Don’t you know that a little yeast leavens the entire mound of dough? Get rid of the old yeast so that you may be a new mound of dough, because you are unleavened; for Christ, our passover, was sacrificed. Hence let us celebrate not with the old yeast, not with the yeast of evil and sexual immorality, but with the unleavened bread of sincerity and truth. (1 Cor. 5:6-8)

The apostle Paul urges the Corinthians to expel the man who has a sexual relationship with his stepmother before his immoral behavior spreads and destroys them all. No one’s behavior is “private,” even if it is something a person does when no one else is there to watch.

The apostle mentions the passover sacrifice and the passover bread because the Passover feast was about to be celebrated (1 Cor. 16:8). He compares the man’s bad behavior to the yeast that must be thrown away before Passover starts. He urges the parish to not be contaminated by the man’s immoral behavior when they celebrate Passover; the apostle wants them to celebrate with the new bread of sincerity and truth, unspoilt by the “yeast” of insincerity, dishonesty, and lies.

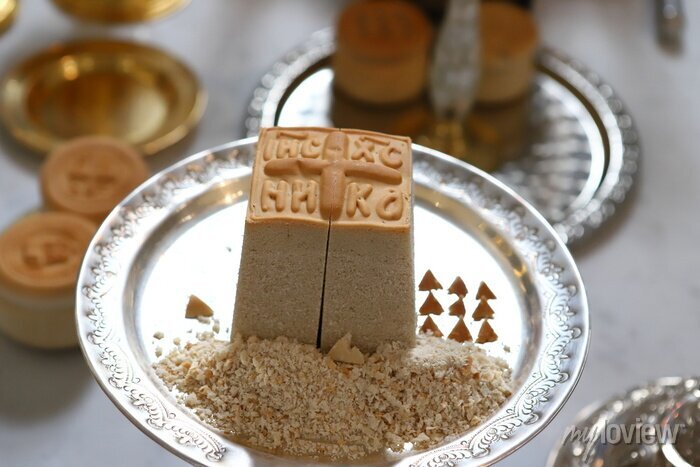

According to Jewish practice, bread without yeast would only be used once a year–i.e. during the Passover. When the first Christians–who were Jewish Christians–would have known that and would have used leavened bread for the weekly celebrations of the Eucharist. Eastern Christians still maintain the practice of using bread with yeast for the Eucharist. Western Christians also used bread with yeast but began to use bread without yeast sometime in the 10th century.

The Eastern Christians saw the yeast in the bread that they used as a sign of the Resurrection; they could not understand bread without yeast as anything except a denial of the Resurrection. They also saw the use of bread without yeast as the rejection of the 4th Ecumenical Council at Chalcedon as the Armenians, who rejected Chalcedon, also used bread without yeast in the Eucharist.

Yeast gives life to dough that is totally dead–grain harvested, ground into flour, pounded and kneaded, passed through fire. Yeast can mean resurrection.

Yeast gives life to grape juice that is also totally dead–cut from the vine and harvested, crushed beneath feet, dead. The yeast makes the grape juice come alive and ferments it, making it wine.

But if there is too much yeast or the fermentation goes on too long the wine goes sour. It becomes vinegar. The bread can grow mold. Too much yeast can make the wine and bread corrupt. Rotten. Uneatable and undrinkable. The moldy bread and sour wine must be thrown away. Yeast means Resurrection but it can also sometimes mean corruption.

See my popular 2019 blog post about Communion wafers here.