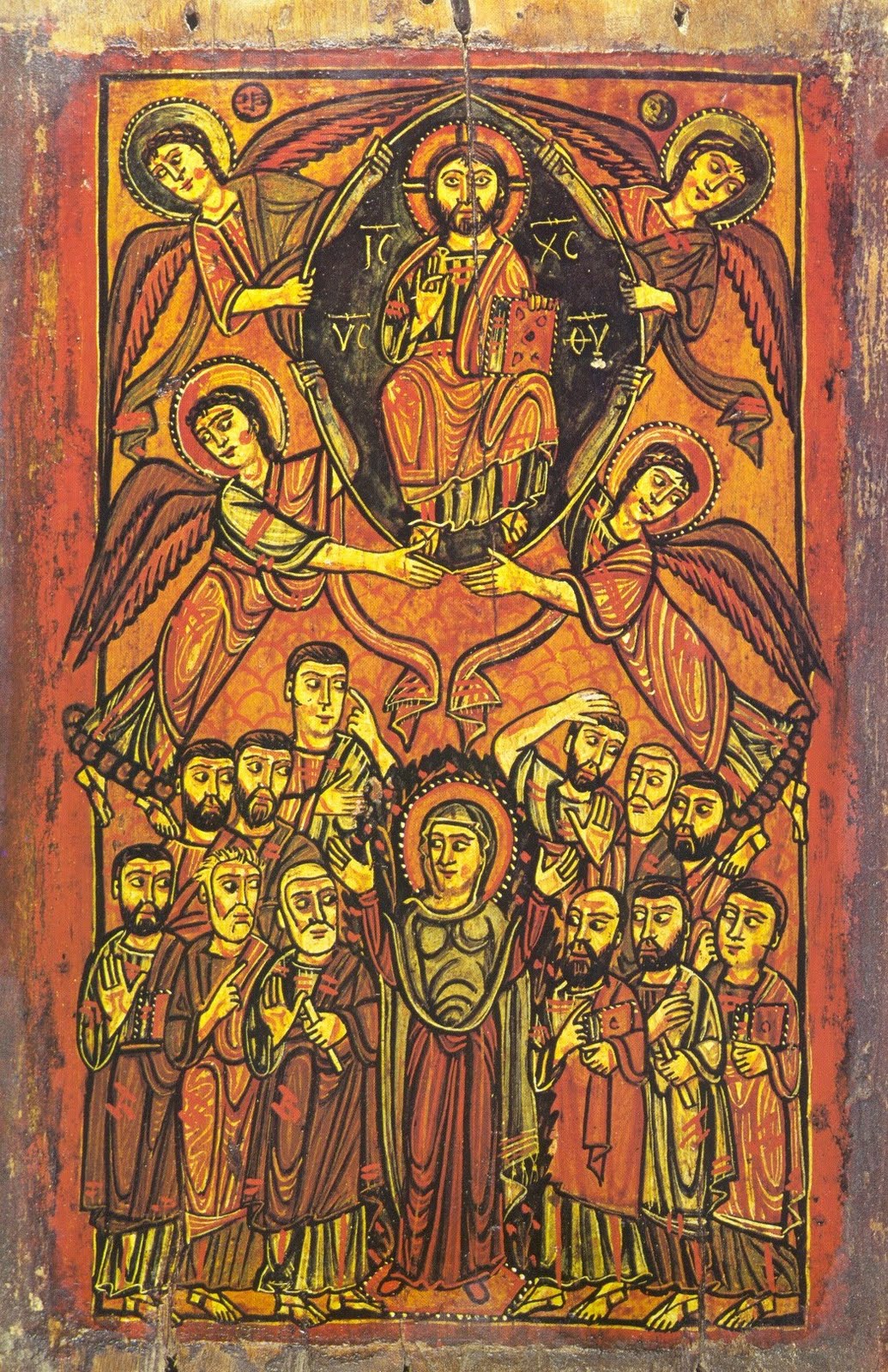

Icon of Ascension Day, showing Christ enthroned in glory above with the apostles and Mother of God below. The Ascension icon can also be viewed as an image of Christ coming at the end of time to judge the world.

Ascension Day is an important day in the church calendar and in the rural, farming calendar as well. It is also an important day among the Pennsylvania Dutch (The Pennsylvania Dutch, commonly called “Amish,” maintained numerous religious affiliations, with the greatest number being Lutheran or Reformed, but many Anabaptists as well.)

Among the Pennsylvania Dutch sewing on Ascension Day is strictly forbidden. Other work of many kind, especially farm work, is also eschewed. Lightning has been reportedly striking those sewing or working on Ascension Day. Rain water from an Ascension Day storm is thought to cure eye and vision problems if used to wash the eyes with. Not only does rain fall and thunder rumble down from the heavens above, these are generally associated with Thursdays; as Ascension is always a Thursday, making the 40th day after Easter, thunder came to be associated with Ascension as well. (The Pennsylvania Dutch name for “Thursday” is a variant of the word for “thunder.”)

Reportedly in Bulgaria the grandmother of each family will go to the cemetery on Ascension Eve and lays face down atop the grave of the most recently deceased family member. She prays there a while for that family member and for all the deceased ancestors, following which she nicks her left breast (above the heart) and lets a few drops of blood fall onto the grace to feed the ghost(s) and bring blessing to the deceased for another year. Happy ancestors will bring fertility and good luck to the family, their farms and farm animals until the next Ascension Day.

For more, see the excerpts from Eastertide in Pennsylvania: A Folk-Cultural Study.