For if a woman does not cover her head, let her hair be cut; if, however, it is shameful for a woman to cut her hair or shave it off, it is better to keep her head covered…. A woman should keep her head covered because of the angels. (1 Cor. 11:6, 10)

This passage is one of the most difficult in the New Testament for modern readers to understand. St. Paul talks about women keeping silent and their heads covered all because of the angels. How can the apostle who wrote these words also have written that in Christ there is neither rich nor poor, slave or free, male or female? What is he talking about in this passage?

Hairstyles were important in 1st century Greco-Roman culture. Elite women and men spent a lot of time and money to have their hair done “properly” and even the wives of the emperors could be criticized for having an incorrect hairstyle. Men were expected to have hairstyles that were very different from women; women were expected to wear hairstyles that made it easy to see that they were not men. So the easiest and most basic way to do that was for men to cut their hair short and women to keep their hair long; a woman who cut her hair short might as well shave it all off. Philosophers spent a lot of time and ink writing about proper, appropriate hairstyles.

St. Paul wants the Christian men and women in Corinth to be recognizable as men and women. The scandal of the Cross and Resurrection should be the only hurdle making it difficult for non-Christians to embrace the Faith; upending social norms should not be a reason for non-believers to reject the Faith. But what do the angels have to do with this?

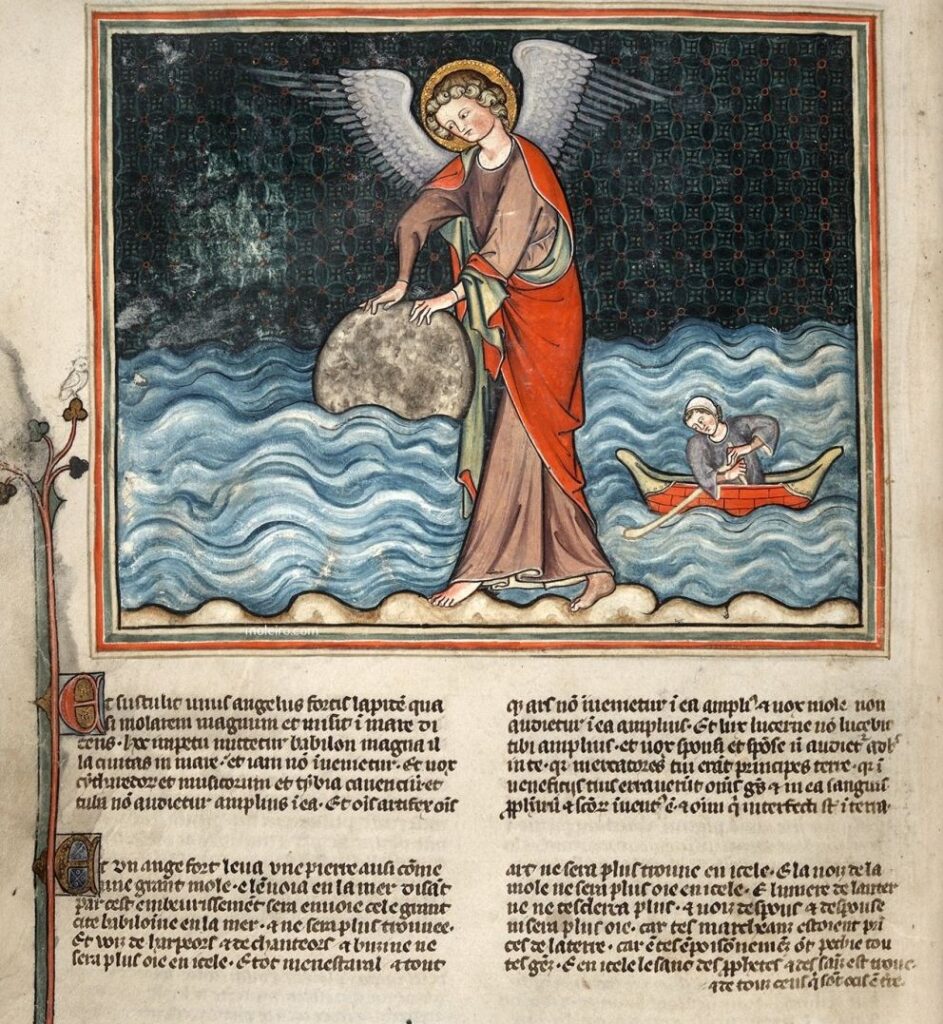

Praying and prophesying involve exposing the worshipper to the power and influence of powerful spiritual entities. Some of these are good. Some are evil. Wearing their hair like a “proper” woman was a talisman against the evil spirits that might try to deceive a woman who was praying or prophesying or interpreting Scripture (a sub-genre of prophesy). Keeping their hair long and properly coiffed was a way to protect the Christian women of Corinth, allowing only the good angels to speak to them or inspire their words.

Perhaps one reason modern readers have difficulty with this passage is because we don’t take prophesying and angels seriously any more. Understanding preaching and interpretation of scripture as acts of prophesying and acknowledging the reality, importance, and power of the angels go a long way to make a difficult passage comprehensible and not as a misogynistic rant.