Perchta or Berchta (English: Bertha), also commonly known as Percht and other variations, was once known as a goddess in Southern Germanic paganism in the Alpine countries. Her name means “the bright one” and is probably related to the name Berchtentag, meaning the feast of the Epiphany.

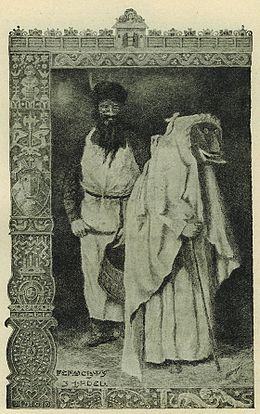

Perchta is often identified as stemming from the same Germanic goddess as Holda and other female figures of German folklore, such as Frija-Frigg. According to Jacob Grimm, Perchta is Holda’s southern cousin or equivalent, as they both share the role of “guardian of the beasts” and appear during the Twelve Days of Christmas when they oversee spinning. In some descriptions, Perchta has two forms; she may appear either as beautiful and white as snow like her name, or elderly and haggard.

Grimm says Perchta or Berchta was known “precisely in those Upper German regions where Holda leaves off, in Swabia, in Alsace, in Switzerland, in Bavaria and Austria.” In Bavaria and German Bohemia, Perchta was often represented by St. Lucia.

Perchta had many different names depending on the era and region: Grimm listed the names Perahta and Berchte as the main names (in his heading), followed by Berchta and Frau Berchta in Old High German, as well as Behrta and Frau Perchta. In Baden, Swabia, Switzerland and Slovenian regions, she was often called Frau Faste (the lady of the Ember days) or Pehta or ‘Kvaternica’, in Slovene. Elsewhere she was known as Posterli, Quatemberca and Fronfastenweiber.

In southern Austria, in Carinthia among the Slovenes, a male form of Perchta was known as Quantembermann, in German, or Kvaternik, in Slovene (the man of the four Ember days). Grimm thought that her male counterpart or equivalent is Berchtold.

According to Jacob Grimm (1835), Perchta was spoken of in Old High German in the 10th century as Frau Berchta and thought to be a white-robed female spirit. She was known as a goddess who oversaw spinning and weaving, like myths of Holda in Continental German regions. He believes she was the feminine equivalent of Berchtold, and she was sometimes the leader of the Wild Hunt.

In many old descriptions, Bertha had one large foot, sometimes called a goose foot or swan foot. Grimm thought the strange foot symbolizes she may be a higher being who could shapeshift to animal form.[6] He noticed Bertha with a strange foot exist in many languages (German “Berhte mit dem fuoze”, French “Berthe au grand pied”, Latin “Berhta cum magno pede”): “It is apparently a swan-maiden’s foot, which as a mark of her higher nature she cannot lay aside…and at the same time the spinning-woman’s splayfoot that worked the treadle”.

Bertha is reportedly angered if on her feast day, the traditional meal of fish and gruel is forgotten, and will slit people’s bellies open and stuff them with straw if they eat something else that night.

In the folklore of Bavaria and Austria, Perchta was said to roam the countryside at midwinter, and to enter homes between the twelve days between Christmas and Epiphany (especially on the Twelfth Night). She would know whether the children and young servants of the household had behaved well and worked hard all year. If they had, they might find a small silver coin next day, in a shoe or pail. If they had not, she would slit their bellies open, remove stomach and guts, and stuff the hole with straw and pebbles. She was particularly concerned to see that girls had spun the whole of their allotted portion of flax or wool during the year.

Perchta was at first a benevolent spirit. In Germanic paganism, Perchta had the rank of a minor deity. That changed to an enchanted creature (spirit or elf) in Old High German – such as Grimm describes – but she was given a more malevolent character (sorceress or witch) in later ages.

The cult of Perchta was condemned in Bavaria by the Thesaurus pauperum (1468). It requested of its followers to leave food and drink for Fraw Percht and her followers, in exchange of wealth and abundance. The same practice was condemned by Thomas Ebendorfer von Haselbach in De decem praeceptis (1439).

Later canonical and church documents characterized Perchta as synonymous with other leading female spirits: Holda, Diana, Herodias, Richella and Abundia.