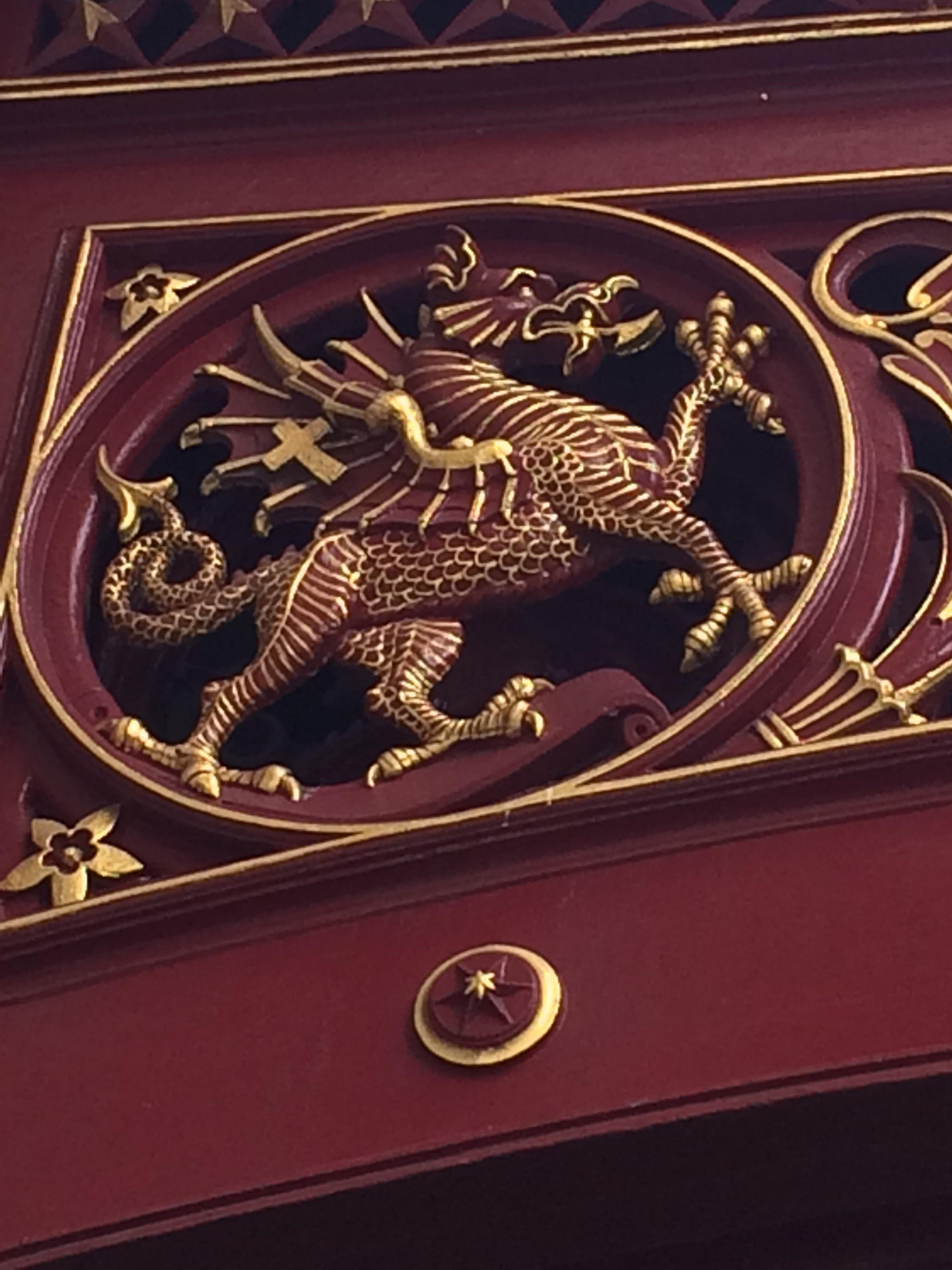

Sword rest in St. Magnus the Martyr Church, London. (photo by S. Morris)

Sword rests, or sword stands as they are sometimes called, were originally installed in the churches of London to hold the Lord Mayor’s sword-of-state when he visited a different church every Sunday–a practice which ceased in 1883.

This practice of setting aside the sword was rooted in a medieval practice of men setting their swords in a prominent place in church so that no fighting would erupt during Mass. The swords were all kept up front so that no one could secretly get theirs to start a fight or secretly steal someone else’s as they slipped out the door. Churches were considered sanctuary spaces where fighting was forbidden. If blood was spilled in a church it had to be torn down and rebuilt. Or it had to be at least re-consecrated with a complicated–and expensive–process of prayer and ritual. Truces between enemies were automatic if they were in a church together.

The Kiss of Peace, exchanged between members of the Church just before receiving Holy Communion, was thought to be the most important act in preparation for Communion. St. Augustine, for example, speaks of it in one of his Easter Sermons:

“Then, after the consecration of the Holy Sacrifice of God, because He wished us also to be His sacrifice, a fact which was made clear when the Holy Sacrifice was first instituted, and because that Sacrifice is a sign of what we are, behold, when the Sacrifice is finished, we say the Lord’s Prayer which you have received and recited. After this, the ‘Peace be with you’ is said, and the Christians embrace one another with the holy kiss. This is a sign of peace; as the lips indicate, let peace be made in your conscience, that is, when your lips draw near to those of your brother, do not let your heart withdraw from his. Hence, these [the Kiss itself as well as Holy Communion] are great and powerful sacraments.”

Hence, the sword rest is an objective witness to the Kiss of Peace and its importance in the life of the community.