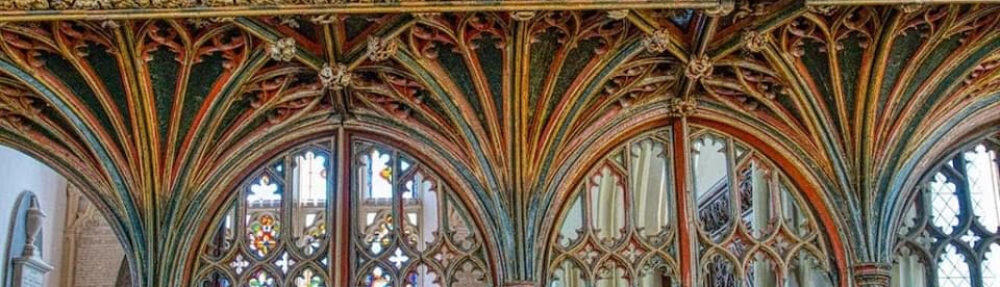

Left: Cathedral of Monreale, Sicily (built AD 1172-1267)

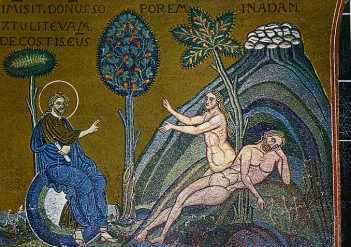

Right: Basilica of St. Mark, Venice (mosaic approx. 13th century)

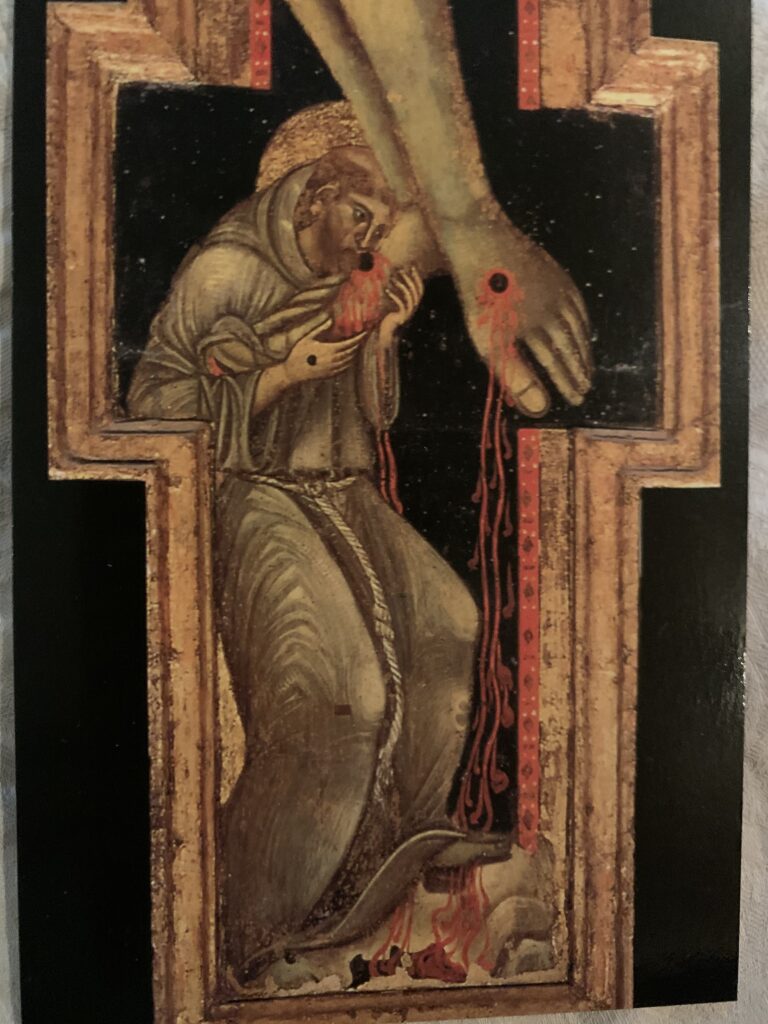

“Every eye will see him, even those who pierced him, and all peoples on earth will mourn because of him.” (Apoc. 1:7)

The first chapter of the Apocalypse is the “cover letter” that was sent to accompany each of the seven letters to the seven churches, whose contents we read in chapters 2-3. This sentence quotes Zechariah 12:10, which is also quoted in the Gospel of St. John (19:37) in connection with Christ’s side being pierced by a spear as he hung on the Cross. The prophet in the Old Testament describes how God will share the suffering of His people in exile and that those who inflict this suffering will realize–too late?–who it is that they have been really tormenting. The gospel cites this allusion to illustrate how Christ is the fulfillment of all that Israel has been hoping for. In the Apocalypse, the true identity of the letter-writer–the true author who ‘dictates’ the letter to John, to be written down–is the same Christ who hung on the Cross and was pierced.

When Christ’s side was pierced on the Cross, blood and water poured forth. (Scientists report that the “water” was most likely hydropericardium, a clear fluid that collects around the heart during intense physical trauma.) Early Christians saw the piercing of Christ’s side as the birth of the Church. Just as Eve was born from Adam’s side as he slept in Paradise, many preachers and teachers said that the Church was born from the side of Christ as he “slept” on the Cross. Methodius of Olympus, a famous second century preacher and Biblical interpreter, said that “Christ slept in the ecstasy of his Passion and the Church–his bride–was brought forth from the wound in his side just as Eve was brought forth from the wound in the side of Adam.” The Church, the Bride of Christ, is often identified as the “new Eve” just as Christ is the New Adam. (In other contexts, the Mother of God is also identified as the New Eve. Both can be the New Eve, just as the Church and the Eucharist are both the Body of Christ–just in different manner and context.)

The blood and water that poured from Christ’s side are also considered signs of baptism and the Eucharist. Read selections from a sermon by St. John Chrysostom here about those images.