Twice the Christian Church has been overwhelmed by controversy about whether God can be present in or act through material things.

The first time was in the Christian East, when the iconoclasts insisted that icons should be destroyed, not merely not venerated. You can read about all the dates and details in a book. The important thing to know is that the iconoclasts systematically leveled churches that were adorned with icons and dissolved monasteries, confiscating monastic property because the monks led the resistance against the iconoclastic efforts to wipe out icons. Finally, in AD 843, the icons were restored to the great cathedral of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople and a massive procession was held. People carried icons large and small through the streets of the imperial capital to celebrate the vindication of the icons, the triumph of Orthodoxy as it is still referred to, and every year on the first Sunday of Lent—the anniversary of that massive procession—each parish of the Greek and Russian Churches celebrates the Triumph of Orthodoxy again, processing with icons at least around the aisles of the church if not through the streets of the city.

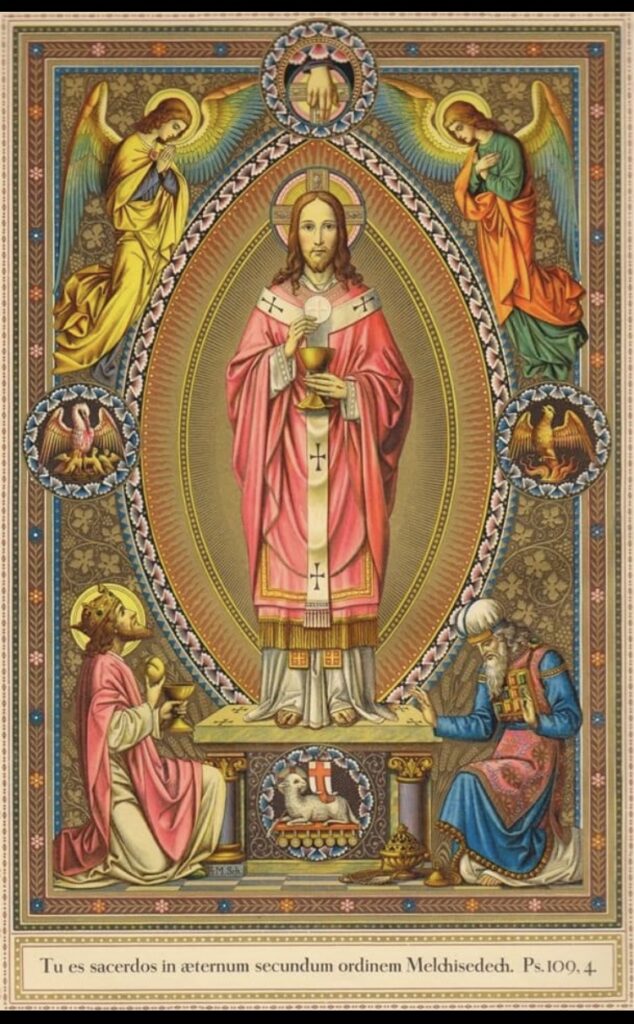

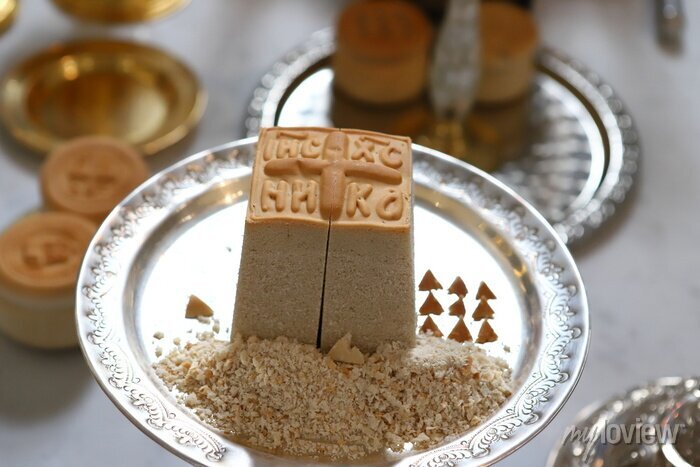

The second time the Christian Church was torn apart by the controversy about whether God can be present in or at through material things was in the Christian West. You can read about the details of these Eucharistic controversies in books as well; the important thing being that these continued on and off for nearly 400 years. The Western Church was torn by riots between those who did vs. those who did not believe that Christ is truly present in the Eucharist. It was not until AD 1215 that the question was settled that yes, indeed, Christ IS truly present in the Eucharist and in 1246 a nun, Juliana, organized a procession with the Blessed Sacrament through the streets of a city in Belgium to celebrate Christ’s presence in the Eucharistic bread.

In both cases—the iconoclastic controversy in the East and the eucharistic controversy in the West—the dispute was about whether God can be truly present in material objects and whether it is appropriate to offer incense, prayers, and proskynesis (prostrations and genuflections). In both cases, the Church acknowledged that God can be present in material things because God himself was made flesh in the womb of the great Mother of God, Mary most holy and—in both cases—that incense, prayers, and genuflections are appropriate recognition of the presence of God. And in both cases people began to hold processions through the streets with the material objects that were at the heart of the controversies… icons in the east, the Eucharist in the west.

We hold processions through the streets with icons or the Eucharist to celebrate God’s blessing on the world in general and on our neighborhood in particular. We acclaim the Eucharist and offer our worship—music, incense, singing, kneeling and genuflecting—to recognize and celebrate God’s presence with us. God is with us and what else can we do but sing like the angels and bow down with our faces to the ground?

We should-we must carry the Eucharist in procession to celebrate that God is with us. Even here. Even now. But we should-we must examine ourselves, turning ever more completely toward the God who gives himself for us. Even here. Even now. And we should-we must forgive and embrace the neighbor that we find beside us—whether we like them or not—if we hope to experience the NOW of eternity as abundant, inexpressible joy. Even here. Even now.

My most popular post was also about Corpus Christi—almost 1,000 people viewed it on the day it was published! Read it here.