The statues and cross on this altar are veiled for the two weeks of Passiontide.

In western Christian liturgical practice, the last two weeks before Easter were commonly known as “Passiontide.” The statues and crosses would be veiled. Some think this dates from a time when Lent was itself only two weeks long and that the images were therefore veiled for all of Lent. Some think that as Lent became longer–finally becoming the 40-day fast it is now–that the statues and crosses were veiled for all of Lent. Practices varied a great deal across western Europe. In some places the crosses were covered on Ash Wednesday; in others on the first Sunday of Lent. In England it was customary on the first Monday of Lent to cover up all the crucifixes, images of every kind, the reliquaries, and even the cup with the Blessed Sacrament. In other places, veils were still only used during the two weeks of Passiontide itself.

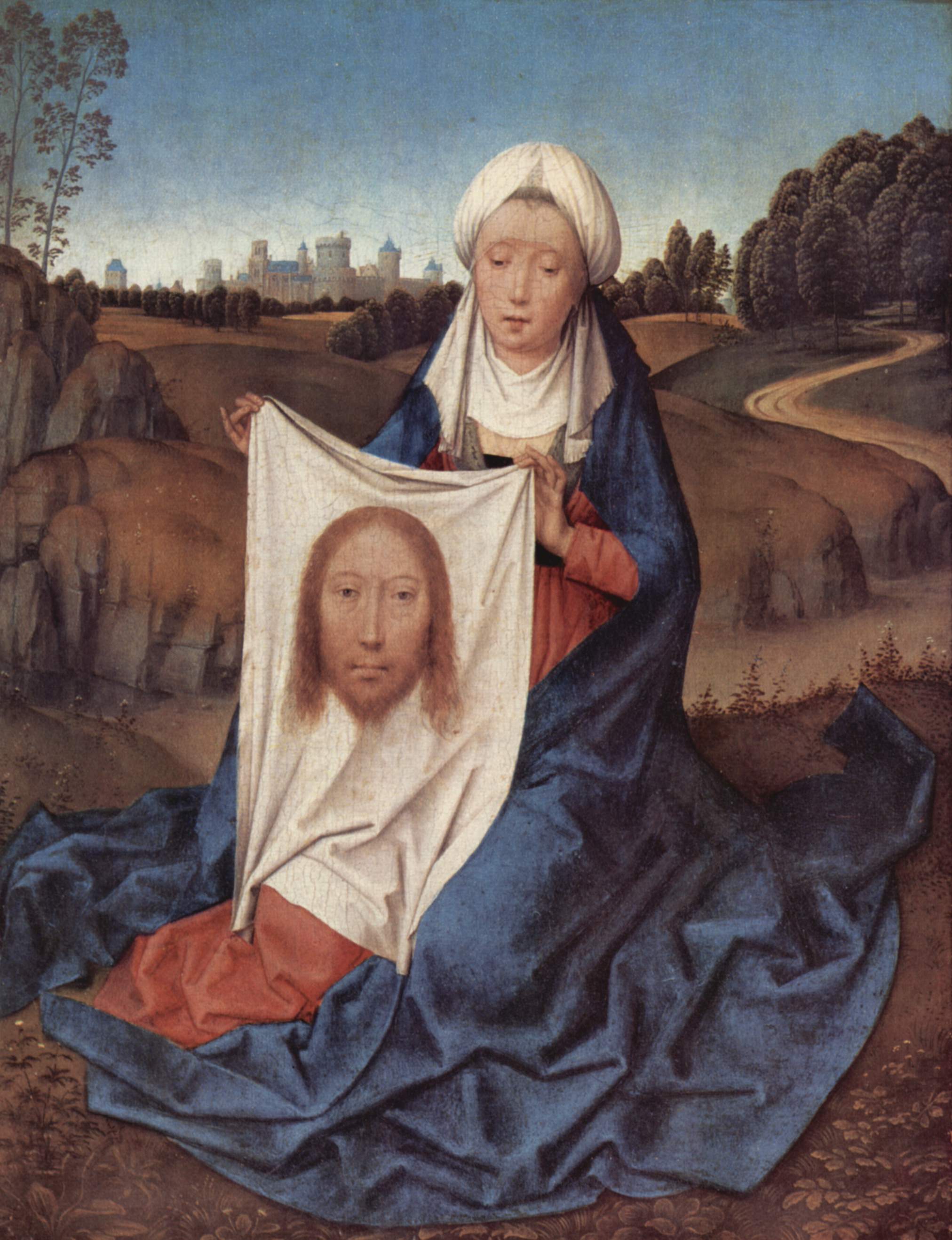

Why cover the cross and other images? Scholars suggest that at the time when veiling was introduced, the image of Christ on the Cross was still that of Christ Triumphant: his eyes are open, he is calm, and he is robed as a king or priest. He is ruling the world from the throne of the Cross, as many iturgical hymns say. The image of Christ on the Cross as the Man of Sorrows (his body twisted in agony, his eyes often closed in death, the pain and agony of Crucifixion on full display) did not become popular until much later. The veils were thus used to hide the triumphant images of Christ as the faithful were preparing to celebrate that triumph. (The saints are likewise images of Christ triumphant in the lives of believers and would therefore be covered as well during the time of preparing to celebrate Christ’s triumph over Death.) By the time the image of the Man of Sorrows on the Cross–which would be appropriate for veneration during the preparation for Easter–became popular, the veils had become too entrenched in popular custom and so the images of Christ on the Cross continue to be covered.

Even in the Orthodox world, the two weeks before Easter are distinct liturgical periods: the Week of Palms which leads up to Palm Sunday and the Passion Week which culminates in Good Friday-Holy Saturday-Pascha (Easter). But the images are not veiled in Orthodox churches.

A beautiful example of Christ Triumphant on the Cross from 13th century Pisa–currently in the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art–can be seen here.