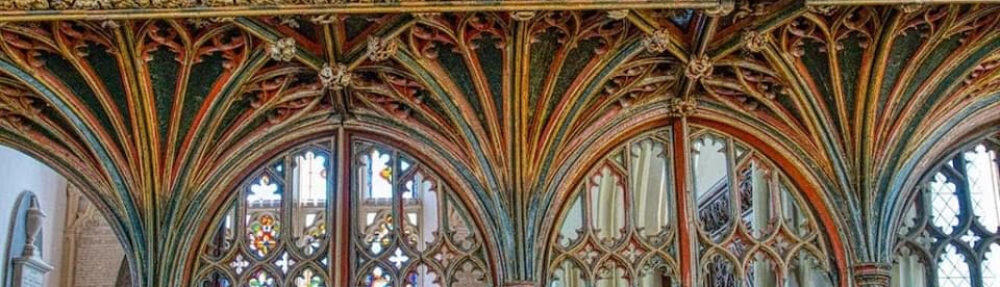

The Roman Catholic and Orthodox churches commemorate of the Beheading of St. John the Baptist on August 29. However, in Italian folklore the story of the daughter of Herodias became attached to June 23, St John’s Eve, which is the night before the Feast Day of St. John the Baptist, June 24. (Usually, a feast day of a saint commemorated the death of that saint to celebrate her/his martyrdom; the feast of St. John the Baptist is one of the very few saints’ days to mark the anniversary of a saint’s birth. Click here for my earlier post about St. John’s Nativity and Midsummmer. Click here for another post about Midsummer and St. John’s Wort.) In Rome, youths would gather in front of the cathedral of Basilica of St. John Lateran on the night of June 23, because Herodias traveled in the air.

“Salome of the Seven Veils” is the name by which the “daughter of Herodias” is generally known in modern American culture. J.B. Andrews in his 1897 folklore article (Neapolian Witchcraft, Folklore Transactions of the Folklore Society, Vol III March, 1897 No.1) wrote:

It is believed that at midnight then [St. John Baptist’s Eve, June 23] Herodiade may be seen in the sky seated across a ray of fire, saying:

” Mamma, mamma, perche` lo dicesti?”

“Figlia, figlia, perche’ lo facesti? “

“Herodiade” or “Erodiade” is the Italian version of the name Herodias.

Sabina Magliocco in her incredible article Who Was Aradia? The History and Development of a Legend, The Pomegranate (see The Journal of Pagan Studies, Issue 18, Feb. 2002) explained what Herodiade was doing in the airs on June 23, the Eve of St. John Baptist’s Feast Day:

According Sabina Magliocco, there was an early Christian legend or folklore derived from the bibical account (Matthew 14:3-11, Mark 6:17-28) of Herodias and Herodias’ daughter. When the head of the saint was brought forth on a platter, she-who-danced-for-the-head-of-the-Baptist had a fit of remorse, weeping and bemoaning her sin. A powerful wind began to blow forth from the saint’s mouth, so strong that it blew the famous dancer up into the air, where she is condemned to wander.

Titus Flavius Josephus, a first-century Jewish historian provides the name of stepdaughter and niece of Herod Antipas as Salome, but Josephus makes no mention of the infamous dance. Josephus in his Antiquities of the Jews recounted that after the excution of John that Herod, Herodias, and her daughter Salome were exiled Lugdunum, near Spain.

However, the name “Salome” does not appear in the biblical accounts of the beheading of John the Baptist. In the Latin Vulgate Version, the girl is refered to as the “daughter of the said Herodias.”

At some point, the “daughter of Herodias” and “Herodias” became conflated in folklore in early medieval Europe.

Probably because the holiday of St John the Baptist was widely celebrated during the Middle Ages, a great deal of religious folklore surrounds Herodias. Magliocco also explained:

Diana in the Canon Episcopi, a document attributed to the Council of Ancyra in 314 CE, but probably a much later forgery, since the earliest written record of it appears around 872 CE (Caro Baroja, 1961:62). Regino, Abbot of Pr¸m, writing in 899 CE, cites the Canon, telling bishops to warn their flocks against the false beliefs of women who think they follow “Diana the pagan goddess, or Herodias” on their night-time travels. These women believed they rode out on the backs of animals over long distances, following the orders of their mistress who called them to service on certain appointed nights. Three centuries later, Ugo da San Vittore, a 12th century Italian abbot, refers to women who believe they go out at night riding on the backs of animals with “Erodiade,” whom he conflates with Diana and Minerva (Bonomo, 1959:18-19).

Eventually there developed a widespread belief that Herodias was a the supernatural leader of a supposed cult of witches, apparently asociated with or synonymous with the legendary witch-queens Diana, Holda, Abundia, and many others. In Italy, Raterius of Liegi, Bishop of Veronia in the 9th century c.e. complained that many folk believed that Herodias was a queen or goddess and that they also claimed a third of the earth was under the dominion of Herodias. Herodias was supposed to preside over the night assembly or night flight.

In parts of Italy, the dew formed on St. John’s Eve was often said to represent the tears of the daughter of Herodias. This dew was believed to have healing virtues and promote fecundity. June 23 was also known as la notte delle streghe. It was once customary in Rome to build bonfires outside the Basilica of St. John Lateran in anticipation of the night flight led by Herodias. (Read my previous post on the bonfires of June 23 here.)