Musée National de l’Age Médiévale, Paris

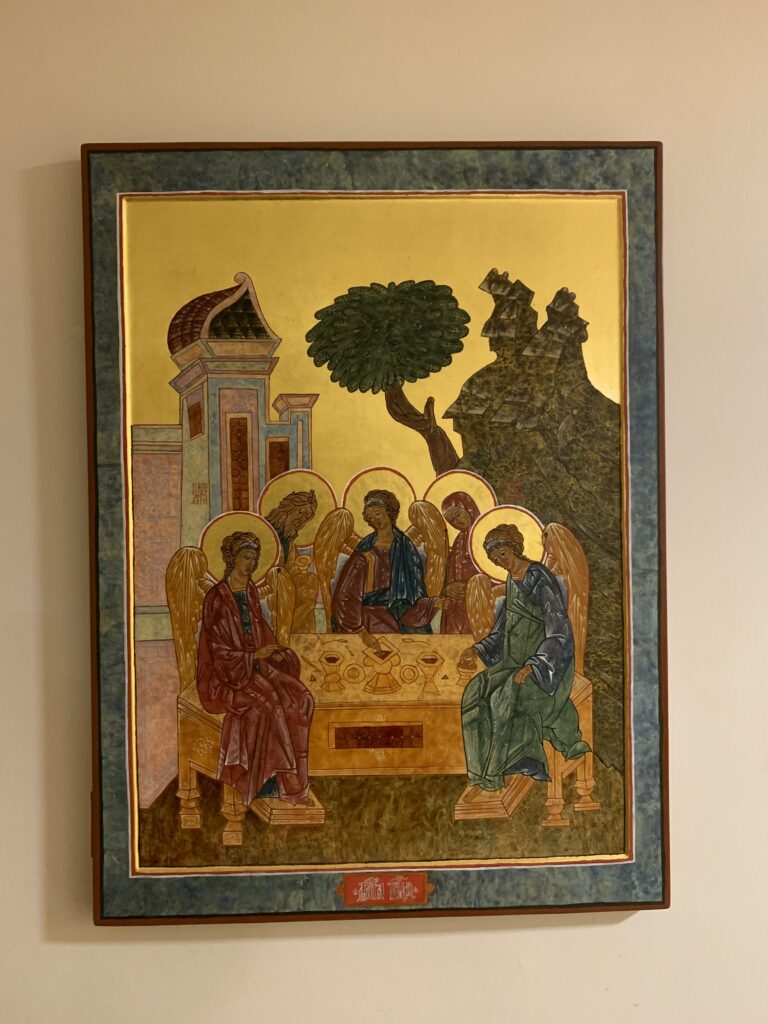

St. Benedict, identified by the inscription S[ANCTUS] BENEDICT[US] ABB[AS], “St. Benedict the Abbot.” His peaked cowl is like that seen on this saint in the 10th century fresco beneath San Crisogono in Trastevere, Rome, but with vertical and horizontal bands such as one would see on a bishop’s mitre. Benedict was not a bishop, but he is sometimes pictured in a mitre nevertheless, because a medieval abbot—and an abbess!—generally wore a mitre.

For we write you nothing but what you can read and understand; I hope you will understand fully, as you have understood in part, that you can be proud of us as we can be proud of you, on the day of the Lord Jesus. (2 Cor. 1:13-14)

St. Paul tells the Corinthians that he trusts them to understand what he is writing to them, just as they have understood what he has already taught them. He wants them to be proud of him as their spiritual father, just as he is proud of them as his spiritual children. After some of the things he said in First Corinthians, it sounds surprising that he says he is proud of them. But like any father, he is proud of his children despite their misunderstandings and problematic behavior.

Ambrosiaster, a Bible commentary writer in the AD 300s, said, “Paul asserts that his boasting over his disobedient children is noticed and that this will be to their advantage on the day of judgement.” On the day of the Lord Jesus, i.e. Judgement Day, Paul will boast of his Corinthian spiritual offspring and that will win them a favorable judgement from Christ. Paul’s pride in his spiritual children will overcome any doubts the Lord has about their suitability for his Kingdom.

Paul cuts at the root of the envy which his speech might occasion by making the Corinthians sharers and partners in the glory of his good works.

St. John Chrysostom (d. AD 407

But the apostle also says that he is not simply covering over their misbehavior with false pride. They share in his ministry by supporting him, listening to him, responding to him, correcting themselves based on his instructions. No one should be jealous that he is saying good things about them just because he wants to put on a face of false bravado.

They have understood his teaching in the past and he is confident they will understand his teaching now. True understanding involves a real response. The Corinthians didn’t just say, “Yes, yes” and then ignore what St. Paul had said. They might have disagreed or argued with him at first but when they understood his points, they responded by putting their understanding into action.

This correlation of understanding and action is at the heart of what St. Benedict wrote in his six-century Rule. A true monk — i.e. a real Christian — listens to his teacher and that listening involves action in response. “Listening” is not a passive activity; sound waves don’t enter your ears and then get forgotten. Listening is a very active process, in which the monk — or lay Christian in the world — hears the teaching, chews on it, mulls it over, and then integrates the teaching into his/her behavior.

Many times in the Psalms this point is also made: to hear is to act (Ps. 40, 45, 85). Jesus makes the same point: he listens to the Father and his listening results in his obedient action. Truly listening, the speaker and the hearer each want the same thing, they have one will. Authentic fellowship, i.e. communion, results.