The first angel blew his trumpet; there came hail… cast upon the earth…. The third angel blew his trumpet and a great star fell from the sky…. The name of the star was Wormwood. (Apocalypse 8:7, 10-11)

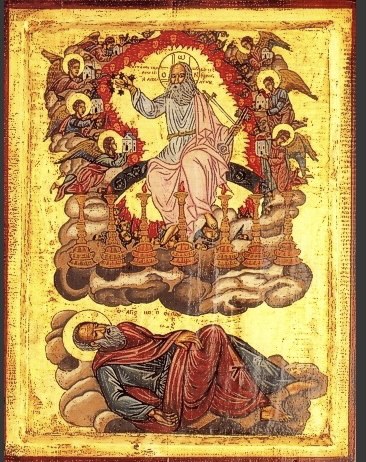

The angels begin to blow their seven trumpets and unleash a series of destructive judgements: hail with fire, a flaming mountain thrown into the sea, a falling star. Repeatedly, a third of everything is destroyed: a third of the earth is burnt up, a third of the trees are burnt up, a third of the sea is turned to blood, a third of the sea creatures die, a third of the sun-moon-stars are wiped out, a third of the ships are destroyed (see illustration above). This repetition of the destruction of one-third of everything suggests to many Early Church readers that one-third of the angels rebelled against God and became the demons of hell.

The destructive plagues released by the trumpet blasts mimic the plagues that God sent to destroy Egypt in the book of Exodus. In both cases, creation is undone and refashioned. Many of the prophets in the Old Testament describe similar plague-judgements that God will unleash at the End of Days: the sun and moon and stars will go dark, the sea will be consumed by fire, darkness will envelop the earth. Jeremiah describes a mountain that will be reduced to a burning, smoldering ruin and 1 Enoch describes 7 stars that are like 7 fiery mountains. These are not the acts of a vindictive God; these are the descriptions of what happens when creation rises up in rebellion and goes-against-the-stream that is cooperation (synergy) with God.

One of the most interesting images of judgement-destruction is the star called Wormwood. This name, which in Slavonic is Chernobyl, was often mentioned by evangelical Christians when the Chernobyl nuclear accident happened. It was popular to muse in the United States if the nuclear accident was the great portent of the End described in the Apocalypse; timelines for the coming judgement were eagerly discussed.

Wormwood is a plant with a bitter taste and is a metaphor for divine judgement (Jeremiah, Lamentations, Amos, Proverbs). This plague is the reverse of the miracle at Mara in the desert: there, poison water was made fresh but the star Wormwood makes fresh water poison. “Wormwood” is the perversion of justice in Amos: the blazing star that falls from the sky in the Apocalypse can be viewed as the downfall of the Devil himself, the father of lies and deception (John 8:44).