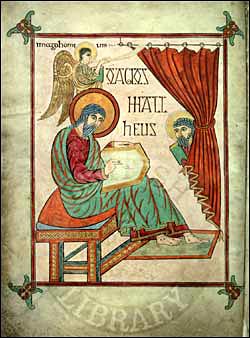

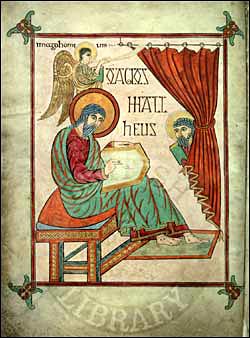

Full-page miniature of the Evangelist Saint Matthew, accompanied by his symbol, a winged man blowing a trumpet and carrying a book; folio 25v of the Lindisfarne Gospels produced about 100 years after St. Aidan founded the monastery.

St. Aidan of Lindisfarne (died 31 August AD 651) was an Irish monk and missionary credited with restoring Christianity to northern England. He founded a monastic cathedral on the island of Lindisfarne and served as its first bishop. He travelled throughout the countryside, spreading the gospel to both the Anglo-Saxon nobility and the socially disenfranchised (including children and slaves).

In the years prior to Aidan’s mission, Christianity, in northern England was being largely displaced by Anglo-Saxon paganism. However, the young king Oswald vowed to bring Christianity back to his people—an opportunity that presented itself in AD 634, when he gained the crown of Northumbria. King Oswald requested that missionaries be sent from the monastery of Iona in Scotland. At first, they sent him a bishop named Cormán, but he alienated many people by his harshness, and returned in failure to Iona reporting that the Northumbrians were too stubborn to be converted. Aidan criticized Cormán’s methods and was soon sent as his replacement. Aidan became bishop in AD 635.

Allying himself with the pious king, Aidan established a monastic community on the island of Lindisfarne, which was close to the royal castle, as the seat of his diocese. An inspired missionary, Aidan would walk from one village to another, politely conversing with the people he saw and slowly interesting them in Christianity:

“He was one to traverse both town and country on foot, never on horseback, unless compelled by some urgent necessity; and wherever in his way he saw any, either rich or poor, he invited them, if infidels, to embrace the mystery of the faith or if they were believers, to strengthen them in the faith, and to stir them up by words and actions to alms and good works. … This [the reading of scriptures and psalms, and meditation upon holy truths] was the daily employment of himself and all that were with him, wheresoever they went; and if it happened, which was but seldom, that he was invited to eat with the king, he went with one or two clerks, and having taken a small repast, made haste to be gone with them, either to read or write. At that time, many religious men and women, stirred up by his example, adopted the custom of fasting on Wednesdays and Fridays, till the ninth hour, throughout the year, except during the fifty days after Easter. He never gave money to the powerful men of the world, but only meat, if he happened to entertain them; and, on the contrary, whatsoever gifts of money he received from the rich, he either distributed them, as has been said, to the use of the poor, or bestowed them in ransoming such as had been wrong fully sold for slaves. Moreover, he afterwards made many of those he had ransomed his disciples, and after having taught and instructed them, advanced them to the order of priesthood.” (Venerable Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation. Book III: Chapter V)

His pastoral emphasis on prayer, fasting, Christian education and his own personal humility is similar to all the famous pastors such as St. John of Kronstadt and the Cure d’Ars.

There are four wells associated with St. Aidan which are said to work miracles of healing, especially of asthma and skin diseases.

He is known as the Apostle of Northumbria and is recognised as a saint by the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Catholic Church, and the Anglican Communion.