“Who is she that goes up from the desert, as a pillar of smoke of aromatic spices–of myrrh and frankincense and all the perfumer’s powders?” (Song of Songs 3:6)

The friends of the groom are surprised by what they see, St. Gregory of Nyssa tells us. They know she is beautiful more splendid than gold or silver. But now they see her ascending and are struck with amazement and compare her beauty and virtue to not just a simple, single variety of incense but to a mixture of frankincense and myrrh together.

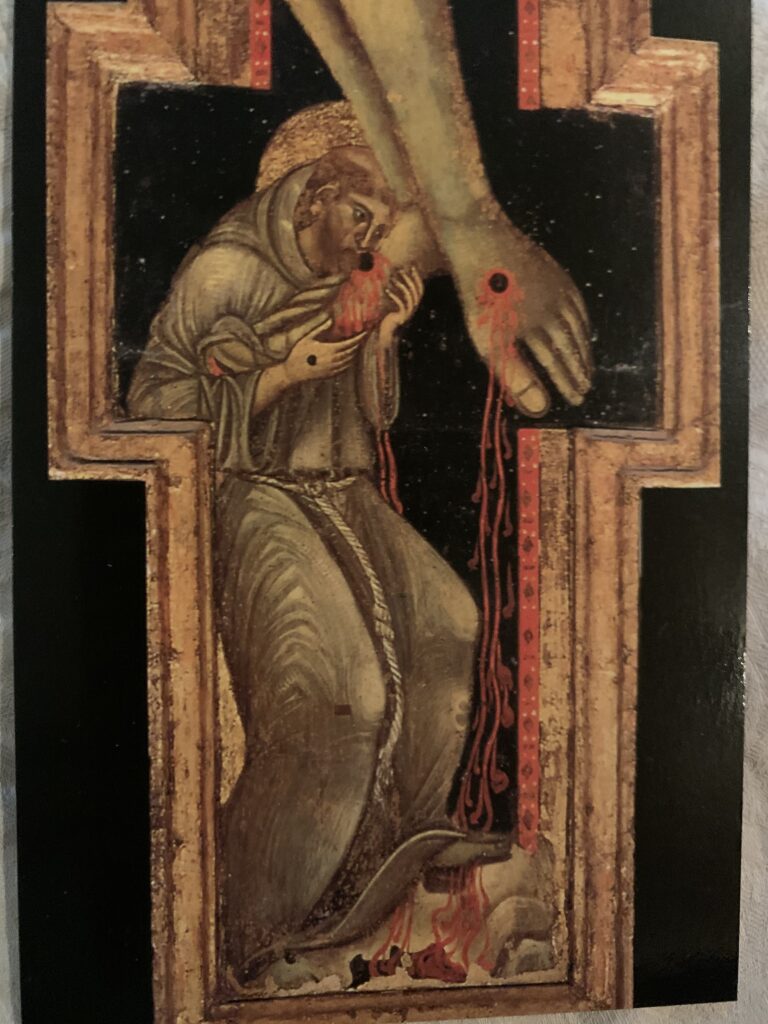

“One aspect of their praise is derived from the association of these two perfumes: myrrh is used for burying the dead and frankincense is used in divine worship…. a person must first become myrrh before being dedicated to the worship of God. That is, a person must be buried with Christ who assumed death for our sake and must mortify themselves with the myrrh–understood as repentance–which was used in the Lord’s burial.” (St. Gregory of Nyssa, On the Song of Songs)

A person must embrace ongoing self-examination and repentance; only then is it possible to then possible to enter the presence of God as the frankincense which is offered by the angels before the throne of God (Rev. 8:4).

Another of the spices used by perfumers was cinnamon. It was thought to have several remarkable properties, such as stopping putrefaction or infection and would cause a sleeping person to answer questions truthfully. So the application of “spiritual cinnamon” would stop anger, induce honest/truthful self-examination, and calm the anxious.

Myrrh and cinnamon were therefore metaphors for attitudes and practices that would protect a person from sin. In the Song, the bride–who was a type of the Mother of God–was not only myrrh and cinnamon but a protective fortress as well. The bride–in patristic sermons, the Mother of God–is a fortress with shields hanging from the battlements. The walls of the fortress are impervious to spears. The early fathers took this to mean that the prayers of the Mother of God could protect Christians from the darts and arrows of temptation. The fortress could also be seen as the Church herself, steadfast and immoveable on the rock of faith.

There were 18th century icons to illustrate this idea of the Mother of God as fortress; the inscription at the top of these icons was commonly:

“Like the Tower of David is your neck, built on courses of stone; a thousand shields hang upon it, all arrows of the mighty.” (Song of Songs 4:4)

In the example of this kind of icon seen above, the two saints appearing at the sides are additions generally not found in other versions. They are the Martyr Adrian and the Martyr Natalia. Some examples have instead the military saints such Alexander Nevsky at left, and George at right, but many have no saints added to the main image.

Much thanks to the Icons and Their Interpretation blog for information about this icon.