deaths will mean the end of their existence. Expecting the resurrection, James’ readers no longer need to fear death and because they do not fear death, they can endure suffering with patient prayerful endurance. They can be like the prophet Job, sharing in Christ’s patient suffering and victorious resurrection.