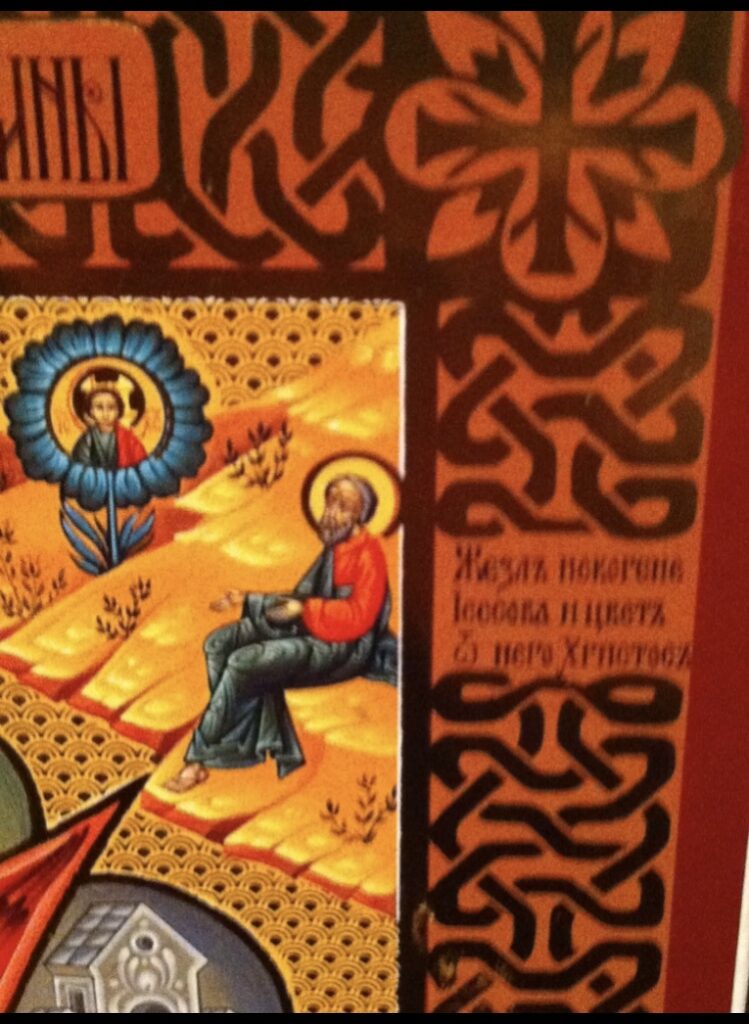

Moses was the lynchpin between God and Israel; as the Serbian proverb goes, he was the neck that turned the head (connecting the head—God—to the body, which was Israel). His encounter at the bush, as he was tending Jethro’s flocks, becomes an image of the Incarnation as the bush that burned but was not consumed is a foreshadowing of the Virgin who gave birth to God without loss of her virginity.

According to Wikipedia (so it MUST be true!), the Hebrew word in the story that is translated into English as bush is seneh(סנה) which refers in particular to brambles; seneh is a biblical dis legomenon, only appearing in two places, both of which describe the burning bush. The use of seneh may be a deliberate pun on Sinai (סיני), a feature common in Hebrew texts. (That the burning bush is a bramble bush also associates it with the bramble bush which is an important part of the story of the sacrifice of Isaac in Genesis 22.)

At the bush, Moses is commissioned to act as God’s mouthpiece, telling Pharaoh to “Let my people go” and telling the people of Israel what God wants from them. He is commissioned to build a bridge between God and the world—both the fallen world (Egypt) and the world being redeemed and healed (Israel). This role as the bridge builder between God and the world is essentially the role of a priest; one Latin word for priest is pontifex, which is literally “bridge builder.”

Even before Aaron is ordained as priest, Moses offers sacrifices to God on behalf of Israel. Moses builds the bridge between eternity and the world by his words and by sacrifice. In the Middle Ages, it was an especially meritorious act to leave money in your will to build a public bridge that did not charge a toll across a river. Building a toll free bridge was a priestly act, uniting two sides of the river as a priest unites worlds in the liturgical sacrifice and preaching. (Without a bridge, people might have to travel several miles—hours—out of their way to find a place to cross the river. A toll bridge, built by someone who wanted to make a profit on their construction investment, limited river crossing to the well-to-do; a toll free bridge was an image of Christ’s sacrifice freely available to all.)

Moses built a bridge between God and Israel. Israel, the priestly people commissioned at Mt. Sinai, built a bridge between God and the world. The Word-made-flesh, who spoke to Moses at the bush, built the ultimate bridge that brought together everything he was not with everything that he is. The Church, the Body of the Word-made-flesh, continues that ministry of bridge building.