(Dura Europas Synagogue fresco in the National Museum of Syria, Damascus)

“Son of man, can these bones live?” (Ezekiel 37)

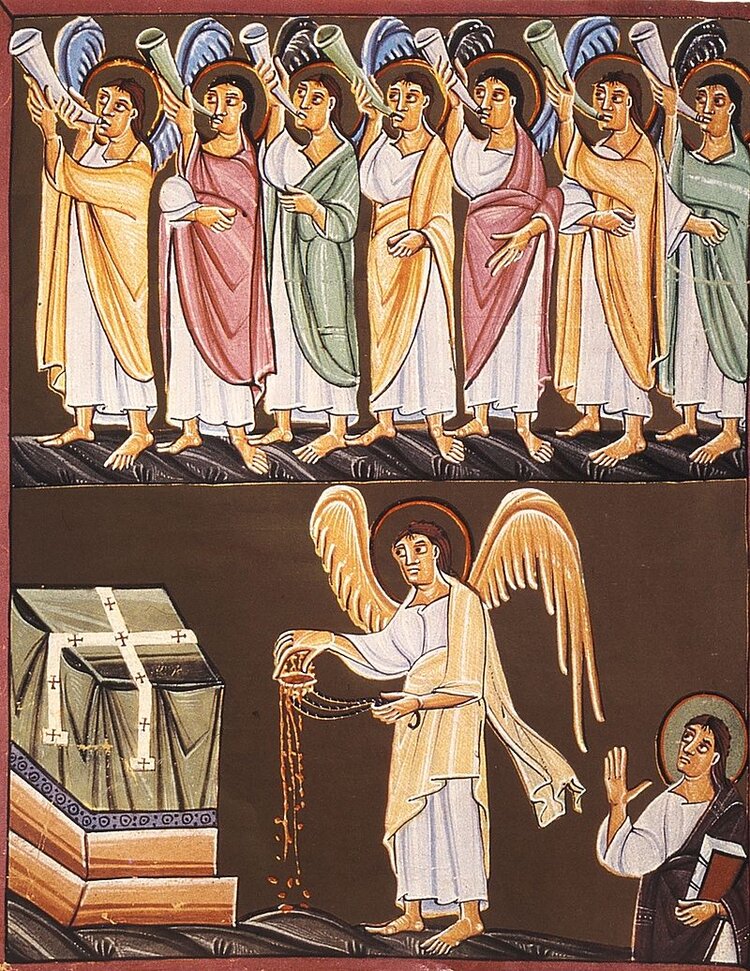

Ezekiel heard the dry bones rattle, saw them come together to form skeletons, saw the sinews and tendons grow and stretch. He saw the flesh that spread to cover them. And then he prophesied to the wind and called it to come, to fill the lungs of the dead. He saw the dead raised, the People of God restored, reconstituted, made whole. More than simple resuscitation—which only delayed death—he saw the dead resurrected. If they were resurrected, never to die again, that meant that Death itself was dead.

St. Ambrose of Milan—and most contemporary Biblical scholars as well, but my money is always with St. Ambrose—understood Ezekiel’s vision of dry bones (which occurred around 600 BC, just after the People of Israel had been taken to Babylon in exile) to mean two things: one, that Israel would be restored to their homeland. All the people who felt lost, hopeless would be revived and brought home, to where they belonged. It was a promise to the People as a whole, that although they were as good as dead in Babylon, God would eventually –on his own timetable—bring them home and give them life again in the Promised Land.

Secondly, the resurrection of the dry bones, says St. Ambrose, is also about the Resurrection of us all—each and every one of us—that will occur at the End of Days. (Many Jewish teachers had also come to understand the dry bones in this way, about 100 years before Christ.) Israel restored and the human race raised. Not resuscitated. Resurrected.

And we do not have to wait for the End of Days to experience resurrection and come home. Because Death is already dead and is already losing its power. The dead are being raised every day. “But Death is not dead yet and the dead are not being raised every day,” reasonable people pointed out to St. Ambrose. But death is dead. Just as a farmer catches a chicken and cuts off its head, only to have the corpse get up and run around the farmyard, spouting blood and making a mess and scaring the kids before it finally collapses, Christ cut the head off Death when he who is Life itself died. Death—like that chicken—can still run around and make a mess and scare people but it is already dead and it will finally collapse altogether—just like that already dead chicken—when Christ comes again in glory.

How do we experience Resurrection in advance? The dead are raised and come home every time someone is baptized. The dead are raised and come home every time we approach the altar to receive the Body of Christ—bread as dead and dry as those bones Ezekiel saw but which becomes the living and life-giving Body of Christ. The dead are raised and come home every time we actively disconnect from the things and behaviors which we use to hide from God and ourselves and our neighbors, the things and behaviors that tie us down to the fallen aspect of the world.

To live in Babylon is to live in the cemetery which is the fallen world and Jesus famously healed the possessed and destitute who lived in the cemeteries. But using Ezekiel’s voice, God promises Israel that he would deliver them from Babylon and bring them into the Promised Land; in Psalm 116, we sing, “I will walk in the presence of the Lord in the land of the living.” We understand the land of the living is the Promised Land. The living. Those raised from the dead. In a famous Byzantine church mosaic, we see Christ Himself identified as “the land of the living.” Because the land of the living is Christ himself, we see the land of the living anywhere Christ is—Heaven. The Church.