So, concerning food that is offered to idols. We know that in the world an idol is nothing and there is no God but one…. But food will not put us in the presence of God. We are not inferior if we do not eat nor are we superior if we do eat. (1 Cor. 8:4, 8)

The parish in Corinth was torn apart by several disputes, one of which involved what was or was not legitimate to eat. It was meat that had been sacrificed to idols was the problem. The obvious question is, “Then why not just go buy meat from the kosher butcher?” No problem with idols then. Problem solved.

There was a large Jewish community in Corinth with plenty of kosher butchers. I could spend 20 minutes–or several hundred words–talking or writing about how the animosity between the Jewish and the Christian communities was ready to boil over at the least provocation. Christian patronage of kosher butchers was simply not possible. Tensions between the two communities were just too high.

The Christian neighbors that needed to experience God’s peace and harmony in Corinth were more than just two theological factions or two groups that wouldn’t eat together or speak to each other at coffee hour. The labels of “weak” and “strong” throughout the epistles are code words for ethnic identity and social status. The weak were the Jewish believers, the socially disadvantaged, those on the periphery of the culture, the people who could be expelled from town because the powers-that-be don’t want to be bothered with them—just as the Jews had been expelled from Rome several times already. (Many of the Jews in Corinth being, in fact, refugees who had settled there after the most recent expulsion from the great capital, only a few years before St. Paul came preaching there.)

The strong were the Gentile believers, the socially powerful and important, the people who would probably think that it might actually be a good idea to expel the “weak” from town if they got too troublesome or demanding.

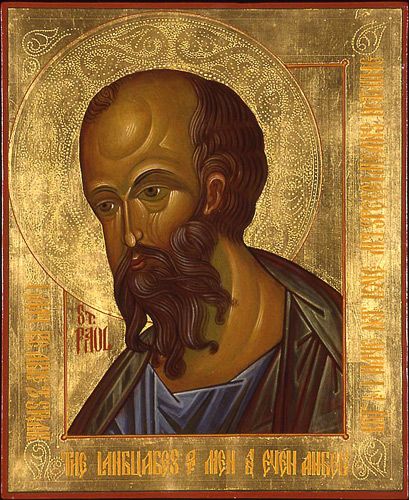

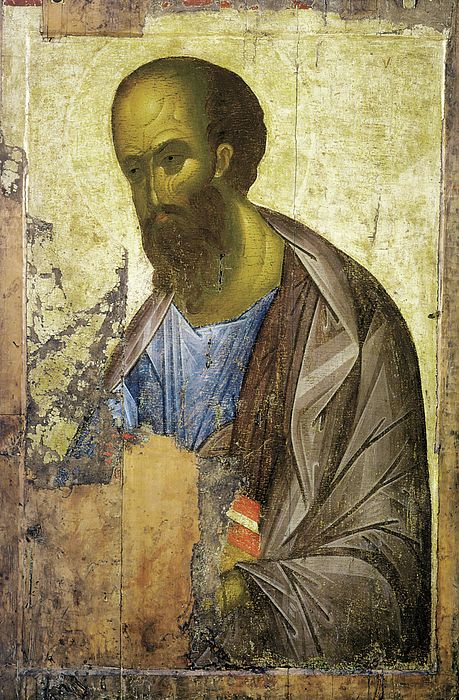

St. Paul declared that he would give up meat forever—that he would fast as the Prophet Daniel had fasted in Babylon because there was no kosher meat available—to maintain the harmony of the Christian community. St. Paul said that anyone who joined him in that fast, joined him in maintaining that harmony would also be maintaining the harmony not only of the community but the harmony of their personal relationship with God. The fast established and maintained the love and reconciliation between members of the congregation. The fast—like the holy kiss—was an expression of love for both God and neighbor.