“I love you, O Lord my strength, O Lord my stronghold, my crag, and my haven. My God, my rock, in whom I put my trust.” (Psalm 18:1-2)

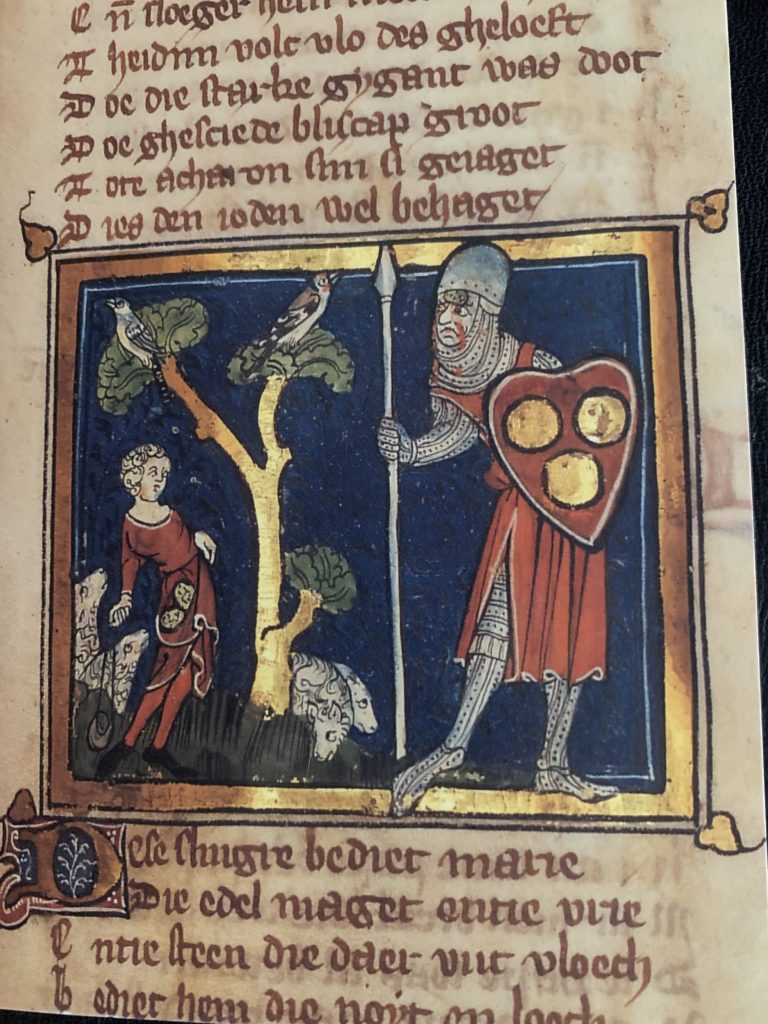

When David was a teen, before he was made king of Israel, he volunteered to fight the giant Goliath in single combat (read the Old Testament story in 1 Samuel 17). Goliath was approximately 10 feet tall, had 6 fingers on each hand, and was rumored to be descended from the giants (these details are reported in 1 Chronicles 20:6). Goliath also had bronze armor and a 19 pound iron spear, which was unusual at that time. He was a formidable opponent. But, as the well known story reports, David selected 5 stones from a riverbed and was able to kill Goliath with a stone from his slingshot. He then cut off Goliath’s head to prove his victory and sang Psalm 18 in celebration (see also the report in 2 Samuel 22).

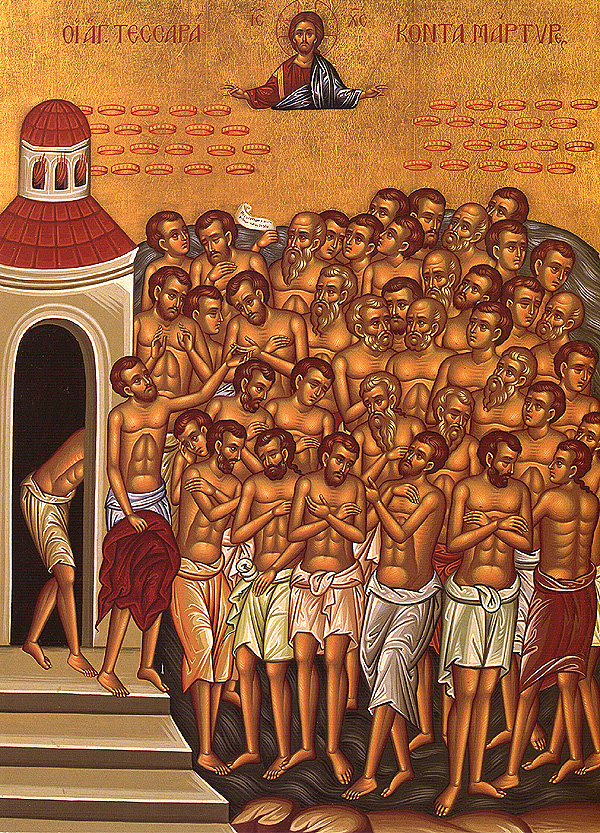

At the Kiss of Peace during the celebration of the Divine Liturgy in the Orthodox Church, the priest quietly recites the first verses of this psalm. The exchange of the Kiss, reconciling the participants and celebrating their mutual forgiveness before singing the consecration prayers and receiving Holy Communion, is like the stone David let fly from his slingshot: it slays the enemy of the People of God. The division and animosity of anger and holding grudges are among the most powerful weapons of Evil and Death; the fury and refusal to accept fellowship with others is a foretaste of Death and mutual forgiveness anticipates the Resurrection in which we experience the re-establishment of harmony between God and humanity, between God and the entire creation, between each of us with each other and the creation as well. The early preachers and teachers of the Church understood the power of the Antichrist to be precisely this division, animosity, and chaos.

Goliath is a personification of all that opposes God and His creation. The stone from David’s slingshot anticipates the Cross, the weapon by which the Enemy is slain. The Kiss of Peace reveals the power of the Cross in the live of the community assembled to celebrate the Eucharist. We are able to embrace one another, call even those who hate us “Brother!” and forgive all by the power and joy of the Resurrection. The Kiss of Peace, the stone in our slingshot in our battle with the Enemy, is more than a simple gesture or chance to greet our friends. It is one of our most effective weapons against Death and the Devil (“the divider” and “the adversary”).

During this time when we may not be able to exchange the Kiss of Peace during the liturgical celebration, it is especially important that we continue to forgive and metaphorically embrace those we may harbor animosity against. Now, more than ever, we must celebrate the Resurrection in every manner available to us.