… a synagogue leader came and knelt before him and said, “My daughter has just died. But come and put your hand on her, and she will live.” Jesus got up and went with him, and so did his disciples.

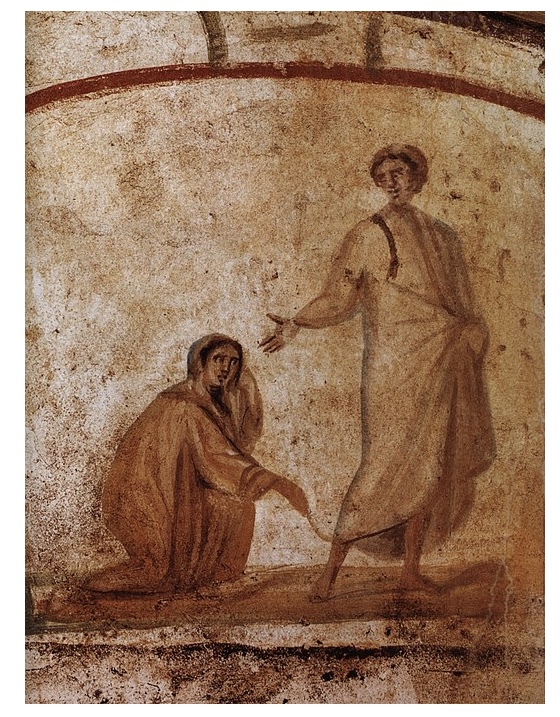

Just then a woman who had been subject to bleeding for twelve years came up behind him and touched the edge of his cloak. 21 She said to herself, “If I only touch his cloak, I will be healed.” (Matt. 9)

The woman with the 12-years hemorrhaging had been bleeding for as long as the dead 12-year old had been alive. Blood and life. 12 apostles. 12 tribes of Israel. Life vs Death. The life of the Kingdom vs fallen life in a fallen world. The episodes of the girl and the woman are short hand for the Gospel in so many ways.

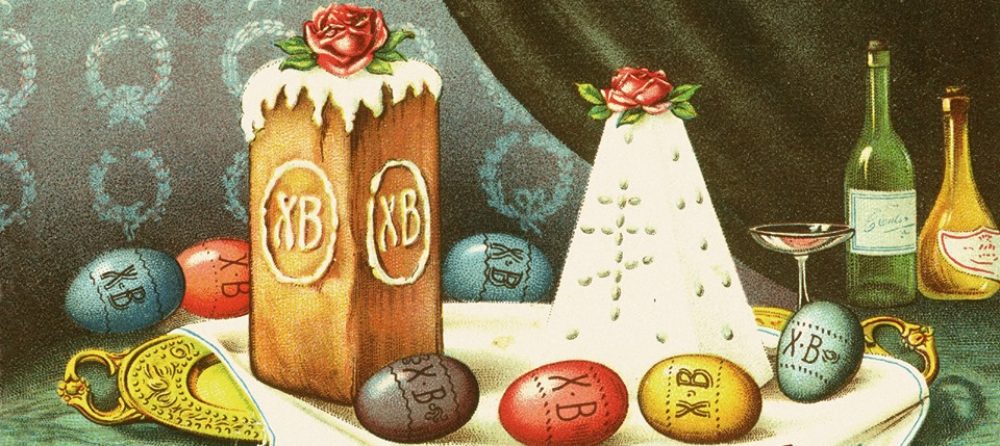

The hemorrhaging woman is frequently cited in prayers in preparation for Holy Communion. We see ourselves in her: as she dared to reach out to touch Christ’s garment, hoping to be healed, we dare to reach out to receive his body and blood, hoping to be healed as well. Healed. Raised from the dead. Healed, aka “saved.” (Both words are derived from the same root in Greek.)

We “are bold” to say Our Father before Communion. Do we realize how daring it is to reach out, making a throne with our palms to receive the King of Kings? We frequently do this pro forma, unthinkingly, out-of-habit. But if we were truly awake, would we dare?

This woman, traditionally known as Berenice, is possibly also the woman known as Veronica who is said to have wiped Christ’s face with a cloth which was then marked with the image of his face. (Veronica and Bernice are both names derived from the same Phoenician root.) Both stories—Bernice and Veronica—are about daring to reach out, daring to touch. About cloth.

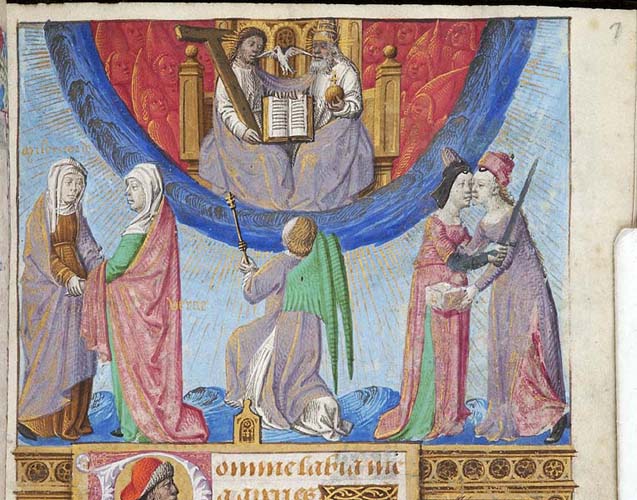

The Word of God clothes himself in human flesh. He dares to reach out towards us, inviting us to reach out to him. He dares to touch us in our grief, isolation, need. He welcomes our touch in return.