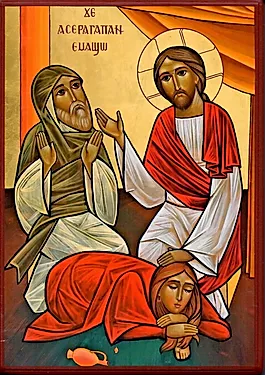

The sinful woman who anoints the feet of Jesus is commemorated by many churches during Holy Week. She anoints Jesus’ feet with very expensive perfume, wipes them with her hair, but is criticized and rebuked for “wasting” the perfume rather than spending the many on assisting the poor. Christ defends her, pointing out that the poor will always be available to be assisted but that he will not always be so available. He promises that the woman and what she did will be remembered wherever the Gospel is preached.

In some versions of the Gospel story, everyone present criticizes the woman. In other versions, Judas is the loudest or only critic. In the liturgical hymnography of Holy Week, we sing that “she loosed her hair while Judas bound himself with wrath,” i.e. that although her hair was loose–an indication of wild self-indulgence and lack of self control–it was Judas who was the one who was the one who lacked any self-control. He was tied in knots by his wrath and jealousy while she found freedom in untying her hair to wipe the feet of Christ. Appearances can deceive. In this episode, a sinful woman kisses Christ’s feet as the disciple prepares to give a kiss of betrayal. His behavior is filled with the stench of wickedness while the stench of her past is transformed by repentance.

Kurt Vonnegut once suggested that Jesus’ response might better be translated as: “Judas, don’t worry about it. There will still be plenty of poor people left long after I’m gone.” Jesus is being sarcastic, pointing out the hypocrisy of Judas and the critics of the woman who are really more interested in the money than the poor. One blog suggests that Jesus “is reminding Judas about Deuteronomy 15 and challenging his own lack of generosity. Isn’t it ironic how we can be full of zeal for compassion to the poor in the abstract, and yet be so ungenerous to those specific individuals in need that God has placed before us?”

Medieval Greek and Syrian Christian poets explore this woman’s inner emotions and thoughts in liturgical hymns for Holy Week. She has heard the words of Christ, which fill the air with sweetness just as drops of perfume fill a room with fragrance. She longs for salvation, for contact with Christ in a complex tangle of love and remorse for her past deeds. She remembers the prostitute Rahab in the Old Testament because she showed “hospitality” to the Jewish spies preparing to attack Jericho; “hospitality” is a euphemism for both her sexual services to the spies and her political betrayal of her home town that enable the Jewish attackers led by Joshua to overcome the town’s defenses. The woman in the New Testament hopes that her demonstration of love for Christ will be accepted as Rahab’s hospitality was.

But the poets contrast their own unrepentant sinfulness with the repentant but anonymous woman. They do not repent even though they know the whole Gospel story, which was more than what the woman knew. The unrepentant poets stands in for the congregation who hear the poetry sung in church: they know the Gospel story as well and do not repent either. This self-accusation of both poet and congregation is the first step toward repentance and righteousness. Because the woman was forgiven, the poet and congregation can hope for forgiveness as well–especially during the celebration of the Holy Week services.

Want to know more about Eastern Christian thought about the sinful woman who anoints Jesus’ feet and wipes them with her hair? See a contemporary Coptic Christian blog here. You can read Scenting Salvation: Ancient Christianity and the Olfactory Imagination, a fascinating account of early Christian attitudes toward scents and fragrance by Susan Ashbrook Harvey. You can also read more about the woman who anointed Christ in Liturgical Subjects: Christian Ritual, Biblical Narrative, and the Formation of the Self in Byzantium by Derek Krueger.