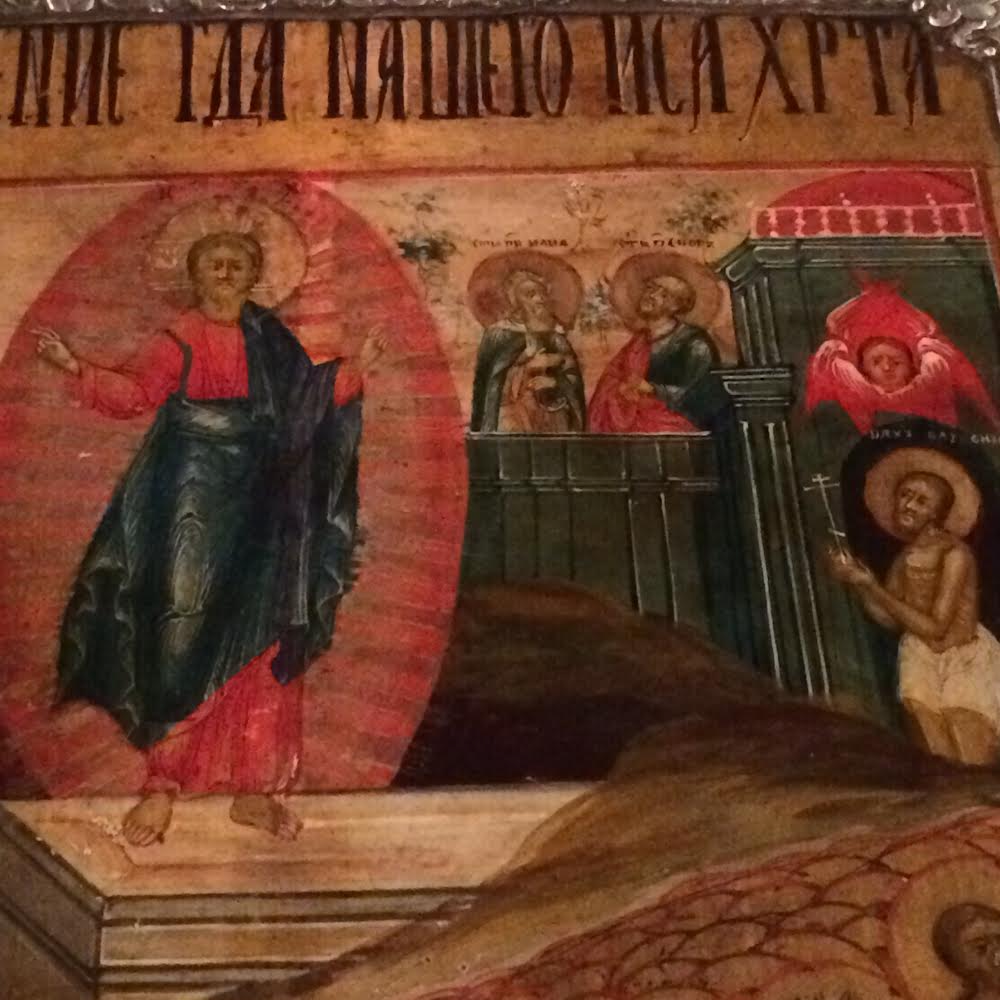

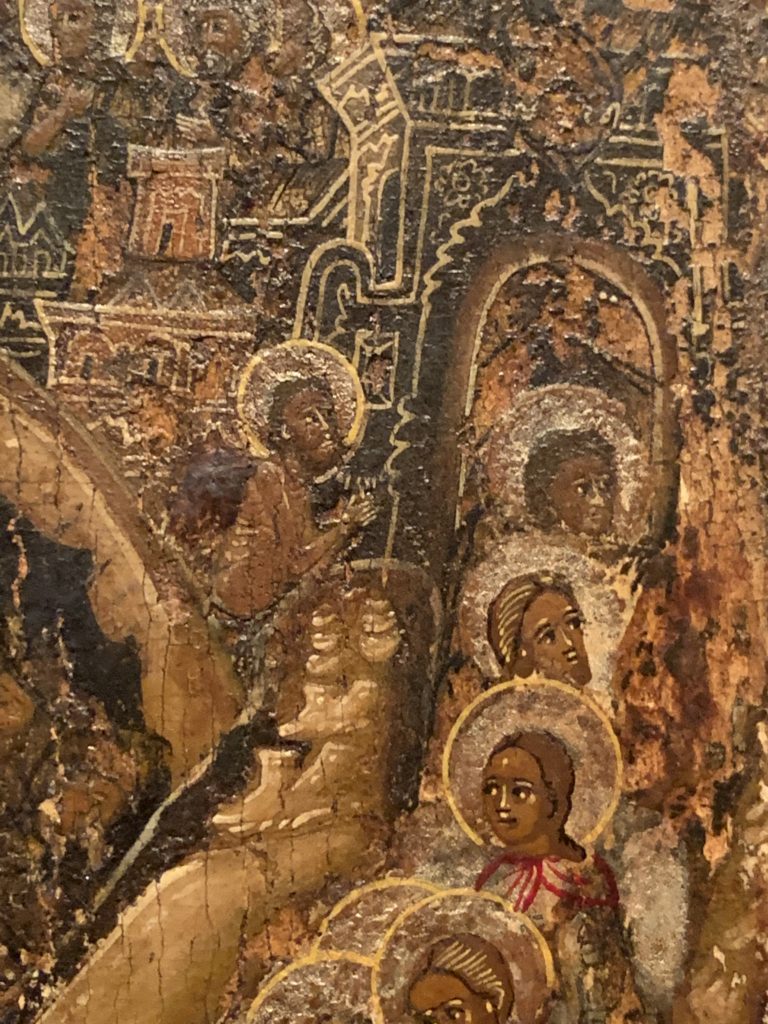

These two Russian icons from the 18th-19th centuries depict Dismas, the “Good” Thief, as he stands about to be the first to enter the newly-opened gates of Paradise. In the top image, he is carrying the cross on which Jesus was crucified which is his “passport” that proves to the angels guarding the gates that they should allow him to enter. (We also see the prophets Enoch and Elijah inside the walls of Paradise, as they are the two Old Testament figures who never died.)

In the gospel of St. Luke, one of the thieves crucified with Christ rebukes the other thief for mocking Christ: “We deserve the punishment we have received. He has done nothing to deserve this!” This penitent thief then begs Jesus, “Lord, remember me when you come in your kingdom!” Jesus responds by promising this “good” thief that they will be together in Paradise that very day. (This episode was understood by many early Christian preachers to reverse Adam’s expulsion from Paradise, which was also understood to have happened on a Friday afternoon after Adam had become a thief by stealing the fruit from the Tree of Knowledge. The good thief was also praised because he admitted his fault, unlike Adam, and took responsibility for his actions.)

The penitent thief was later assigned the name Dismas in the 4th century Gospel of Nicodemus; his name “Dismas” was adapted from a Greek word meaning “sunset” or “death.” The other thief’s name is Gestas. Dismas dies shortly after Christ himself. Christ is about to descend into Hell to liberate the captives there but first sends Dismas ahead of him to Paradise. (Dismas is called a pioneer in some sermons because he was the first to enter Paradise.)

Early Christian preachers and teachers saw Dismas as one of them, a Christian, who demonstrated Christian practices, beliefs, and virtues. Dismas was a repentant sinner. Indeed, the early preachers understood Christ’s promise –“Today you will be with me in Paradise!”–as a promise made to all repentant sinners, not just Dismas. Because this promise is made to all Christians, the plea of Dismas–“Remember me, O Lord, in your kingdom!”–became a common prayer among Christians. This cry became especially popular as a prayer before receiving Holy Communion, the celebration of the Kingdom of God already present among us.

Dismas is also seen as convert and martyr–an important role model in the time when most Christians were adult converts or faced the possibility or martyrdom for their faith. Dismas on his cross, like St. Paul on the road to Damascus, had a sudden flash of insight and understood who Christ was. Dismas, unlike St. Peter, confessed his faith in Christ when it would have been much easier to stay silent. Although he was executed for his crimes rather than his faith, Dismas was understood to be a martyr because he was a witness (martyr in Greek) for the truth of Christ’s identity who showed other Christians how to suffer under torture and die for the Truth.

Eastern Christians still use the cry of Dismas–“Remember me, O Lord, when you come in your kingdom!”–not only before Holy Communion but as a refrain when singing the Beatitudes at weekday services. Every encounter with God, whether in personal or liturgical prayer or when serving the poor/hungry/sick/needy, is a chance to experience the Kingdom of God here and now. Dismas shows us all how to recognize God in unlikely or unexpected places and to jump at the opportunity to repent, to turn our lives around, in order to be with Him.

Interested in reading more about Dismas? I heartily recommend As the Bandit Will I Confess You: Luke 23:39-43 in Eary Christian Interpretation by Mark Glen Bilby.

I already say the prayer of St. Thomas, “My Lord, and My God” at the elevation of the elements, and the prayer of the centurion, “Lord, I am not worthy that thou shouldest come under my roof, but speak the word only and my soul shall be healed” after the priest’s communion. Now I can say the prayer of St. Dismas, “Remember me, O Lord, when you come in your kingdom!” Thank you.

Dear Carter: The prayer of St. Dismas works well as part of our “spiritual communion” during these times of online celebrations of the Eucharist. We can all look forward to saying it together when we are able to gather again in person. –Stephen