The slender spiral columns of white marble and the decoration carved along the top of the walls seem to refer to classical architecture. Pilate too, portrayed with the solemnity of a Roman emperor and crowned with a laurel wreath, evoking classical antiquity.

As in the gospel, the group of Pharisees, animated by lively gestures (again the hand with pointing finger), is depicted outside the building: the Jews avoid going inside in order not to be defiled and to be able to eat the Passover meal.

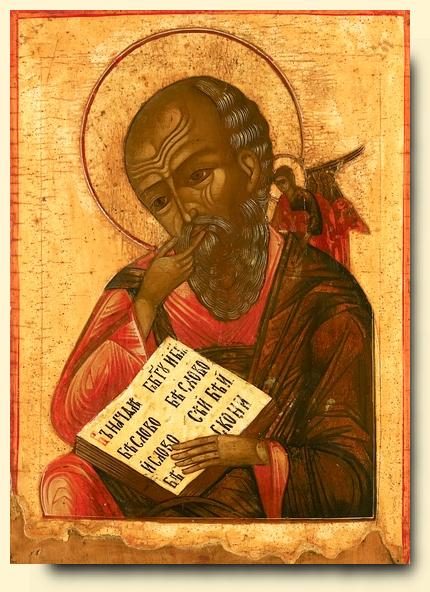

You should keep this in mind: the one who sows sparingly will also reap sparingly, but the one who sows generously will also reap generously. Let each give what has been decided in his or her heart, not reluctantly or with grumbling, for “God loves a cheerful giver” (Proverbs 22:8).

St. Paul is writing about the special collection he is making to buy food for the parish in Jerusalem that is suffering because of a famine. He is promising the people in Corinth that if they are generous to the hungry in Jerusalem, God will be generous to them … here and now, but especially on Judgement Day.

Although St. Paul was writing about money and a special collection in a specific time and place, his words apply to all times and all places whether money is involved or not. If we give our time, our attention, our energy–if we offer a shoulder to cry on or an ear to listen–God will notice that gift and if we gave that gift without grumbling, God will be generous with what he gives to us.

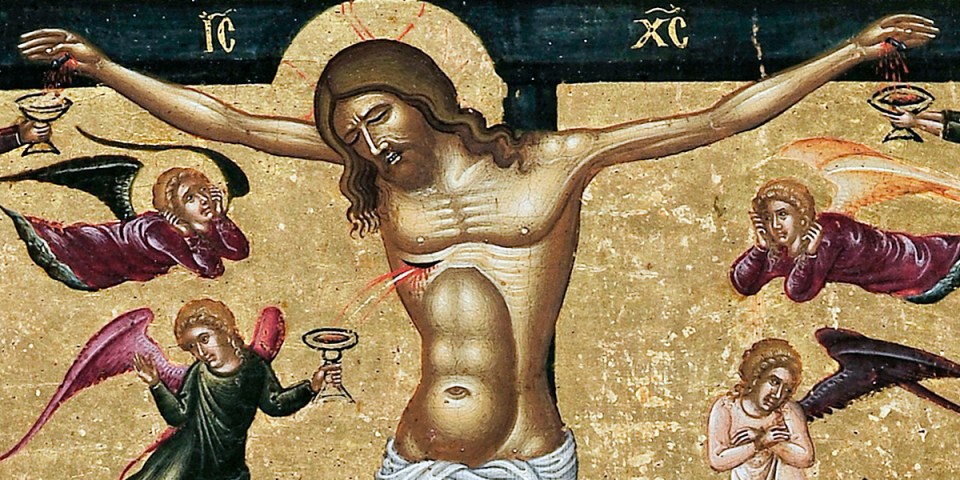

During Holy Week, the importance of cheerful giving in a variety of circumstances appears many times in the hymns, prayers, and readings. Peter refuses to give Christ the opportunity to serve when he refuses to let Christ wash his feet; then he wants too much service, offering–demanding?–that Christ wash his head and face as well. A woman washes Christ’s feet and another woman anoints his head with very expensive perfume and other people complain loudly. Pharisees grumble about the attention Christ insists they give him and his importance in the life of Israel. Romans are furious at being asked to give reconsideration to their political ideas. Apostles are afraid to give any public allegiance to Christ because they might be arrested or executed together with him.

Giving time and attention to prayer or church services this week? Doesn’t seem that much to ask now, does it? Coming to church cheerfully, without grumbling about it? Even better!

Read more about Holy Week and Judas’ complaints about a woman’s generosity in a previous post here.