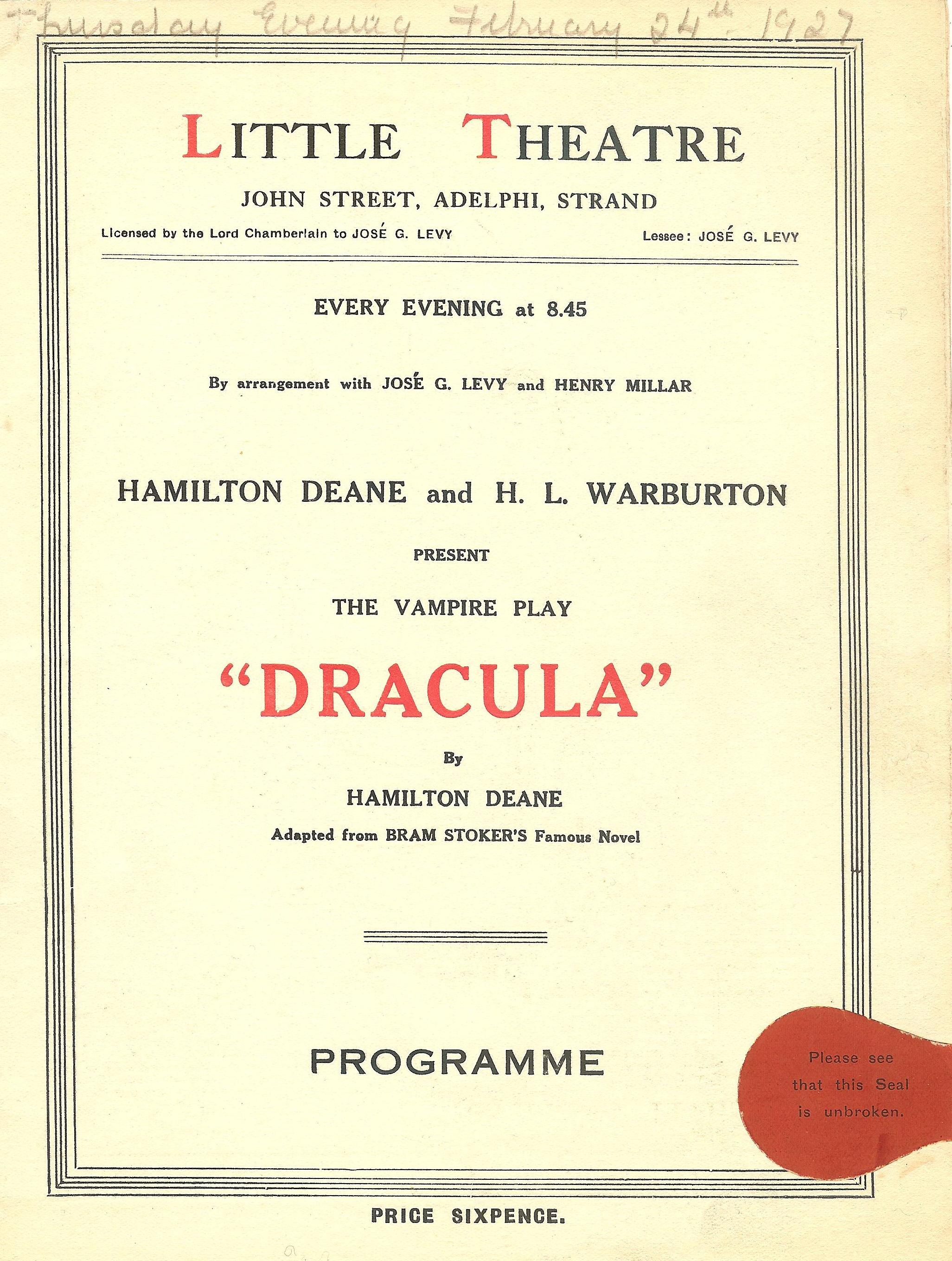

The play Dracula opened in New York’s Schubert Theatre on September 19, 1927. Originally a 1924 stage play adapted by Hamilton Deane from the novel of the same name by Bram Stoker, it was substantially revised by John L. Balderston in 1927. It was the first adaptation of the novel authorised by Stoker’s widow, and has influenced many subsequent adaptations.

In 1927 the play was brought to Broadway by Horace Liveright, who hired John L. Balderston to revise the script for American audiences. The American production starred Bela Lugosi in his first major English-speaking role, with Edward Van Sloan as Van Helsing; both actors reprised their roles in the 1931 film version, which drew on the Deane-Balderston play.

In addition to radically compressing the plot, the 1927 rewrite by Balderston, reduced the number of significant characters, combining Lucy Westenra and Mina Murray into a single character, making John Seward this Lucy’s father, and disposing of Quincey Morris and Arthur Holmwood. In Dean’s original version Quincey was changed to a female to provide work in the play for more actresses.

The play was revived in 1977, in a production featuring set and costume designs by Edward Gorey and starring Frank Langella as Dracula. The production won Tony Awards for Best Revival and Best Costume Design, and was nominated for Best Scenic Design and Best Leading Actor in a Play (Langella). Langella, like Lugosi, went on to reprise the role in the 1979 film version. Subsequent actors in the title role for the Broadway revival included David Dukes, Raul Julia and Jean LeClerc, while the London production starred Terence Stamp and American touring companies starred Martin Landau and Jeremy Brett.

(Related to the theatrical opening of Dracula, the popular television series The Addams Family debuted on September 18, 1964 and Romania issued a stamp depicting Vlad Dracul in honor of the 500th anniversary of the founding of Bucharest on September 20, 1959.)