An opal could bring either good fortune or death, as it was a source of liminal power that never left unaltered the person who wore it.

The name opal is derived from the Sanskrit word “upala,” as well as the Latin “opalus,” meaning “precious stone.” Opal is a gemstone of much variety; the ancient Roman natural historian Pliny once described it in the following way:

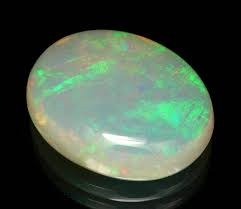

“… it is made up of the glories of the most precious stones. To describe it is a matter of inexpressive difficulty: There is in it the gentler fire of the ruby, the brilliant purple of the amethyst, the sea-green of the emerald, all shining together in an incredible union.”

To ancient Romans, the opal was a symbol of love and hope. Orientals called it the “anchor of hope.” Arabs say it fell from the heavens in flashes of lightning. It was believed to make its wearer invisible, hence the opal was the talisman of thieves and spies.

During the Medieval period, a change in color intensity of an opal was believed to indicated if its wearer was ill or in good health. The opal was supposed to maintain a strong heart, prevent fainting, protect against infection, and cleanse foul-smelling air. The stone, as in ancient times, was still regarded as a symbol of hope.

But the opal’s reputation changed in the mid-14th century. The Black Death swept across Europe, killing one quarter of its population. The gem was believed to be the cause of death. When worn by someone struck with the deadly plague, it would appear brilliant only until the person died. Then it would change in appearance, losing its luster. In reality, it was the sensitivity of this stone to changes in temperature that altered its appearance, as the heat from a burning fever gave way to the chill of death.

In Elizabethan England, the opal was treasured for its beauty. Shakespeare wrote of it in the Twelfth Night as the “queen of gems.” Queen Victoria presented her children with opal jewelry, thus making the stone popular. But the stone continued to have a mixed reputation, chiefly due to a novel written by Sir Walter Scott in 1887 that depicted it as a stone of evil.