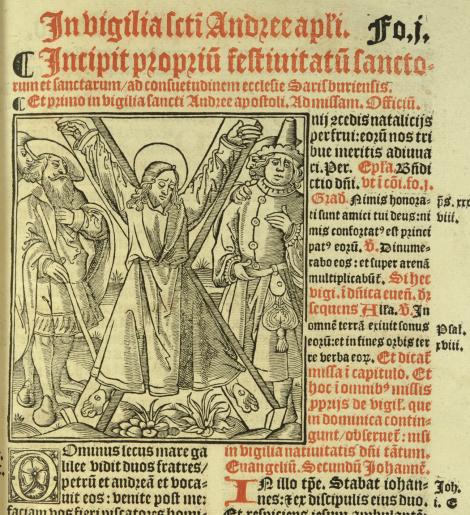

Woodcut of the martyrdom of St Andrew from a Sarum Missal printed in Paris in 1534.

Every year on November 30, Scotland celebrates the feast day of its patron saint, St. Andrew. The day is celebrated and commemorated with festivities, parades, traditional Scottish music and dancing. By law, all buildings in Scotland are required to display the Scottish National Flag that bears the image of the Saltire, or St Andrew’s Cross.

But… St. Andrew was not Scottish. In fact, the saint was born in Bethsaida, Israel. Moreover, St. Andrew never stepped foot in Scotland. Although St. Andrew was strongly associated with Scotland from around AD 1000, he only became the official patron saint of Scotland in AD 1320. (St. Andrew is also the patron saint of Greece, Russia, the Amalfi region of Italy, and Barbados.)

According to folklore, St. Andrew requested to be tied to an X-shaped cross, as he believed he was ”not worthy of dying in the same shape of a cross as Jesus”. Since the year 1385, this X-shape represents the white cross displayed on the Scottish flag. A notable feature of the small town in Scotland named for St. Andrew is the University of St Andrew. Founded in 1413, this is the oldest university in Scotland, as well as being the third oldest university in the English-speaking world. The university is known worldwide for teaching and research. The University was the first Scottish university to allow women to enroll as undergraduates (1892).

Regarded as ”one of the world’s greatest small universities”, the university is heavily interlinked with the town as students of the university making up roughly 1/3 of the population (under 20,000).

In Romania, where St. Andrew is also the patron saint, a number of traditions and rituals surround the apostle. On the morning of St Andrew’s day, mothers gather up tree branches and make a bunch for each family member; the person whose bunch blooms by New Year’s Day will have good luck and health that year. It is also said girls should put a branch of sweet basil – or 41 grains of wheat – under their pillow on the night of St Andrew’s Day. If they dream someone takes them, it means they will marry soon.

St Andrew is also linked to superstition and custom surrounding matrimony in several other countries. Reports suggest that in parts of Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovakia, names of potential husbands are written on pieces of paper and stuffed in pieces of dough. After baking, the first one to rise to the top when put in a bowl of water would reveal the name of their future husband.

You can find more legends of St. Andrew here.