“How filled with bliss were these women who, taught by the angel’s account, were found worthy to announce the triumph of the resurrection to the world and to proclaim that the sovereignty of death, to which Eve became subject when she was seduced by the serpent’s speech, had been utterly destroyed! How much more blissful will be the souls of both men and women equally, when, aided by heavenly grace, they have merited to triumph over death and enter into the joy of a blessed resurrection, while the condemned have been struck with trepidation and well-deserved punishment on the day of judgment!” (excerpt from Homily II.7, St. Bede, Homilies on the Gospels, vol. 2, translated by Martin and Hurst)

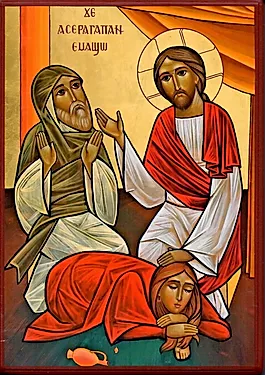

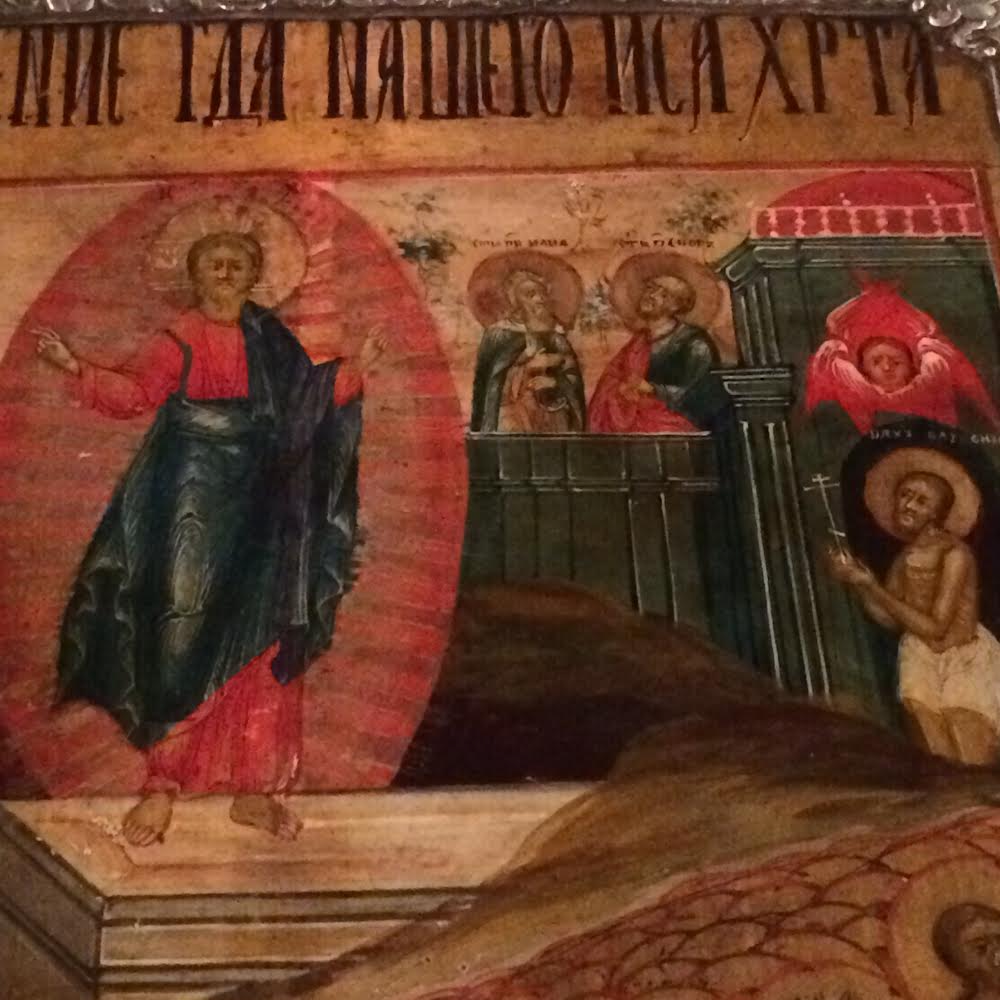

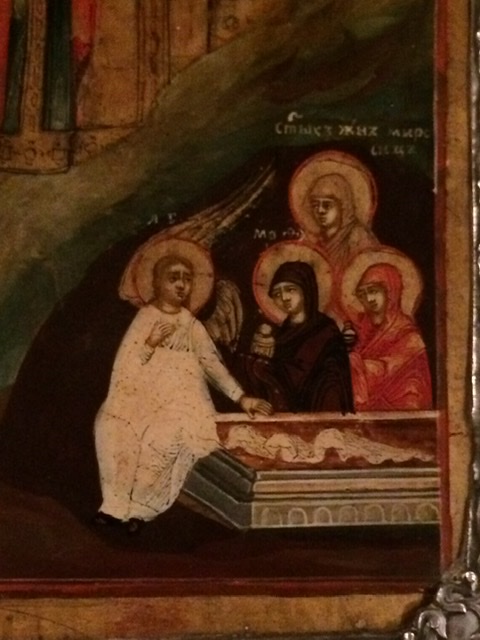

The knowledge of the gospel, the “good news,” depends on the preaching of the women who came to the tomb and discovered that Christ had risen. The angel at the tomb sent them back to preach the good news to the male apostles who were still hiding after the Crucifixion, frightened and alone. If the women had said nothing, no one would have ever heard that Christ had destroyed Death. Their participation in the divine plan of salvation was critical. All subsequent Christian experience depends on them having gone to the tomb and then telling everyone what had happened there.

We see a contrast between Eve and the Virgin Mary, the second Eve–just as Christ is the Second Adam–insofar that Eve was confronted by a (fallen) angel and chose to defy God, bringing Death into the world while the Virgin Mary was confronted by an angel (Gabriel) and chose to cooperate with God to bring true Life into the world. (Read more about this in St. Irenaeus of Lyons.) We can also see a contrast between the Myrrhbearing Women and Eve insofar that Eve hid from God in a garden and was given an apron of fig leaves to hide her nakedness while the Myrrhbearing Women stepped forward to meet the Risen Christ in a garden and were able to “put on Christ” (Galations 3:27) to remove their sinfulness.

St. Bede says something similar in another homily, where he contrasts the several Myrrhbearing Women to the one woman (Eve): “You see that several [women], instructed by the angels, proclaim that the death which one woman, seduced by the devil, had brought upon the world was now destroyed. One woman, coming [out of the garden] opened a path [that led away] from heavenly joys; many, coming back from their present exile, gave the information that the gate had now been unbarred for regaining the heavenly fatherland.” (Homily II/10, p. 94)

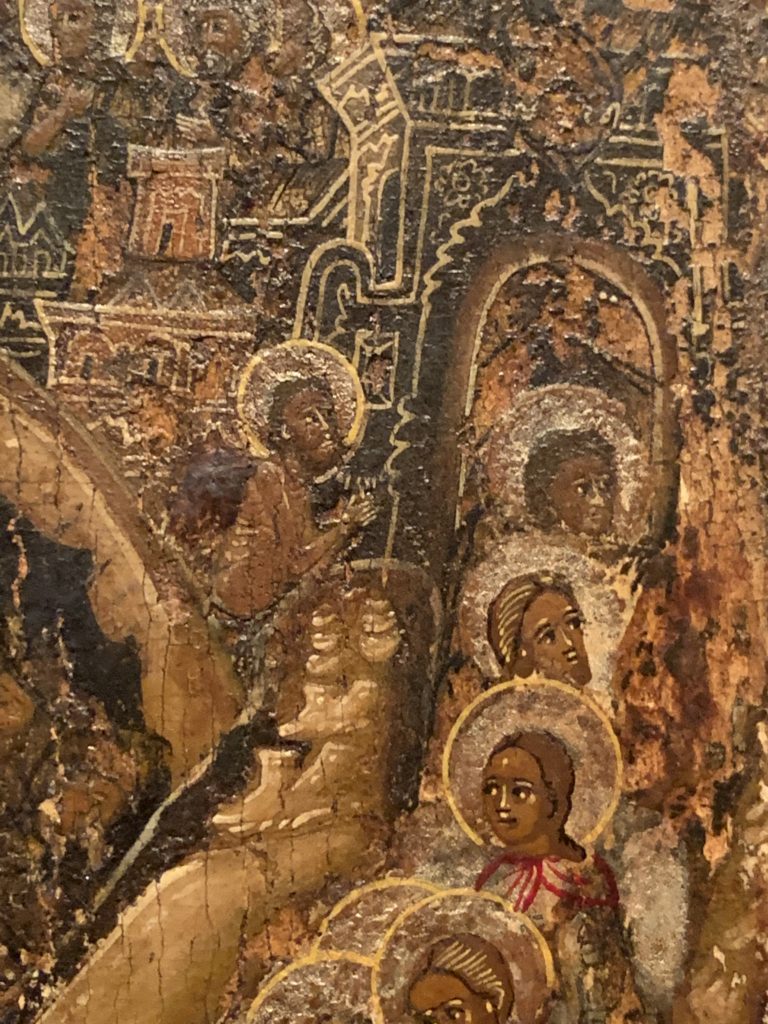

The stars of Orion’s belt in the night sky are sometimes called “the Three Marys” or “the Myrrhbearing Women;” these same stars are sometimes called “the Magi,” and identified with the Wise Men who came to visit the Christ Child. This association demonstrates the similar roles of the Myrrhbearing Women and the Magi in the Easter/Christmas stories as they were Outsiders (women and pagan philosophers) who were responsible for proclaiming the good news, the gospel, of Christ to the world.