Dragons are not just fairy tale creatures who like to eat an occasional princess or fight a knight or two. Dragons are mythic-poetic creatures used in tales or sermons to make sophisticated points. Perhaps rooted in early human experience of three major predators–lions, eagles, and large serpents–dragons both warn of danger and show how to escape that danger.

Although we think of dragons as fire-breathing serpents with legs and wings, the oldest stories report that dragons had a foul, poisonous breath, the stench of which could kill anything that inhaled it. Dragons are Chaos. Dragons are spiritual and emotional energy that is out of control. Unfocused. Wild. They are in stories or texts what horses with loose, untied tails are in icons.

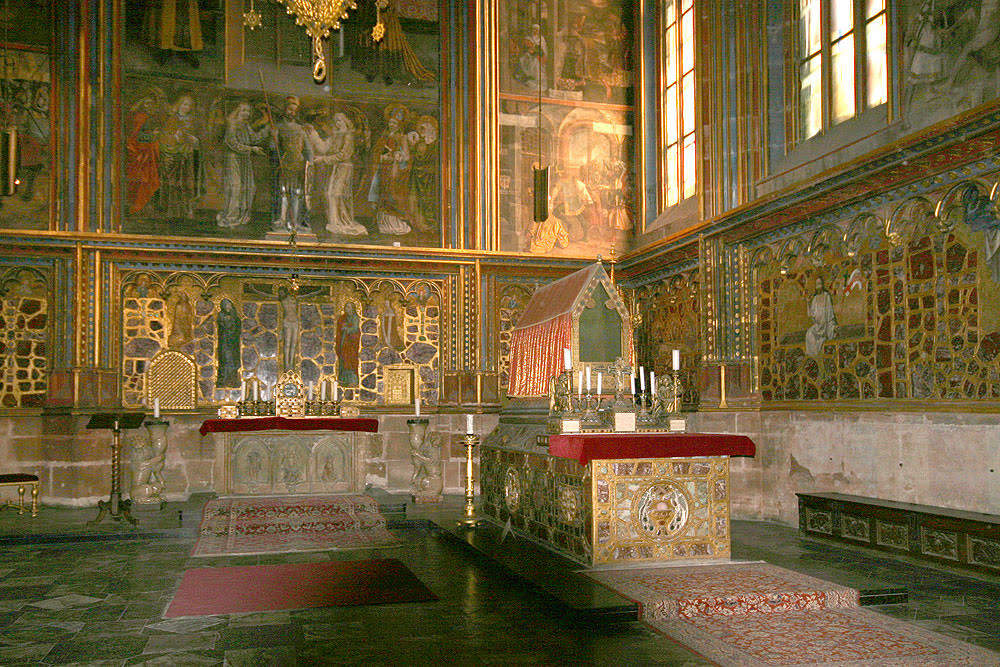

In the New Testament (Revelation 12:3) we read about a vision of a Great Red Dragon with seven heads, ten horns, seven crowns, and a massive tail, an image which is clearly inspired by the vision of the four beasts from the sea in the Book of Daniel and the Leviathan described in various Old Testament passages. This dragon is the enemy of the woman clothed with the sun, with the moon beneath her feet, and a crown of 12 stars upon her head: the Church. The dragon attacks the Church at the End of Days and slays the martyrs as Judgement Day approaches. In the lives of the saints–such as SS. Margaret or George–a dragon is the enemy of the saint or of specific persons now, during history.

In the story of St. Margaret, she is swallowed alive by a dragon in her jail cell but she makes the sign of the Cross and the dragon’s stomach explodes… allowing her to step out, unharmed. (Not unlike Red Riding Hood and her grandmother stepping unharmed from the wolf’s stomach.) In the story of St. George (whose horse’s tail is always tied in a knot), the dragon is attacking a town and is about to devour a princess as its most recent victim but George is able to kill it; in some versions, he wounds it so that it becomes a tame beast and he can lead it into the town with a leash made of the princess’ belt.

St. Margaret is clearly attacked by the enemies of God but is able to overcome them by her faith in Christ, crucified and risen. The princess (soul) is attacked by the passions–anger, jealousy, greed, etc.–but is able to either overcome them by the help of the saints and the Cross of Christ (the wooden spear of St. George). In the versions where the dragon is wounded, it means the soul is able to redirect its energy away from destructive desires into constructive desires, such as righteous anger on behalf of the oppressed, desire to care for the needy, or peace-making between enemies.

Dragons are the great enemy both at the End of Time and now, as history plays itself out. They are the spiritual energy that we can channel to come close to God or that we can let it create chaos in our lives to destroy us. We can embrace the dragon within or we can tame it. The choice is ours.