“Do not cook a young goat in its mother’s milk.” (Exodus 23:19)

I remember as an undergraduate that someone read this verse and gasped, “Who would boil a kid in its mother’s milk!?” They were aghast at such an idea and it took several minutes for them to understand this the “kid” in question was a baby goat, not a human child.

Even so, few people would cook goat in milk nowadays. But no one makes rules about things that don’t happen. So we can deduce that several non-Israelite cultures in the Middle East evidently did cook goat in milk—a kind of cream-of-goat soup or a stew with a splash of milk in it—and the point of this command is that the Hebrews should not cook in the same ways as their neighbors.

The Hebrews already understood that they should not eat meat with “the life” (blood) still in it. Now they are told not to cook meat with milk. Is there a connection?

In the ancient and medieval worlds—really, until the early 1700s—milk and semen were thought to be blood that various organs (breasts and testes) had heated until it became warm and frothy. Blood, milk, and semen were all the same bodily fluid at different temperatures. So the command not to cook with milk is equivalent to being told not to eat meat with blood still in it.

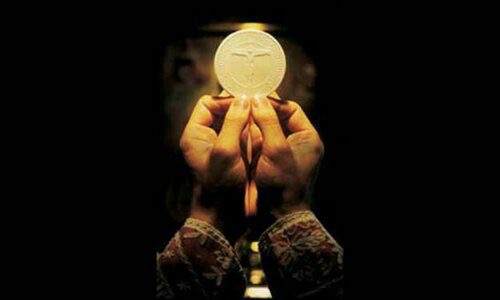

Because of this identification of blood/milk, preachers have identified the Blood of Christ in Holy Communion with the milk Mother Church suckles her children—the Faithful—with. (In the second-third century, newly baptized people would receive the Precious Blood from one chalice and warm milk with honey from another chalice because they had been brought in to the Church, the true Promised Land that flows with milk and honey.) As Christ identified himself with a mother hen who gathers her chicks beneath her wings to protect them, his Blood is also the milk that sustains the newborn Christian who is newly baptized.

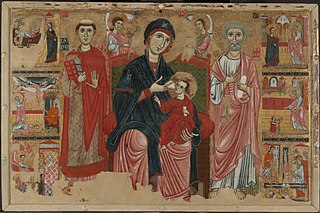

Images of the Blessed Virgin nursing the Christ Child is a Eucharistic image. She nurtured her Child with her milk, which is her blood. That milk/blood then becomes Christ’s own body/blood as a child. As he grows, that body/blood grow and mature and he then gives us his Body/Blood in Holy Communion. Everything human about Christ was given to him by his mother; we participate in his family connections when we participate in him. Body/Blood are fundamental to our humanity and sharing his, we share in everyone who also shares in him. (Read more about the Nursing Madonna here.)

Most Christians still refused to eat meat with blood in it until the 1600-1700s. Nowadays few people cook goat with milk but that’s because cuisine habits have changed, not because milk is still identified as a variation of blood. We forget how differently our Christian ancestors lived and what they took for granted; what do we think is self-evident today that will surprise Christians in three hundred years?